Intel Is in Talks to Be an Anchor Investor in Chip Designer Arm’s IPO

British chip designer Arm Ltd., backed by SoftBank Group Corp., is in talks with potential strategic investors including

2023-06-13 09:27

Oil Holds Near Three-Month Low as Demand Concerns Reverberate

Oil held near the lowest level in almost three months on persistent concerns over the demand outlook in

2023-06-13 08:47

UK Needs to Build Eight-Hour Batteries to Balance Power Grid

The UK will need batteries that last four-times longer to balance supply and demand in a system that’s

2023-06-13 07:25

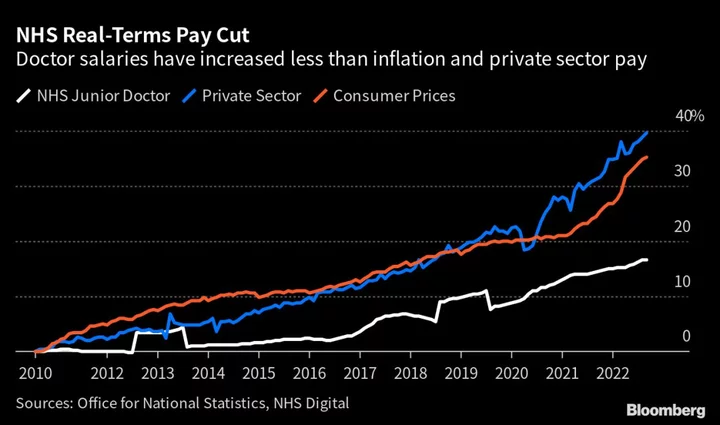

England’s Health Crisis to Deepen Amid Latest Doctors’ Strike

England’s hospitals face major disruption this week when junior doctors begin a three-day walkout in the latest row

2023-06-13 07:15

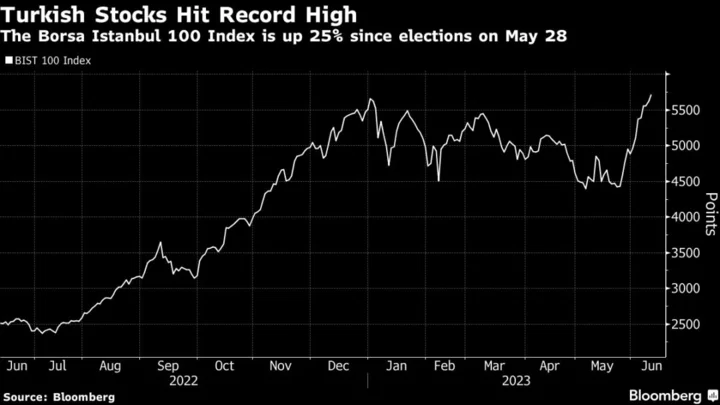

Turkish Stocks Soar to Record High on Hopes of Policy Shift

Turkish stocks surged to record highs, while the lira remained at all-time lows, as the appointment of two

2023-06-12 20:51

Panel to Discuss If There’s a Successor for Credit Suisse’s CDS

The panel that oversees the credit-default swap market, the Credit Derivatives Determinations Committees, will discuss whether there’s a

2023-06-12 20:50

British girl shot dead in France ‘by neighbour who complained about noise and cutting trees’

