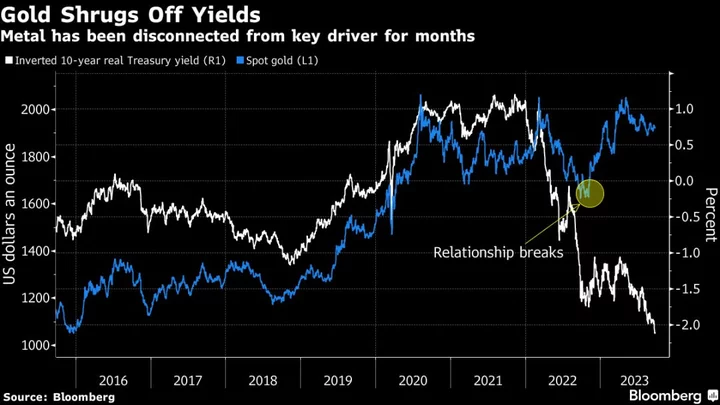

What determines the price of gold? For much of the past decade the answer was easy: the price of money. The lower rates fell, the higher gold climbed, and vice versa.

Gold is the quintessential “anti-dollar” — a place to turn for those who distrust fiat currency — so it seemed natural that prices would rise in a world of low real interest rates and cheap dollars. Or when rates went up, gold, which pays no yield, naturally became less attractive, sending prices tumbling.

Well, not anymore.

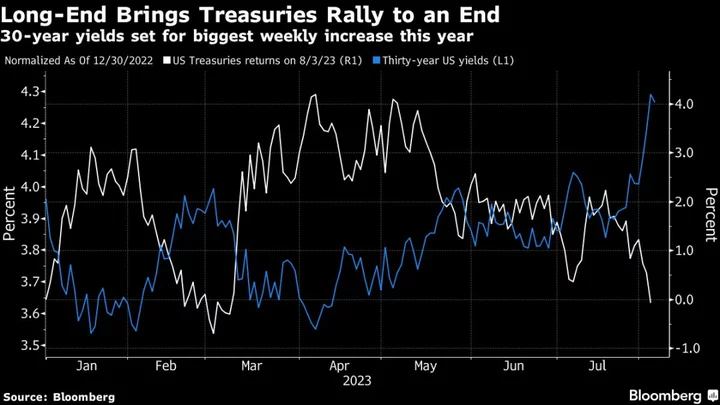

As inflation-adjusted rates soared this year to the highest since the financial crisis, bullion has barely blinked. Real yields — measured by the 10-year Treasury inflation-protected securities, or TIPS, — jumped again on Thursday to the highest since 2009, while spot gold nudged down a mere 0.5% the same day. The last time real rates were this high, gold was about half the price.

The unraveling of the relationship between gold and real interest rates could be a paradigm shift for the precious metal, leaving investors struggling to calculate its “fair value” in a world where the old equations don’t seem to apply. It’s also raising questions about if and when the old dynamic might reassert itself – or whether it already has, just from a new base.

So what’s holding prices up?

Analysts point to a combination of voracious central bank buying – led by China – and investors that are still betting a US economic slowdown will be good for gold, even when the regular playbook says it’s time to sell.

“Our models told us it’s $200 too expensive,” said Marco Hochst, a portfolio manager at Berenberg. Yet the firm’s 319 million euro ($340 million) multi asset balanced fund which he helps manage is still holding about 7% of its assets in gold. “In our view the future looks much more attractive for gold.”

There are various different models or calculations to assess the fair value of gold — many analysts create their own — but at their essence most reflect the basic principles of where bullion is trading compared with real US bond yields and the dollar. Normally money managers would sell the haven metal as the dollar strengthens and the interest paid by other safe assets like bonds and cash rises.

But they haven’t done so on the scale that would be expected, creating the large “premium” to where the models say it should be trading.

“I get no yield on gold, but I can get yield on cash. Where am I going to go?” said Anthony Saglimbene, chief market strategist at Ameriprise Financial Inc. “In that respect, I’m surprised at how resilient gold has been.”

The “premium” has endured for over a year, as a record gold-buying binge by central banks helped the metal withstand monetary policy tightening globally.

There are some initial signs that sovereign demand is starting to slow, making gold more vulnerable to downturns. Crucial to the outlook will be if institutional investors decide to sell up if prices test new lows.

However, some analysts argue that rather than breaking down entirely, gold’s relationship with its key drivers has simply been reset at a higher base.

That could allow it to set a record if yields or the dollar drop again, according to Macquarie’s Marcus Garvey, who sees prices rising to $2,100 an ounce next year as the US economy slows.

“There has been a level break higher in the nominal gold price,” Garvey said. “Once you get the financial flows as a tailwind, I think it makes a decent push higher.”

A litmus test may have been the turmoil that engulfed the US financial sector in March. Real yields and the dollar fell as Silicon Valley Bank teetered on the brink, triggering fresh inflows into gold-backed exchange traded funds.

Despite already trading at a lofty premium, the metal rallied to within touching distance of the record it set during the pandemic, but eventually slumped as the crisis eased and investors sold into the higher prices.

But others are more skeptical of a repeat, particularly with the threat of a banking crisis having retreated and bonds offering meaningful yields for the first time in years. With gold looking relatively expensive, it might struggle to attract meaningful flows even in a US slowdown.

“There are other assets such as long term bonds that can be used in the portfolio for the same purpose as gold, but come with carry,” said Marco Piersimoni, co-manager of the 6.2 billion-euro Pictet Multi Asset Global Opportunities fund, who has halved his allocation to the precious metal in the past 12 months. “In the current environment gold is not a very convincing diversification asset.”

--With assistance from Eddie van der Walt.