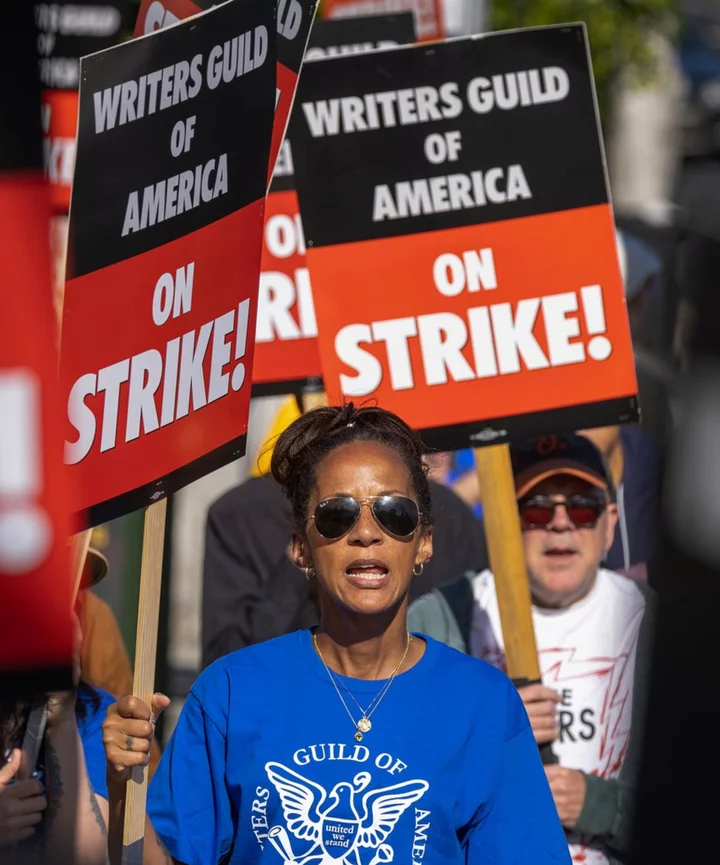

“Television is art,” screenwriter Sierra Teller Ornelas tells Refinery29 Somos. “It’s not meant to be made like a car.” If anyone knows the amount of creativity required for television writing, it’s her. She’s spent the last decade working on television shows like Brooklyn Nine-Nine and NBC’s Superstore, including leading her own production in Peacock’s much-loved but short-lived Rutherford Falls. She was recently developing a Latine sitcom for NBC called Amigos, but she’s not working now — she, along with thousands of others, is on strike with the Writers Guild of America (WGA). And this week, the group was recently joined by the 160,000-person-strong actor union, SAG-AFTRA.

Sierra’s car metaphor is particularly apt. Two hundred or so years ago, manual labor transformed thanks to industrialization. Now artificial intelligence (AI) is threatening to similarly impact the thinking class, which is why Dailyn Rodriguez — a WGA West Board member, TV writer, and showrunner for popular Latine-led titles like Queen of the South and The Lincoln Lawyer — says the contract negotiation is a “fight for the middle class.” It’s the first real labor battle about AI. As such, it can have broad, long-lasting effects on what work looks like, who still gets paid, and — in the case of TV and movies — what stories get told.

“It’s the first real labor battle about AI. As such, it can have broad, long-lasting effects on what work looks like, who still gets paid, and — in the case of TV and movies — what stories get told.”

Dailyn RodriguezIn an industry that has historically overlooked Latine creatives, Latina writers of varying experience and with different levels of involvement in the WGA agree that their battle is about two things: the economic struggle to keep their profession from becoming a gig and the existential threat of AI, including what it could mean for Latine representation in TV series and films.

In terms of pay, it does not look good for TV writers. Gladys Rodriguez, who’s worked on shows like Vida and Sons of Anarchy, shares, “I came into this industry in 2002. And [co-executive producers], which was what I am right now, they made so much money. It was an industry [where] you could buy houses, and you could buy multiple investment properties and be set. Now, people are struggling to even pay rent.”

It’s especially disappointing that the decrease in pay has occurred as the industry let in more women and people of color. Gladys continues, “It’s unfair. Peers that succeeded back then as Co-EPs mostly were white males. They’re doing the same work, same level as me, and making three times as much money.” For those newer to the business, it’s stagnant. “Most of the Latine writers that I know are probably operating two or three levels above their current level,” Sierra shares. “It’s very hard, for some reason, for people to give us the benefit of the doubt or take chances on us, which is galling because most of the Latine writers that I know have that work ethic — whether they are first-, second-, or third -generation — that their parents raised them with, of doing things better than everyone else and working twice as hard and really committing to the project. It’s so frustrating to see that just not translate in this industry.”

