When Sergii Naumov took over as chief executive at one of Ukraine’s biggest state banks before Russia’s invasion, his job was to privatize it. Now he’s glad he didn’t get the chance.

The role of Ukraine’s banking system is one of the less told stories of the nation’s resilience. It survived the loss of assets to occupation, power outages and a 30% collapse in GDP without bank runs, service interruption or any significant closures. State-controlled lenders like Naumov’s Oschadbank JSC have played a part.

“Generally, when you have this state-owned economy it is not good, but during the war it helped,” says Naumov. “We know what our mission is.”

Before the war, the state-run lenders that control about half the system’s assets were seen as part of the country’s problem. They were notorious for poor governance and backroom deals with their government owners.

Now they’ve become an important source of funding for an economy under assault, pushing subsidized loans and helping to fund a cash-strapped state, even as private lenders pulled back to reduce their exposure to risk.

Whereas overall bank credit to households and private sector companies contracted last year, Oschadbank increased lending by 11%, and by 81% for small- and medium-sized companies. They’d loan more, as there is plenty of liquidity in the system, according to Naumov, but in a brutalized economy with high interest rates, demand for credit is low and all but non-existent for mortgages.

The financial sector as a whole has been profitable since the start of the war. And with dividend payouts banned for private lenders, those banks have added to their cash buffers. The weighted average of capital adequacy ratios across the sector is up 3 percentage points, to 14.3% — well above the 10% requirement stipulated by the Ukrainian central bank.

Some of that liquidity is also channeled to finance the state budget, supplementing the aid Ukraine receives from international donors.

Soldiers on the battlefield earn high salaries by Ukrainian standards and get paid via state lenders. Some people also consider state-owned banks safer than their commercial rivals during a war.

As a result of those factors, state banks find deposits rising, without having to offer high interest rates to attract them. That in turn creates a huge pool of cheap money the banks can lend back to their owner, the government, purchasing its bonds at a time when there’s no market demand for the paper.

All the same, at a time when that stability is partly enforced, the International Monetary Fund has warned of the risk of blow ups.

“Although the financial system remains stable and liquid thanks to extensive emergency measures, continued vigilance is warranted given the true health of the banking system remains opaque, and the risks of further shocks persist,” the Washington-based lender said in a June 29 report.

The central bank is conducting an asset quality review for the country’s 20 largest banks, accounting for 90% of the sector’s assets, with results to be published by March.

Despite the role that state lenders have provided in sustaining the wartime economy, both the IMF and Ukraine’s central bank want to privatize all state lenders other than Ukreximbank JSC, which finances trade, once the war ends.

They argue that such measures are necessary to avoid distorting competition and the central bank is already encouraging state lenders to clean house in preparation. Ukraine’s $15.6 billion IMF loan program calls for bank privatizations and they will be key to unlock $115 billion in further aid.

“I have not seen any good examples in general of how the state managed state-owned enterprises, including banks,” said Kateryna Rozhkova, first deputy governor of the National Bank of Ukraine, responsible for financial stability.

Before Russia’s invasion, Naumov agreed with them. But after his experience keeping funds flowing to a country under attack, he says that two banks should remain under state control.

“Russia will not disappear in the next years,” he says. “They will be with us all the time.”

In the short term, at least, the state’s share of the financial system is about to get even bigger. On July 20, the central bank started the process of nationalizing Sense Bank JSC, previously Alfa-Bank Ukraine. That institution was solvent but owned by sanctioned Russian businessmen including the billionaires Mikhail Fridman and Petr Aven.

