When Olayemi Cardoso takes full control of Nigeria‘s central bank this week, his biggest challenges will be to restore its credibility after eight years of mismanagement, boost confidence in Africa’s worst-performing currency and slow an inflation rate that’s among the highest on the continent.

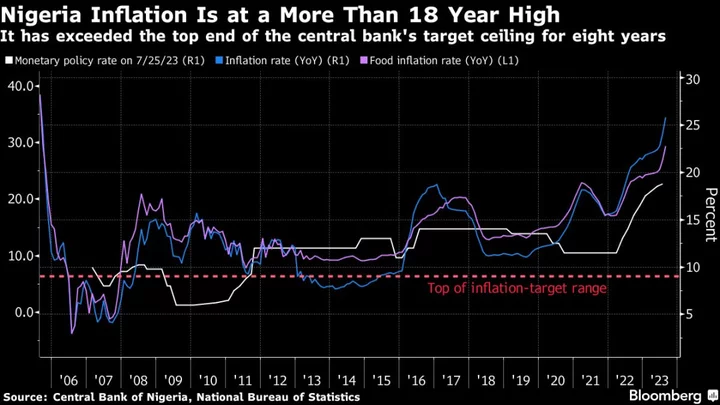

Since taking office in May, President Bola Tinubu has instituted a raft of new policies — scrapping a $10 billion annual fuel subsidy and liberalizing the foreign-exchange market. The reforms were much-needed, but crippled an economy long on its knees. The naira is in free-fall — hitting unprecedented lows — and gasoline prices have more than tripled, pushing the inflation rate to a more than 18-year high.

Through it all, the central bank has been leaderless — its last governor has been imprisoned since June, charged with fraud, which he denies.

“The economy is a few meters from going bust,” said Mosope Arubayi, an economist at IC Group in Lagos. The country risks defaulting on its debts, like its West African neighbor Ghana, if action isn’t taken soon, she said.

The nomination of Cardoso, former chairman of Citigroup Inc. in Nigeria, has offered a glimmer of hope to weary investors. A longtime adviser to Tinubu, Cardoso is widely expected to abandon the unorthodox policies of his predecessor, Godwin Emefiele, under whose nine-year tenure the central bank maintained multiple exchange rates and rationed dollars, repelling investment.

Read more: Nigeria Senators Back Ex-Citi Executive as New Central Bank Head

At his confirmation hearing on Tuesday, Cardoso, 66, ensured investors that the central bank would not be “hijacked by anybody,” and that a culture of compliance would be ingrained and its credibility restored.

“It’s a crusade,” said Cardoso, a longtime Tinubu adviser who served as the president’s economic commissioner during his 1999-2007 governship of Lagos state. “And we will be successful since the future of Nigeria rests on it.”

Bank in Turmoil

Cardoso takes over a central bank in turmoil — even its four deputy governors have been hauled in for questioning and forced to resign.

For eight years, Emefiele pursued a wildly unorthodox policy, marching in lockstep with then-President Muhammadu Buhari’s statist approach. He intervened in nearly every facet of the economy — banning imports of dozens of items including wheelbarrows and toothpicks, and doling out loans to everyone from rice farmers to Nollywood film producers and petty traders.

Cardoso will refocus the “CBN to its core mandate,” he said on Tuesday. “There is a need to pull the CBN back from direct development finance interventions into more limited advisory roles that support economic growth.”

Early on, Cardoso will need to focus on stabilizing the naira. There’s a $12 billion queue at the central bank for investors to repatriate profits, dividends and trade obligations as well as suppressed dollar demand, according to estimates by Goldman Sachs Group Inc.

“The immediate priority will be to be able to verify the authenticity and the extent of what is owed,” Cardoso said. “And then, of course, once we do that, we need to promptly find a way to take care of that.”

Wale Edun, Nigeria’s finance minister, said last week that $6.8 billion of overdue forward contracts owed by the central bank to domestic lenders is what is fueling volatility in the naira.

Dwindling Reserves

Cardoso will need to shore up the bank’s $33.3 billion of foreign-exchange reserves, about 90% of which have been used as collateral for dollar loans from foreign and domestic banks. He’ll also need to quickly raise rates, which will pit him against his old friend Tinubu, who called for lower borrowing costs in his inaugural speech.

The central bank will need to raise rates significantly and at the same time drain the market of naira liquidity, said Charlie Robertson, head of strategy at FIM Partners.

“Do both of those and show you are serious about stabilizing the currency,” Robertson said, adding “one-year yield of around 20% could make naira more interesting to hold.”

Higher rates would also add pressure to the government’s borrowing costs and worsen its fiscal position with debt service payments already consuming nearly all of its income. A rate hike would also hurt local businesses, put further pressure on inflation and send meager economic growth of 2.5% in the second quarter even lower.

“We will be going to evidence-based monetary policies,” Cardoso said. “We shall not the making decisions based on a whim.”

Tinubu has little room for fiscal maneuvering — debt service consumed 96% of revenue in 2022. Access to international debt markets is also limited, with the country’s credit rating six notches into junk territory and yields at double digits even after rallying on Tinubu’s initial reforms.

Strikes & Protests

The impact of Emefiele’s wayward central bank policy can be felt across Africa’s most-populous country.

The nation’s biggest labor unions have called for an indefinite strike from Oct. 3 over the sharp rise in the cost of living and are demanding a wage award to cushion the impact on workers. At least two Nigerian states have had to cut the number of working days to four from five to reduce the amount workers spend on transport.

Businesses have been hit by rising costs caused by the naira’s 40% devaluation in the wake of the currency reform. That’s pushed up interest expenses for those with dollar loans.

Faced with a backlash, Tinubu suspended further increases in gasoline prices. The central bank also reintroduced some of the controls around foreign exchange to stop the naira weakening further on the official market. That’s led to the reemergence of a nearly 30% gap between the official rate and the widely used unauthorized market rate.

Unlike Emefiele, a flamboyant character who held combative press conferences and tried to run for president while serving as governor, Cardoso is widely seen as a reserved institutionalist.

Nigerian tycoon Tony Elumelu said he was confident that the new central bank team is “very capable” and will be able to bring confidence and trust back into the economy. “We have confidence in the new central bank governor based on his credentials and his team and we believe that they will correct things,” he said in an interview with Bloomberg TV.

All investors want, he added, is an economy “where they can invest freely, as well as move their monies out, when it comes to remittance and repatriation of a dividend.”

(Updates with labor unions call for indefinite strike in second paragraph after Strikes & Protests subheadline)

Author: Anthony Osae-Brown, Emele Onu and Ruth Olurounbi