In 2021, a remote coal town in northeastern China was forced to undergo an unprecedented financial restructuring. Its struggles since are an ominous sign for President Xi Jinping as other heavily indebted municipalities look set to follow suit.

Hegang, a city with nearly a million people near the Russian border, had debt of more than double its fiscal income when it hit the headlines almost 18 months ago. It was the first time a city administration had taken official emergency steps since the State Council unveiled rules in 2016 on how local governments, from counties to provinces, should deal with debt risks.

Hegang’s residents are now feeling the brunt of the fiscal clampdown. During a recent visit to the city, locals complained about a lack of indoor heating in freezing winter temperatures, and taxi drivers said they were being slapped with more traffic fines. Public school teachers worried about rumored job cuts, and street cleaners endured two-month delays to their salaries.

Outside the city’s largest hospital, a middle-aged orderly wearing green scrubs and a mask said her employers unilaterally changed her work contract from a government-run medical facility to a third-party vendor, reducing benefits like paid overtime for working on holidays. Her monthly wage of 1,600 yuan ($228) had been delayed by more than 10 days every month since late last year.

“I’m upset about the situation,” said the woman, who asked not to be identified in order to talk freely about her work conditions, as she pushed a wheelchair loaded with flattened cardboard boxes to an outdoor recycling point. “Everything is so expensive. I can barely get three square meals a day.”

Hegang represents just the tip of the iceberg of a local government debt problem that’s making investors increasingly nervous and that threatens to be a drag on the world’s second-largest economy for years to come. Goldman Sachs Group Inc. estimates China’s total government debt is about $23 trillion, a figure that includes the hidden borrowing of thousands of financing companies set up by provinces and cities.

While the chance of a municipal default in China is relatively low given Beijing’s implicit guarantee on the debt, the bigger worry is that local governments will have to make painful spending cuts or divert money away from growth-boosting projects to continue repaying their debt. At stake for Xi is his ambition of doubling income levels by 2035 while reducing the gap between rich and poor, which is key for social stability as he seeks to rule the Communist Party for potentially the next decade or more.

“Many cities will become like Hegang in a few years’ time,” said Houze Song, an economist at US think tank MacroPolo, noting that China’s aging and shrinking population means many cities don’t have the workforce to sustain faster economic growth and tax revenue.

“The central government may be able to keep things stable in the short term by asking banks to roll over local governments’ debt,” Song said. Without loan extensions, he added, “the reality is that over two thirds of the localities won’t be able to repay their debt on time.”

In Heilongjiang province, where Hegang is located, bond investors are already wary of the risks. The province’s outstanding seven-year bond had an average yield of 3.53%, 18.8 basis points higher than the average nationwide, ranking it among the top four most expensive.

A fiscal restructuring can be triggered in one of two ways: if interest payments on a municipality’s bonds exceed 10% of its expenditure, or if local leaders deem it’s necessary. China-based Yuekai Securities Co. estimated that as many as 17 cities had bond interest payments of more than 7% of their budgeted expenditure in 2020, meaning they are close to breaching that 10% threshold. The cities are mainly in poorer provinces like Liaoning in the northeast and Inner Mongolia up north.

Unlike a corporate debt restructuring, or a municipal bankruptcy in the US, a fiscal restructuring in China doesn’t imply creditors must take losses on what they’re owed.

Problems are evident in other cities as well. Shangqiu, a city of 7.7 million people in China’s central Henan province, made headlines recently after almost shutting down its only bus service. In Wuhan and Guangzhou, proposed cuts to pensioners’ medical benefits prompted rare street protests earlier this year. Civil servants in wealthy cities like Shanghai are reportedly having their pay slashed. In Guizhou province, officials have begged Beijing for a bailout.

Beijing has been pushing local governments to curb debt risks for years, especially the “hidden” kind — referring to debt raised by financing vehicles on behalf of municipalities, but which doesn’t show up on the balance sheets of the localities. Finance Minister Liu Kun and other officials have sought to ease public concerns by saying local government finances are overall “stable.”

“The local government debt problem is spread throughout the country,” said Jean Oi, a politics professor at Stanford University who specializes in China’s fiscal reforms. “While rich coastal areas will have more opportunities to repay their debt and more resources to draw on, less-developed places like Hegang are going to be much more limited in what they can do.”

Hegang’s Decline

Hegang had faced years of dwindling revenue from a coal industry in decline and a loss of taxpayers as the city’s population shrunk 16% in the decade through 2020. Then came the dual blows of the pandemic and a crackdown from Beijing on the property market: Officials suddenly faced a hefty bill to carry out Xi’s stringent Covid policy of mass testing and quarantines just as revenue plunged from land sales, a major source of income for local governments.