A pensioner arrested after a British schoolgirl was shot dead in France had allegedly been in a dispute with the neighbouring family for years. Details of the build-up to Saturday’s attack emerged following the killing of the 11-year-old - who has been named as Solenne Thornton by French authorities. Her parents were also shot during while enjoying a family barbecue in the French hamlet of Saint-Herbot. The victim’s father Adrien Thornton is in critical condition and her mother Rachel was also wounded. Solenne’s sister Celeste watched in horror as her older sibling was shot while playing on swings, before the eight-year-old ran from the scene screaming: “My sister is dead, my sister is dead.” French police launched an investigation for the murder of a child under 15, and two attempted murders. A 71-year-old Dutchman, who has not been named, is in custody along with his wife after both were arrested by firearms officers. Have you been affected by this story? If so email tara.cobham@independent.co.uk Officers from the GIGN – the Gendarme National Intervention Group – arrived to support local police during the fatal incident. “The shooter locked himself in his home after the shooting so there was a brief siege,” a source said. “After some negotiation, the suspect gave himself up without a struggle, and he was arrested, alongside his wife. He had retired to Saint-Herbot around six years ago.” Marguerite Bleuzen, Mayor of Plonévez-du-Faou, revealed there had been ‘some trouble with a neighbour dispute’ between the two families since at least 2020, while locals claimed the pensioner had previously threatened the family with a .22 rifle the same year. “That’s what the dispute three years ago was all about – police were called because he was threatening the family with his rifle,” one unnamed resident said. “The two families were always arguing, and the rifle escalated matters, but nobody ever believed that he would use it.” The weapon was a licensed hunting rifle, and no effort was made to confiscate it by the police, or council officials. The Dutchman - whose wife was said to be a “pleasant neighbour who said hello to people” - was described as “gruff and withdrawn”, regularly complaining about the family cutting down trees to make way for children’s play equipment, including swings. “He was also regularly upset about the noise the family made, even though it didn’t bother anyone else – it was mainly just kids having a nice time,” a resident said. Following an official intervention three years ago, there had been “no emergency”, but Ms Bleuzen was aware that arguments continued to simmer. “I intervened with my deputies when we were elected,” she said. “There was a problem with the land around their properties, and with noise pollution – it started from there. “I think they all had a little trouble getting on with each other.” Ms Bleuzen added: “The family was well known and liked. There is a village fête every year and they always came. “It’s incomprehensible to have shot a child. No one can understand how that could have happened.” All of the Thorntons were in the garden of their property when shots were fired at around 9pm on Saturday. They had lived in the property – a converted sawmill close to the local Catholic Church – for around five years. Mr Thornton was well known around the hamlet and surrounding countryside for helping out with DIY tasks, while Mrs Thornton was a home help. Solenne was believed to be a pupil at Jean Jaurès College, in the town of Huelgoat. Quimper prosecutor Carine Halley said: “An investigation has been opened into the murder of a minor under 15, and two attempted murders.” She said she believed the Thorntons were originally from the Manchester area. The UK Foreign Office said it aware of the shooting and “offering consulate assistance”. Read More Watchdog: Nuclear states modernize their weapons, Chinese arsenal is growing Paris street submerged by water as heavy rain hits French capital From GPS-guided bombs to electronic warfare, Russia improves its weaponry in Ukraine France shooting – latest: British girl killed during barbecue in Brittany as father fights for life British girl, 11, shot dead as she played on swings in family home in France Man accused of knife attack on four children in Annecy held on attempted murder charges

2023-06-12 20:45

Nasdaq to Purchase Adenza From Thoma Bravo for $10.5 Billion

Nasdaq Inc. agreed to buy financial-software maker Adenza from its private equity owners in the exchange operator’s biggest-ever

2023-06-12 20:26

JPMorgan’s Ultimate Survivor Caught in Crossfire of Jeffrey Epstein Feud

Mary Callahan Erdoes has watched one star executive after another climb to the highest rungs at JPMorgan Chase

2023-06-12 19:59

Ukraine-Russia war – latest: Moscow claims it repelled fresh offensives as Kyiv liberates four villages

Russia’s defence ministry said on Monday it had repelled attempted offensives by Ukrainian forces in the Donetsk and Zaporizhzhia regions and had hit targets with sea-launched high-precision missile strikes. Russia said its forces had launched a strike on Ukrainian army reserve locations using long-range precision weaponry, launched from the sea. Ukraine said on Monday its troops had recaptured a fourth village from Russian forces in a cluster of settlements in the southeast, a day after reporting the first small gains of its long-anticipated counteroffensive. Meanwhile, Ukraine’s deputy defence minister Hanna Maliar posted a photo showing soldiers hoisting the Ukrainian flag at what she said was the village of Storozheve in Donetsk, and thanked the 35th Separate Brigade of Marines for liberating it. Reuters confirmed the location of the footage. Kyiv also said on Sunday that its forces had liberated three villages - Blahodatne, Neskuchne and Makarivka. The long-expected counteroffensive was indirectly confirmed by Vladimir Putin on Friday, who said that a Ukrainian military push was underway, but had failed to breach Russian defensive lines and taken heavy casualties. Read More Mapped: Ukraine claims four villages captured in first gains of counteroffensive Ukraine's dam collapse is both a fast-moving disaster and a slow-moving ecological catastrophe Musician Travis Leake spoke up about freedom of speech in Russia with Anthony Bourdain in 2014. Now he’s been detained

