The euro zone’s custodians have set a course for the biggest policy-inflicted blow since the currency was created.

The combination of higher interest rates and renewed restraint in government spending is threatening to strangle expansion and raise the risk of a nasty recession.

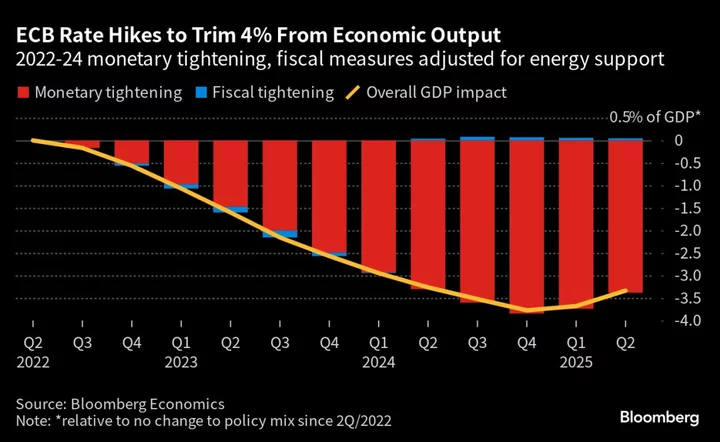

The delayed pain from hikes in borrowing costs that began last year will crescendo in 2024 to inflict a 3.8% hit on the economy, according to Bloomberg Economics analysis using its SHOK model. Depending on energy prices, the removal of support measures could amplify that closer to 5%.

Such a double punch to growth reflects the European Central Bank’s 425 basis points in tightening, along with a looming German-backed return to spending restraint. The combination of high rates, and governments with limited scope to aid expansion themselves, risks locking the euro area into a vice.

“The danger is that the resilience of the economy so far breeds complacency, and monetary tightening arrives with a lag, and a bang,” said Jamie Rush of Bloomberg Economics, who co-authored the research with Maeva Cousin. “By then, governments could be in a poor position to stabilize activity.”

While Federal Reserve staff are now anticipating a soft landing for the US, the crunch bearing down on the euro zone shown by their calculations points to dimming prospects for such an outcome there.

The impact could exceed the prior tightening cycle before the global financial crisis and rival the fallout from the sovereign debt crunch a decade ago.

Whether the economy is robust enough to sustain that squeeze without a damaging recession is the quandary facing the ECB and finance ministries, at a time when neither side of the policy mix is openly confronting that prospect.

Options markets trading suggest policymakers will blink and rapidly cut rates, but the ECB’s formal signals are for a prolonged period of higher borrowing costs.

The prospect of the economy sandwiched between that crunch and a pullback in government aid threatens a dilemma as officials attempt to combat inflation.

Having incurred criticism for a belated start to tightening, the ECB is already in the sights of politicians for the pain that rate hikes are starting to inflict.

So far, the economy has proved hardy when confronted with a record bout of tightening and the gradual withdrawal of government-financed measures provided during the energy crisis.

The euro zone skirted a winter recession and then rebounded in the second quarter, albeit with an uneven performance as Germany stagnated and Italy contracted.

But now, as ECB President Christine Lagarde acknowledged last month after opening the door to a pause in tightening, the near-term economic outlook has “deteriorated.”

By January, it will be 18 months since the first rate hike — a moment conventional economic wisdom suggests will mark the high point of its impact.

That same month, the suspension of the EU’s fiscal rules limiting debt and deficits will end after four years when governments had leeway to throw money at the economy to cushion the shocks of the pandemic and the energy crisis.

While negotiations over a new framework are still ongoing, the outcome will at least reimpose some kind of limit. Just last month, euro-zone finance ministers agreed that “gradual and realistic fiscal consolidation is warranted.”

“In the next 12 months we are going to live in a period where we have both the maximum effect of monetary tightening at the same time as a fiscal tightening,” said Gregory Claeys, a senior fellow at Brussels-based think tank Bruegel. “I’m a bit worried, to be honest.”

A key part of the debate is the extent to which rules will be flexible enough to allow governments to adapt during periods of economic strain.

That has revived stark divisions between northern and southern European countries, with a hawkish group led by Germany demanding automatic limits and others including France advocating flexibility.

“There is no point in having rules that are subject to political whim and never work in the end,” German Finance Minister Christian Lindner wrote in an op-ed in February. “There must be no special paths for individual states.”

Even without the EU’s regime shift, ballooned debt levels from the Covid era, along with higher borrowing costs and ongoing market scrutiny, could mean diminished room for action.

If an economic slump transpires, the ECB would become a focal point of political sniping, not least in the prelude to European Elections in June 2024. The central bank is independent, but attacks on its policy won’t be comfortable to endure.

“It will be increasingly difficult to defend keeping rates that high,” said ADA Economics Ltd. Chief Economist Raffaella Tenconi. “If there is no pivot, then next year is going to be brutally painful.”

Clouding the picture for central bankers is uncertainty about how rate increases will feed through to the economy. Even so, some policymakers have warned that the drag won’t ultimately be any smaller — rather, it’s just pent up.

What’s more, the squeeze of higher rates will intensify as companies continue to battle headwinds including higher energy costs, struggling real-estate sectors, and slowing consumption after the inflation surge.

“When you’re hit by a rate hike when everything is going ok, you can digest it more easily,” said Germain Simoneau, head of the finance committee at French small business federation CPME. “These hikes might be felt differently.”

Rush of Bloomberg Economics said the best scenario for 2024 is a soft landing, but the omens aren’t great.

“The danger is that higher interest rates eventually hit the economy as hard as models predict,” he said. “And governments with high debt burdens facing severe fiscal constraints are unable to perform the stabilizing role we became accustomed to.”

Read More on the Europe’s Economic Woes:

- Germany’s Economic Malaise Evokes ‘Sick Man of Europe’ Era

- ECB Rate Uncertainty Looms Over Euro Zone’s Weakening Economy

- EU Commission Sets Up Clash Over Reform of Bloc’s Debt Rules

--With assistance from Kamil Kowalcze, James Hirai and Caroline Alexander.