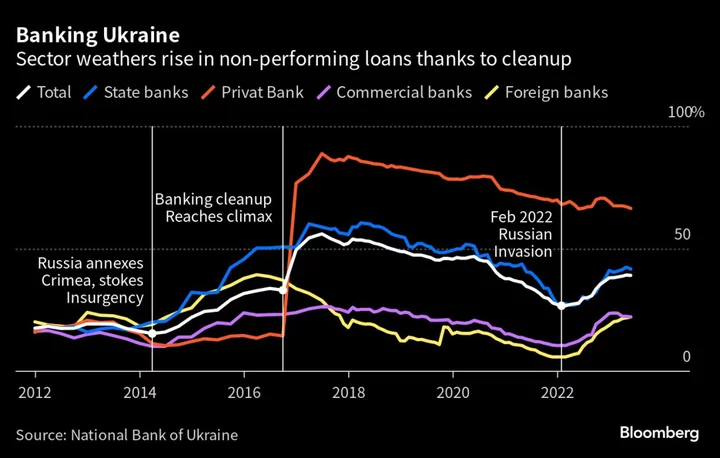

Rozhkova argues that the root cause of Ukraine’s financial resilience isn’t lending by state banks, but the clean up of a sector that until recent years had been riddled with related party lending and hidden losses. That process saw state-owned institutions handed funds by the state to recapitalize and saw the country’s largest lender, Privatbank, nationalized.

Speaking at her office in the central bank’s elegant 1905 headquarters — built when Kyiv was part of the Russian Empire — Rozhkova said that state control of banks invariably distorts both market competition and regulation. She did acknowledge that state banks have served a vital purpose during the war, providing finance at a time of need, if only because of their sheer size.

More than 80 banks were closed in the years that followed President Vladimir Putin’s 2014 incursions into eastern Ukraine. Others, including state banks, were forced to recapitalize and undergo regular stress tests.

Asked what would be happening now if that clean up had not taken place, Rozhkova paused.

“It would have been a very, very deep crisis,” she said. “The sector would not be able to support the government, the economy or the people.”

Companies like Citius-S and A.M.P. Hydro can testify to the importance of state lenders. At the start of the war, the two small manufacturing companies fled Melitopol, the southern city that now lies in the path of Ukraine’s counteroffensive.

Both had to leave their equipment behind and lost most of their staff. When they knocked on Oschadbank’s door for the capital needed to start over about 1,200 kilometers (750 miles) to the West, in Lviv province, they had no collateral or cash flow to offer.

“We even had to destroy our machinery, to make sure the Russians couldn’t use it,” says Alex Serov, the 60-year-old owner and director of Citius-S, which makes bullet-proof glass and armored security vans.

What they did have was good records and business plans.

With help from international organizations such as USAID, Serov and his daughter Anastasia sat down with Oschadbank to work out a 12 million hryvnya ($328,000) loan.

Now they’re back up to 50% of their pre-war output, pushing out about 15 vans per month. They’ve refurbished two abandoned warehouses and Serov has his eye on a third as he considers reviving another former business, making ambulances.

A.M.P. Hydro was an even less likely candidate for financing. Not only did it have no collateral, but the company had stopped payments on a 10 million hryvnya loan it took to buy equipment abandoned in Melitopol. It was now asking for a further 22 million hryvnya.

“First they thought it was funny,” says chairman Gennady Barabash, whose plant makes hydraulic cylinders.

But the company did have orders. So with 47 pages of conditions including resumption of payments on the bad loan, Oschadbank eventually relented.

Finding skilled staff is now a bigger problem than finance, Barabash says, as he tries to ramp production back up to pre-war levels.

More strains are likely to appear among Ukraine’s banks as the war continues and households and companies run through their savings. A staggering 49% of Oschadbank’s total loan portfolio is non-performing, although those are 100% provisioned, according to Naumov.

Those NPLs are a legacy issue, he says, driven by loans that already had been restructured before the war and then got into trouble when the economy cratered.

For loans made since the invasion, the non-performance ratio is just 0.4%, even if that figure flatters because most borrowers have had little time to get in trouble yet.

As he contemplates the prospect of operating under the threat of Russian aggression for years to come, Naumov argues that it’s critical for the Ukrainian state to retain the capacity to channel funding to companies like Citius-S and A.M.P. Hydro in extreme situations.

“War showed a lot of things,” he says.

(Corrects function of first deputy governor of Ukraine's central bank in paragraph 16 of story originally published July 30)

Author: Marc Champion , Olesia Safronova and Volodymyr Verbyany