2023-06-12 19:23

The story of Silvio Berlusconi and the birth of the Champions League

A version of this story was published in February 2017 Diego Maradona was one of many players struck by the strange “uniqueness” of the occasion. He wasn’t to know the half of it. Because, the last and only other time that Napoli travelled to Real Madrid - back in the 1987-88 European Cup - it involved a hugely bad-tempered game that also saw a manager call a player a “mafioso” and took place in front of no fans and in an odd silence, due to crowd trouble the previous season from Real’s infamous Ultrasurs. It was hardly the setting for such a highly anticipated match between two heavyweights, not to mention the meeting of one of the greatest players ever and the most successful European Cup club ever. All of that will likely get replayed in the build-up to Napoli’s return to the Bernabeu on Wednesday, but none of it is what really makes that 1987 match unique. This was actually the game that changed European football. AC Milan owner Silvio Berlusconi was one of many watching, but he couldn’t share in the excitement around the fixture. He was aghast at the fact that two clubs like that could meet as early as the first round of the competition, as was happening here. It was hardly the stage to waste such a highly anticipated clash, or to waste one of the sides that would be eliminated but instead should have been making the competition all the more enticing later on. Berlusconi naturally feared the same could happen to his own club, but also had wider concerns. So, he set in motion his plans for a European super league. That didn’t happen, but the idea - and the threat - directly led to the creation of the Champions League, and the super-club-dominated era we have today. It is also a situation with several levels of irony. What is only the second ever tie between Real and Napoli is now seen as a novelty in a last-16 stage that has meetings of Barcelona-PSG and Arsenal-Bayern Munich both being replayed for the fourth time in just five years, a level of repetition that has dulled some of the Champions League’s intrigue and mystique. It was exactly the intrigue and a mystique of a rarely-played fixture coming in the competition’s old opening knock-out round, however, that led to that. What’s more, this growth of the Champions League has someway cannibalised some of those who were initially so behind super league ideas - from Rangers in Scotland to Liverpool and even Milan themselves. It’s certainly difficult not to wonder what Berlusconi now thinks about Milan’s meek drift away from the glamorous competition he helped create. You don’t have to wonder what Real and Napoli thought on being drawn against each other so early in 1987, though. They were stunned. Part of the reason was that the first-time Italian champions had no European pedigree, so were unseeded. Real’s pedigree was emphasised by the fact this was their 100th European Cup match at the Bernabeu, making it all the more incongruous that it would take place in front of the stadium’s empty stands. A two-game closed-doors order was the price for crowd trouble in the previous season’s semi-final against Bayern Munich. It was probably oddly fitting that the match that would prove so transformative for the quality, glamour and scope of the competition, however, was a poor game played in front of nobody. Described by Mundo Deportivo at the time as a “cold” occasion where the players were “orphaned” on the pitch, it did heat up between the teams. Both squads probably took Maradona’s demand to “go and batter them!” a bit too literally. Many kicks and apparently punches were traded, a bag of ice was thrown at Real manager Leo Beenhakker, and Napoli’s Salvatore Bagni later claimed the Dutch coach and some of his players had called him “mafioso”. Beenhakker did apologise for that before the second leg, again citing the “unique” circumstances of the game, but from the vantage point of a 2-0 victory. The goals summed up the level of performance. Michel scored from a penalty, Fernando De Napoli was responsible for an own goal, all to the sound of silence. Returning to Spain for the first since leaving Barcelona in 1984, Maradona had been marked out of the game, and blamed Napoli’s poor display on the pressure of a first appearance in the competition. “You don’t have to exaggerate,” he said. “We did not see the true Napoli, perhaps because of the responsibility of a debut in the European Cup.” It was exactly this kind of quirk, however, that so concerned Berlusconi. He just couldn’t see the logic in the competition’s best - and most televisually lucrative - teams potentially going out because of one bad night, one stroke of bad luck. It was precisely this Berlusconi feared for Milan, as he admitted in what would prove a hugely