The unnatural steadiness of Turkey’s currency depreciation is drawing the attention of so-called carry traders, a type of investor that borrows where interest rates are low and seeks to put money to work where returns are higher.

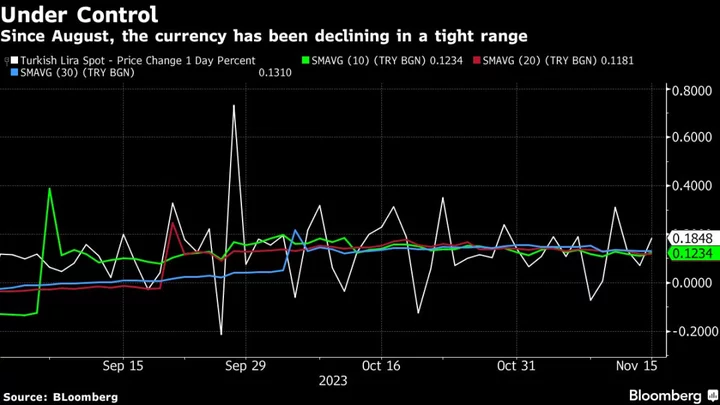

While the Turkish lira has been consistently losing value — extending its record-low level nearly every day for the past three months — its daily losses have been contained within a very narrow range, averaging just above 0.1%. As a result, one-month implied volatility, a gauge of expected price swings in the currency, sunk below 10% this month to near the lowest level this year.

That low volatility, when paired with surging yields on Turkish bonds, is creating an attractive proposition for carry trades, according to Emre Akcakmak, a senior consultant at East Capital in Dubai.

“Some investors are now dusting off their old spreadsheets,” Akcakmak said, describing the lira as displaying “crawling peg-like behavior,” a reference to a government policy of allowing only gradual shifts in a currency. Also noteworthy, he said, “is the shift in dynamics, with short-term yields now surpassing the recent changes in parity.”

By that he means that investors can now earn more from short-dated Turkish bonds than they’ll lose from currency depreciation. At the same time, cumulative monthly declines in the currency have been less than monthly inflation since August, meaning that the lira is appreciating in real terms.

While the government hasn’t said that attracting foreign capital via carry trades is part of its policy, Finance Minister Mehmet Simsek, a former investment banker, said earlier this month that ensuring real appreciation of the currency was.

Strategists at Barclays Plc expect depreciation of the lira to continue at a pace that “stabilizes the currency’s real effective exchange rate,” which accounts for inflation differentials between a nation and its main trading partners. For now though, Barclays also predicts that the lira will decline more than investors will earn, making the carry trade unattractive.

Policy U-Turns

Carry trades on Turkish assets, once a favorite of emerging-market investors, were abandoned years ago after officials in Ankara imposed a series of measures aimed at discouraging short-selling of the lira. A more market-friendly team of economic officials, led by Simsek and central bank Governor Hafize Gaye Erkan, also a former investment banker, was appointed by President Recep Tayyip Erdogan after an election in May.

They have been gradually unwinding earlier regulations in an effort to regain investors’ confidence.

But among barriers to attracting money to Turkey again are its low level of foreign-exchange reserves and sticky inflation that could force more interest-rate increases. The biggest concern among investors, however, is more than a decade of erratic policymaking and the possibility that its latest turn to orthodoxy could also be abandoned.

With volumes in the currency market low by historical standards, state-run lenders have become the main foreign-currency suppliers for Turkey’s $900 billion economy, effectively giving them power to set prices. The currency has dropped around 35% this year, the most in emerging markets after the Argentine peso.

This week, Deutsche Bank AG and BNP Paribas joined JP Morgan Chase & Co. in betting on a turnaround for the local bond market, which has seen nearly $70 billion in outflows over the past decade.