Just before the Women’s World Cup this year, Adidas AG launched a tie-in advertising campaign that shows male and female stars playing together as equals. Alessia Russo dribbles the ball past David Beckham. Lionel Messi passes to Mary Fowler. Ian Wright watches Russo tackle in amazement before Lena Oberdorf takes the ball from Leon Goretzka.

The ad, titled “play until they can’t look away,” was part of the $308 million of main tournament sponsorships collected by FIFA for the Women’s World Cup, according to GlobalData. As well as promoting its sportswear, the campaign flagged Adidas’s commitment to women in sport — a press release hailed its “ongoing support of girls and women players from the stadium to the street,” including charity donations, bespoke bra fittings for players and pitch shorts offering period protection.

Adidas — the official partner, supplier and holder of licensee rights for all FIFA events until 2030 — has stayed out of the furor caused by Luis Rubiales grabbing Jennifer Hermoso and kissing her on the lips during the team’s Aug. 20 victory celebrations, even after the Spanish football chief was ousted by the country’s federation for the kiss, with the star player disputing his claim that it was consensual.

Yet brands are less likely to wade into disputes, even behind the scenes. “If you start throwing your weight around, that is not going to go down well with other governing bodies or football associations,” which could potentially have an impact on future commercial deals, according to Richard Buchanan, a founding partner of London-based brand agency The Clearing. “It takes real guts to stand out and stand up for something.”

The German sporting giant isn’t always silent. It dropped its sponsorship of former West Ham defender Kurt Zouma after a video emerged of the player mistreating his cat. Other firms have also dropped athletes for a variety of reasons. Antoine Griezmann was dropped by Japanese video game maker Konami Group Corporation after appearing to make anti-Asian comments during a trip to Japan. Nike Inc. dropped former Manchester United Plc. forward Mason Greenwood, after the player was arrested on suspicion of domestic abuse. (Puma SE, another German sports manufacturer, declined to comment on its partnership with Antony, a Manchester United player taking a leave of absence while he faces allegations of sexual assault).

Although dropping sponsorship of individual players is far easier than entire teams, the furor around Rubiales is yet another example of the difficult question facing companies and their brands; When should sponsors — without whose support many teams wouldn’t be able to exist — wade into a controversy?

“Sponsors have a responsibility when at the negotiating table,” said Eni Aluko, a football broadcaster who played for England women’s side until 2016. “They could say how much needs to go towards campaigns for women and in turn female consumers. Brands hold a lot of power. They hold the purse to a lot of investment in the football economy.”

The expectation that companies, and the biggest sponsors in particular, take a firm stand on social issues has become more acute since the global pandemic, surveys show, with younger people especially intent on calling out injustice where ever they see it. At the same time, in an increasingly polarized world, there’s often a backlash, and calls for a boycott, as Adidas found this June when it publicly stood by its Pride 2023 swimwear adverts, which featured a male presenting model in a traditionally female swimsuit.

But companies typically closely monitor the situation to understand the shape of public opinion before speaking out. "Sponsors will consider both societal values, but also the values that they upkeep as a company. If the controversy does not align with either of these things, sponsors will be forced to speak out to protect their brand and distance themselves from the athlete," according to Joe Murgatroyd, a partner at London-based sports PR consultancy Brandnation.

But even if they publicly support DEI initiatives, firms may not feel a need to issue a response if they don’t feel pressure to speak out, Murgatroyd said, just as many haven’t in the wake of the Rubiales and Greenwood scandals.

The recent World Cup was set to be a tipping point for women’s football. It smashed records by selling nearly two million stadium tickets and ranking as the most-watched program in Australian TV history. Brands also voiced their support for national teams and players through innovative marketing campaigns, such as one launched by telecoms firm Orange, which used AI deepfake technology which seduced viewers into watching remarkable footballing moment from France’s national men’s team before revealing they were plays by the women.

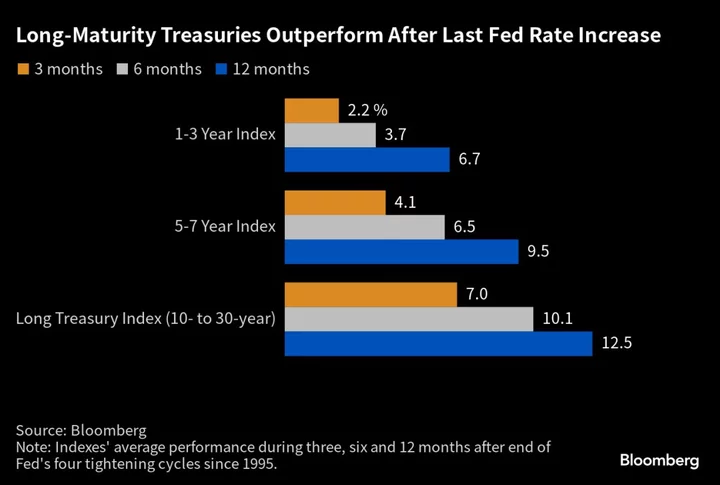

Yet sponsorship revenue still lagged the men’s tournament, bringing in an estimated $300 million, compared to the $1.7 billion created for the tournament in Qatar, according to research provided to Bloomberg by analytical firm Omdia. Accurately assessing revenue made by women’s teams is also not straightforward. Some sponsorships are done as “bundles,” meaning the deal is made with the club as a whole rather than with specific teams, so it can be hard to assign revenue to the women’s side, according to Jennifer Haskel, who helped to compile the Deloitte report.

Around a fifth of teams also faced boycotts or strikes before the games began, with squads unhappy about salaries that are far less than men’s teams, as well as working conditions, including a lack of proper training and recovery facilities. Some teams were so poorly funded that they struggled to make it to the games at all, with the mother of one Jamaican player launching a crowdfunding campaign to help towards travel costs.

And while the prize money pot has gone from $30 million for the last Women’s World Cup to $150 million for the tournament in Australia and New Zealand, it still falls short of the $440 million distributed at the men’s World Cup in Qatar.

“It’s ‘The Industrial Disputes Women’s World Cup’ for me — it has highlighted all those issues that have been under the surface,” said Professor Jean Williams, author of upcoming book Legendary Lionesses: The England Women's Football Team, 1972-2022. “Every nation is pushing for better conditions for the women.”

Still, that doesn’t mean players can rely on external parties for help. Just look at Spain where Barcelona's women's team won the UEFA Champions League in June but the minimum annual wage for a player was 16,000 euros ($17,000). Only once players went on strike did the league increase their pay — up to $21,000.

--With assistance from Siraj Datoo and Olivia Konotey-Ahulu.

Author: Helen Chandler-Wilde, David Hellier, Kwaku Gyasi and Caroline Alexander