prescient interview with World Soccer in 1991. Amid predictions about the decline of international football and how European Union regulations would completely condition the continental game, the mogul came out with the following: “The European Cup has become a historical anachronism. It is economic nonsense that a club such as Milan might be eliminated in the first round. It is not modern thinking.” Berlusconi had shown a lot of very modern thinking, particularly by football’s conservative standards, since taking over Milan in 1986. Though always a fan of the club, he saw them as one arm of his business empire. Berlusconi made little secret of his plans to use both the Rossoneri brand and his media company Mediaset together to maximise both. Having already revolutionised broadcasting in Italy with the way his innovative approach to regional stations evolved into the country’s first national private TV station in Canale 5, he had similar plans for football. Berlusconi felt the sport was utterly wasting its potential in this area, and not at all reaching a potential pay-TV audience of millions and beyond. He thought it absurd that the biggest clubs in a sport that involved so many popular stadium events were not regularly meeting in glamorously lucrative matches. Martin Schoots is now a prominent European agent representing players such as Christian Eriksen, but was then a journalist primarily covering the three Dutch stars at Milan - Marco van Basten, Ruud Gullit and Frank Rijkaard - and was always impressed with Berlusconi’s approach when they met. “He was a visionary,” Schoots says,” and very clear and convinced about what developments would come. His philosophy was that football was a spectacle.” Or, as was put by some of those close to Berlusconi, “the television spectacular world-wide” - and the potential audience for his Canale 5. Making the European Cup a super league was not quite a new idea, though. That had actually been creator Gabriel Hanot’s initial plan for the competition in 1955 in order to better reflect “rightful” champions than the nuances of knock-out football, but proved impractical with the travel and communication of the time. Liverpool had also come up with a discussion document suggesting mini-leagues in 1978, around the time they were drawn against Nottingham Forest in the first round, and that had been revived in 1984. No-one, however, had gone for it with the same force or sense of structure to it as Berlusconi. this Super League was based on merit, tradition and television - and therefore it was a league for big television markets Alex Flynn After initial moves with Real president Ramon Mendoza were rejected, the Italian businessman decided to commission a blueprint for a ‘European Television League’ in 1988. The man who ended up with that commission was Alex Fynn, then of Saatchi and Saatchi. A huge football supporter, Fynn had already given a talk at an event for the Rothman’s Football Yearbook called a ’10-point blueprint for football’, suggesting exactly a European super league. It was subsequently printed in the Times, and word got around. “A few weeks later, I got a call from the head of our Italian agency,” Fynn tells The Independent now. “He said ‘here’s the job you always wanted: design a super league for Berlusconi.’ And the reaction? “My reaction? My reaction was my head was turned, I was flattered, and I did what I thought he wanted - not necessarily what football needed. So this Super League was based on merit, tradition and television - and therefore it was a league for big television markets. I think it had a league of about 18 clubs and certainly two each from England, Italy, Spain… that was the plan.” It was a plan initially rejected by Uefa, but had still done its job. The idea was out there, as was the underlying threat of a possible breakaway and possible changes were now on the table. “He decided to publicise it and use it as a stalking horse and catalyst to support his argument,” Fynn says of Berlusconi. “I think it went further than that. When someone like Berlusconi has a plan for a breakaway European super league, even Uefa had to sit up and take notice. The underlying threat was this businessman might have the wherewithal to do what he says. In theory, breakaways aren’t tangible, because they need the sanctioning of Uefa and Fifa. So maybe he realised that and maybe all he was doing was to produce the plan to affect some sort of change that would benefit his club and his commercial business - which of course it did.” Uefa fundamentally realised the dilemma between trying to keep the big clubs happy and keeping their structures intact, and thereby had to strike a balance, setting a dynamic that would lead to the current situation - but keep tilting one way. In the autumn of 1991, at an extraordinary Uefa