Global bond yields got pulled higher by their Treasury peers to the greatest extent since the pandemic hit in 2020, as the US-led selloff spilled over to other markets.

Traders are bracing for 10-year US yields to top 5% for the first time since 2007 after they jumped to 4.85% this week. The correlation between Bloomberg’s gauge of global securities and an index of Treasuries has reached the highest since March 2020.

A relentless selloff in US government bonds is sparking tumult across major bond markets, as traders come to grips with the realization that interest rates are likely to remain higher for longer. Australia’s 10-year yields rose faster than their US peers over the past week despite the local central bank remaining on hold, and the volatility has also spilled over into equities.

“These moves are starting to cause worries across all asset classes,” said James Wilson, a money manager at Jamieson Coote Bonds Pty in Melbourne. “There’s a buyer’s strike at the moment and no one wants to step in front of rising yields, despite getting to quite oversold levels..”

Global bonds are now down 3.5% in 2023, while ICE’s BofA MOVE Index for Treasuries volatility jumped to the highest since May on Tuesday. The average price for bonds in the Bloomberg US Treasury Index has tumbled to 85.5 cents on the dollar, half a cent above the record low in 1981.

The yield on 30-year US bonds touched 4.98% Wednesday, the highest in 16 years. Japan’s 10-year overnight-indexed swaps jumped to 1% for the first time since January, matching the top of the central bank’s target range and underscoring speculation of a shift in monetary policy.

“Ultimately we believe in the path higher, but it’s unlikely to be linear,” said Scott Solomon, a money manager at T. Rowe Price, who last week flagged the potential for 10-year yields to test 5.5%. “There’s a bit of a back and forth between some traditional bond buyers who have been forced into a bit of a buyers’ strike when it comes to duration versus those who view the yield levels as a good long term opportunity.”

Yields on some of Asia’s emerging market bonds were dragged higher Wednesday. The Indonesian benchmark climbed to levels last seen in November.

Developing-nation bonds may be vulnerable to further declines given that investors piled in just before the rout kicked off, according to Morgan Stanley.

“Long EM duration is a pain trade for most real money investors,” analysts including Min Dai, head of Asia macro strategy, wrote in a note. Such positioning “increases the vulnerability of the market, especially if UST rates continue to march higher.”

The pain is spreading to corporate notes as well, with at least two borrowers standing down from issuing Tuesday as blue-chip yields reached a 2023 high of 6.15%. The largest speculative-grade bond ETF was hit by the biggest two-day slump this year.

“US yields at highs for the year are starting to look disruptive for other regions and sectors in global fixed income,” HSBC Holdings Plc strategist Steven Major wrote in a note to clients.

But, the very shortest end of the Treasury market still looks attractive to some. An enlarged 52-week bill sale on Tuesday attracted record demand from non-dealers, as investors locked in a yield above 5% for the next year.

Current yield levels will “suck capital away from the more risky asset classes as investors do not need to move along the risk spectrum to generate attractive returns,” Wilson from Jamieson Coote said.

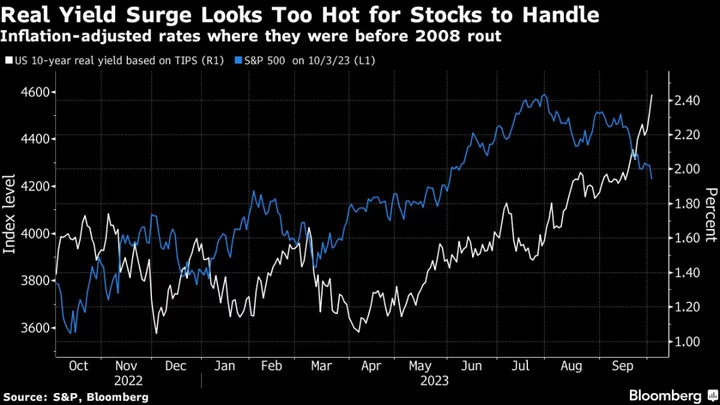

The rout has also sent so-called real yields to multiyear highs, with the 10-year US inflation-adjusted rate climbing above 2.4% to the sort of levels reached in 2007 just before US equities topped out.

“Sharp moves upwards in real yields always lead to deratings of the equity market,” said Amy Xie Patrick, head of income strategies at Pendal Group in Sydney. Cash is the best place to seek protection, she said.

(Updates yield levels and adds Morgan Stanley comment in ninth and 10th paragraphs)