“We are the least paid, least represented demographic in this business. That’s not an opinion; that is a fact.”

Dani FernandezThere are many reasons TV scribes have seen their take-home salaries plummet, partly thanks to streamers like Netflix rewriting the rules. Where the old broadcast model made money for everyone — with storytellers gambling that theirs would be a successful show thereby setting them up to earn more with residuals — the current model doesn’t offer the same profit-sharing incentives. The new normal is visible in famous cases like the creator of Squid Game, Hwang Dong-hyuk, getting just enough money to “put food on the table” despite making Netflix $900 million, or The Bear writer Alex O’Keefe winning an award with a negative bank balance.

Shorter seasons with smaller writing teams have also contributed to the problem, resulting in less stability, less opportunity to learn on the job, and more time hustling to get that next role. That pattern means a notoriously competitive industry may now be boxing out people without familial wealth, which is concerning for Latine writers, a group that’s just starting to break into the business.

“We are the least paid, least represented demographic in this business. That’s not an opinion; that is a fact,” says Dani Fernandez, a writer, actor, and host who played herself in Disney’s Ralph Breaks the Internet. As such, she’s a member of both the WGA and SAG-AFTRA, the actor’s guild. They’ve been negotiating with the studios, too. And on Thursday, SAG-AFTRA walked out, too — a move Dani thinks will mean the strike will end faster. The writers have shut down a lot of filming, but some productions continued, just without script authors offering insight into their intentions or anyone re-writing pieces that don’t play well.

“We’re faring pretty poorly right now in terms of representation and our own ability to showcase our voices and our stories.”

Christina PiñaThe two groups certainly need each other. “Without writers, we wouldn’t have the words that we use as actors,” Dani says. “Without actors, then your stories [as writers] aren’t coming to life.” Both guilds worry AI will replace them, a trend they’re already starting to see and that may be damaging for the working people in the business, the ones who have made up the majority of casts and staff but never become household names like Shonda Rhimes or Ryan Murphy.

And that’s where most Latines in the industry fall. As a Latina showrunner, the top position a TV writer can achieve, Dailyn notes, “There’s only like a handful of us.” Latines are such a rare sighting in these roles that Sierra reports walking around on sets and being mistaken for a service worker (a job she’s done) rather than the boss. “We’re faring pretty poorly right now in terms of representation and our own ability to showcase our voices and our stories,” says Christina Piña, the chair of the WGA West Latinx Writers Committee and a strike captain who has written on network shows like the CW’s Charmed and Law and Order: Organized Crime.

And that scarcity of existing Latine content makes a future driven by AI all the worse for our community. “AI, as it’s been explained to me, is sort of this regurgitation, replication of previous data,” Sierra explains. “And if you look at the last 100 years of media and how Latinos and Latino people are depicted, it has not been great.” Dailyn is more direct, declaring, “It’s plagiarism.”

“If you look at past films, it’s really bad: the sidekick, the maid, the criminal, the end. So it scares me that you’re going to be working off a past history where we were historically not really included.”

Dailyn rodriguezWith so few Latine shows to draw from, an AI-led future is one where we’re stuck with the tired, limiting stereotypes. “That’s what terrifies me about using past data to greenlight projects. Because guess who wasn’t included in it? Us! We were not the leads,” Dani says. “If you look at past films, it’s really bad: the sidekick, the maid, the criminal, the end. So it scares me that you’re going to be working off a past history where we were historically not really included.”

And that’s something Christina agrees is troubling: “Certain Americans see us as second-class citizens, no matter how much money we make, no matter how we rise in society, no matter what college you went to. … If we don’t tell the stories that are as diverse as we all know ourselves to be as [Latine] people, then how do you expect traditional Americans to see us any differently? If they’re only seeing us one way, then we will always be one way.” She, like the other Latina writers Somos spoke with, sees her job as changing that narrative. Christina declares, “I just refuse to live in a country and to export media that puts us in a certain box and makes us seen as second-class citizens. That hurts my soul.”

The alternative — that future where more Latine people rise to the middle class and get the culture-making power that comes with it — might just hinge on the writers and actors who are striking today. “The writers are fighting for everyone,” says Dani because, as Dailyn put it, “everybody’s seeing the squeeze.”