congress, the then 35 members voted in new proposals, this time primarily put drawn up by Mendoza and former Rangers secretary Campbell Ogilvie. The quarter-finals would be replaced by a group stage, and league systems would be part of the competition for the first time. Even more important than that structural change, though, Uefa contracted the marketing company TEAM to sell it. The competition would the next season become the Champions League - to create what Fynn describes one of international sport’s two “supreme branded events” along with the NFL, right down to the distinctive classical anthem - an exclusive ‘family’ of corporate sponsors were signed up, and TV packages would be sold to the highest bidder, based on market share. Big clubs from the leagues with the largest TV markets would earn more and more money, accumulating more and more political capital Crucially, Berlusconi’s broadcasting model had properly permeated club football for the first time. The European game’s governing body had adopted many of its principles, as would the Premier League and many of the continents major clubs, bringing huge finances into the game - but also greater disparities than ever before. Big clubs from the leagues with the largest TV markets would naturally earn more and more money, accumulating more and more political capital, to the point more and more changes to the Champions League were inevitable. Finally, with two of this week’s fixtures offering the clearest examples in Barca-PSG and Arsenal-Bayern, we have the regular “television spectaculars” Berlusconi so envisaged. He probably didn’t envisage them, however, without Milan. That team he created, however, might still be the most influential in history. Because, just as they were changing football on the pitch with Arrigo Sacchi’s tactical ideas, the club were also changing football off it through Berlusconi’s economic ideas. And, if it was fitting that the first leg of the Real-Napoli tie was so off-putting given the change that would follow, it was equally fitting the return would give a sign of what was to come; what was capable - both in terms of the event, and the takings. This truly was the “television spectacular” Berlusconi desired. In front of a raucous 82,231 crowd at Napoli’s San Paolo stadium, and with Brazilian star Careca back in the team after injury, the revenge-driven home side finally did what Maradona demanded and “battered” Real in the right way. If only for 44 enticingly intense minutes. That Real team never got beyond the semi-finals, and were the very next season hammered 5-0 by Milan in a historic landmark of a game Defender Giovanni Francini had set the occasion alight by making it 2-1 after just after the half-hour, and Napoli could have added many more before Careca - of all people - missed a fine chance on 40. Within four minutes, Emilio Butragueno had scored the decisive goal. Real were through. If history regularly repeats itself, it’s interesting how so many of the same debates do, too. In the aftermath of that game, Maradona’s European pedigree was questioned, while Butragueno’s clinical brilliance was widely praised. Neither would actually end up winning the European Cup, as that Real team never got beyond the semi-finals, and were the very next season hammered 5-0 by Milan in a historic landmark of a game. At the time, though, Real were convinced they were on the brink. They even celebrated that victory in an unusually ostentatious manner. Beenhakker was remarkably moved to declare a mere first-round win - for a club that had then won the competition six times - as “a result for history”. It was to prove exactly that, but not in the way he imagined. The future could already be imagined from Napoli’s earnings from the game. They received 10,000 million lira due to both ticket and television sales, estimated at that point to be a world record. The die had been cast - and is still rolling. The Champions League continues to gradually change according to the preferences of big clubs, if at a somewhat glacial pace. “The big clubs never have enough money,” Fynn says. “That’s why you can never satisfy them, whatever changes you make.” Right now, what generally happens is that we see a lot of the same clubs, and a lot of the same fixtures in the latter stages of the competition - to the point Real and Napoli is again a novelty. It is thereby a fixture that will forever remain unique. Read More Pep’s future and Premier League charges – Where next for Man City after treble? How Pep Guardiola can become the undisputed greatest manager Man City fans feel let down by Uefa’s ‘shambolic’ organisation of Istanbul final Football rumours: Wilfried Zaha eyes move to Paris St Germain The sporting weekend in pictures Pretty Woman makes Pep Guardiola’s day as Julia Roberts hails Man City champions