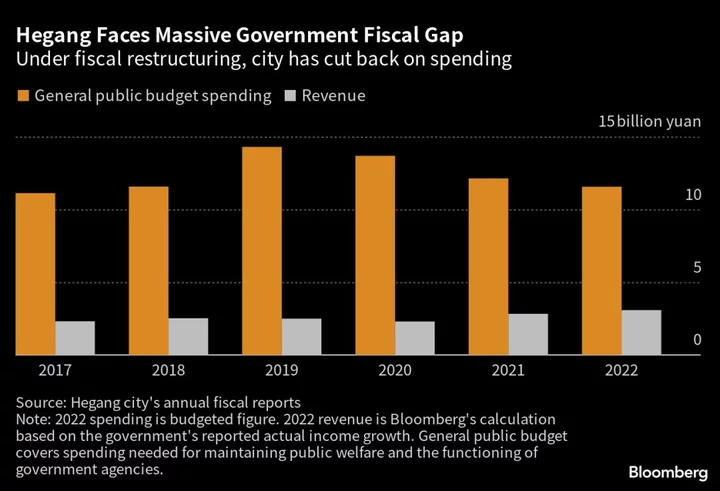

In 2020, Hegang said it was unable to pay 5.57 billion yuan worth of interest and principal on its debt because of a lack of funds. By 2021, the city’s total debt — including from off-balance sheet sources — had climbed to almost 30 billion yuan, or about 230% of its total fiscal income, according to data from official sources and media reports.

Hegang has made some progress in curbing its debt ratio to 209% by 2022, but its efforts to climb out of the fiscal hole show there’s no easy solution for Xi and his economic team.

The city’s general income, which is derived mainly from taxes, was budgeted to rise 9% in 2022, partly due to surging coal prices, which may not be repeated again. And even though fines and revenue from state asset sales were projected to rise 10%, that represents only a fraction of what Hegang needs for its budget. About half of the city’s income last year came from transfers from the provincial government, according to available official data. Hegang hasn’t published a budget for 2023.

Local officials are touting tourism and new industries like graphite mining as income generators to reduce the city’s reliance on coal. But graphite — a mineral used in everything from pencils to electric vehicle batteries — is a relatively small industry, representing only a sixth of the city’s coal sector in 2020. And while authorities are promoting Hegang as a summer holiday destination with three national forest parks and a wetland nature reserve, its remote location and winter temperatures of as low as -20C (-4F) limits its appeal as a year-long tourist attraction.

In an annual government work report delivered in March, Hegang Mayor Wang Xingzhu acknowledged that “emerging industries have not formed a strong support” to the economy while “traditional industries are in urgent need of upgrade and transformation.” Still, he struck an optimistic tone, saying the municipality has tried to reduce some of its off-balance sheet debt and “passed the peak period of debt repayment smoothly.”

One potential draw for Hegang is cheap property prices, particularly among the “lie-flat” generation of young people disillusioned by the high stress and living costs in China’s mega-cities. Hegang boasts the lowest home prices among China’s cities, a side-effect of its shrinking population coupled with excessive supply.

Diya, a 33-year-old singer and music teacher who asked to be identified by his stage name, moved to Hegang two years ago from Shanghai — a place, he said, where “even if I try my best and work 24 hours a day, I won’t be able to make enough money to become rich or own a home.” He can now afford to own three properties in the city, including his current home, a 50-square-meter third-floor walk-up apartment for 40,000 yuan — about 1% of the cost of a similarly sized place in Shanghai.

“All of my colleagues, friends and relatives laughed at me when they heard I was moving to Hegang, because that’s considered going downward to a lower place,” he said. “But Hegang is a place where you don’t need a lot of money or ambition to live well. It’s like a shelter to me.”

The city’s long-time residents are just trying to survive.

Every day, a group of aging coal workers dressed in worn-out military parkas gather from dawn at a Hegang roadside. Shovels in hand, they hope to get work for the day loading coal onto trucks and trains. One of them, Zhang, said she can earn 100 yuan, or around $15, on a good day. But more often, she’s lucky to get just 10 or 20 yuan for “exhausting” work.

“We have no subsidies, no pension,” said Zhang, 66, who asked to be identified by her surname. “I won’t retire unless I’m physically no longer able to work.”

— With reporting by Colum Murphy and Yujing Liu

--With assistance from Jing Zhao.