2023-06-12 18:49

Silvio Berlusconi obituary: Scandal-ridden Italian billionaire, media mogul and the king of comebacks

Silvio Berlusconi, the boastful billionaire media mogul who was Italy’s longest-serving premier, despite scandals over his sex-fueled parties and allegations of corruption, has died. A one-time cruise ship crooner, Berlusconi used his television networks and immense wealth to launch his long political career, inspiring both loyalty and loathing. To admirers, the multiple-time premier was a capable and charismatic statesman who sought to elevate Italy on the world stage. To critics, he was a populist who threatened to undermine democracy by wielding political power as a tool to enrich himself and his businesses. Born in 1936 in Milan to a bank clerk father and housewife mother, he attended a Catholic college, the start of a complicated relationship with the church, which supported him until the mounting allegations of sleaze “superceded the limits of decency”, in the view of at least one weekly Catholic newspaper. His capacity to entertain emerged early when he worked on cruise ships and played bass with a band, performing George Gershwin hits like “I Got Rhythm” in the dancehalls of Milan before being sacked for devoting more time to flirting with punters (“marketing and PR”, he called it) than playing music. After graduating in law, Berlusconi turned down a job as a cashier at the bank where his father had worked in order to strike out as a property developer. His ambition was notable. To pull off an early make-or-break deal, he persuaded a secretary to tell him when her pension fund director boss would be taking a seven-hour train journey so as to ensure he could secure the seat next to him. Later, when the flight path put off buyers over his Milano 2 residential development, he had alternative routes opened. A modest plan to make his homes more attractive by offering a local cable TV service, Telemilano, which showed light entertainment and reruns of American soap operas such as Dallas, grew into a network of local channels until, by the end of the 1980s, his trash TV empire of game shows and barely-clothed hostesses came to dominate Italian airwaves. As well as hauling in advertising revenue, Berlusconi’s channels allowed him to give favourable coverage towards friendly politicians who helped him protect his commercial interests, which now included publishing houses and the football team AC Milan. When he entered politics himself, these contacts would prove indispensable. The Clean Hands corruption probes that took out a generation of Italian politicians eventually provided the motivation for that move. Power, he reasoned, would not only protect himself from prosecutors but allow him to defend his businesses. Headline-grabbing proposals included a million new jobs and lower taxes. A political outsider positioned as an enemy of the establishment, Berlusconi was in many ways a prototype for Donald Trump. Running a successful Serie A side like the “rossoneri” was one of his main qualifications for high office, he felt. When challenged by an economist over his tax plans, he replied: “How many intercontinental [football cups] have you won?” In 1994, he took 21 per cent of the vote in the general election and found himself prime minister, beginning a two decade-long domination of Italian politics through which he shamelessly advanced his own interests. His personal lawyers, now on the state payroll as MPs, spent their time drawing up laws to get him out of trouble, including immunity from prosecution for the prime minister and a tax amnesty that saved his company 120m euros. His communication minister meanwhile amended competition rules allowing him to retain his media empire. His calling to international relations was evident when he made himself foreign minister as well as prime minister, wooing foreign leaders such as Tony Blair and Putin by inviting them to his James Bond-esque Sardinian villa, complete with fake volcano. Cherie Blair described her evening there as the best of her life. But gaffes such as calling America’s first black president Barack Obama “suntanned” and suggesting a German MEP should play a concentration camp guard made him an international laughing stock. His standing took a further hit in 2009 when his second wife, Veronica Lario, publicly accused him of “frequenting minors”. When a 17-year-old Moroccan nightclub dancer, known as Ruby-the-Heartstealer, who was arrested for a petty crime, told police she knew Berlusconi, the claim set in motion a chain of events that would bring about the mogul’s downfall. Ironically, if Berlusconi had not interceded claiming she was the niece of Hosni Mubarak, the Egyptian despot, the case might have ended there. Investigators, their hackles raised by Berlusconi’s meddling, discovered that a harem of showgirls and models regularly visited his villas for sex parties where they received lavish gifts and envelopes of cash. The drip-feed of salacious details appalled even Italy, where mistresses are less taboo for rich men. Thousands took to the streets in protests that expressed women’s frustration at their humiliating role in Berlusconi’s Italy. But, ultimately, it was not the “bunga bunga” parties that undid him, but his inability to cope as Italy’s debt reached unsustainable levels in 2011 and he was forced to resign in favour of technocrats. Out of office, he remained in the spotlight, thanks to his own media empire and as the defendant in dozens of trials, throughout which he claimed he was the victim of a plot by a left-wing judiciary. After years when, Teflon-like, he had wriggled out of every writ, his eventual conviction for tax fraud in 2014 and subsequent sentencing to community service in a home for Alzheimer’s sufferers represented rock bottom, but, as usual, Berlusconi proved irrepressible, entertaining residents with bingo games and singalongs - a revival of his old cruise ship act. His final years went some way towards rehabilitating his image. He became the oldest member of the European Parliament, his centrist pro-European politics far preferable, in the eyes of German chancelleor Angela Merkel, to the dangerous populist ideals that surged in Europe. When, in February 2021, his party joined a government led by that most establishment of figures, former European Central Bank chief Mario Draghi, his triumphant comeback was complete. His return to government represented an unlikely final twist in the story of a figure who had risen from selling electric hairbrushes to being the richest and most powerful man in Italy and the object of global fascination as (depending on your point of view): a media mogul, marketing genius, football club owner, political trailblazer, womaniser and showman. For every Italian that hated him for his monopolistic control of the media and abuse of power, there was another who admired his business acumen and was amused by his lowbrow larks. As the writer Curzio Malaparte wrote, Berlusconi’s qualities and defects “are the qualities and defects of all Italians”. Berlusconi is survived by 12 grandchildren and five children: Pier Silvio, Marina, Barbara, Eleonora and Pierluigi. Read More Perhaps the most surprising part of the Italian crisis is that Berlusconi has emerged as a selfless voice of reason Italy’s comeback kid: How Silvio Berlusconi has managed to re-enter politics, despite all the scandals Silvio Berlusconi tells female reporter her handshake is so strong 'no one will want to marry her' Silvio Berlusconi dead: Billionaire former Italian prime minister dies aged 86

2023-06-12 17:15