Rising hopes of a soft landing for the US economy likely hinge on the Federal Reserve’s willingness to tolerate inflation markedly higher than it would prefer.

After taking a break from tightening credit last month, Fed Chairman Jerome Powell and his colleagues look locked in to raising interest rates by a quarter percentage point this week. The aim: To slow the economy enough to reduce inflation to its 2% target over time, without crashing the US into a recession — a proverbial soft landing.

The big question facing policymakers and financial markets is what comes next. Former Fed Chair Ben Bernanke said that this week’s rate increase may be the central bank’s last in a credit-tightening campaign that’s already seen rates rise by five percentage points.

But a lot will depend on how much inflation the Fed is willing to accept, and for how long.

In the absence of a recession, the jobs market looks set to remain tight, with demand for workers continuing to outstrip supply. That will keep wages elevated, pressuring companies to raise prices to cover their added labor costs.

“It’s going to be hard to get enough demand compression without a recession to get that price pressure out of the system,” said JPMorgan Chase & Co. chief economist Bruce Kasman. “I don’t think inflation is going to slide below 3% on a sustained basis” otherwise.

As a result, the risk is that the Fed will eventually have to raise rates further after this week’s increase, especially if the US doesn’t slip into recession later this year, Kasman said, though JPMorgan’s official call is that the July boost will be the central bank’s last.

“There’s really no evidence that the Fed has done to enough on stay on the sideline,” said Stifel Financial Corp. chief economist Lindsey Piegza, who sees the central bank eventually raising rates to 6%, from a range of 5% to 5.25% now.

Differing Paths

Prominent economists who were early in warning the Fed about inflation now differ over how it should proceed.

Allianz SE economic adviser Mohamed El-Erian argues that the US central bank should live with inflation around 3% and not put the economy through the wringer to get price rises down to its 2% target.

Former Treasury Secretary Lawrence Summers says that settling for a 3%-plus goal now is a bad idea and risks setting the stage for even-stronger price growth in the next economic cycle.

What Bloomberg Economics Says...

“There are several potential adverse supply shocks on the horizon that could reverse progress on inflation, ultimately prompting the Fed to resume hiking toward the end of 2024. ... For now, we’re characterizing the trajectory of rates as an ‘extended pause’ after July, with a non-trivial possibility that the Fed may resume hiking down the line.”

— Anna Wong and Stuart Paul, US economists

For full note, click here

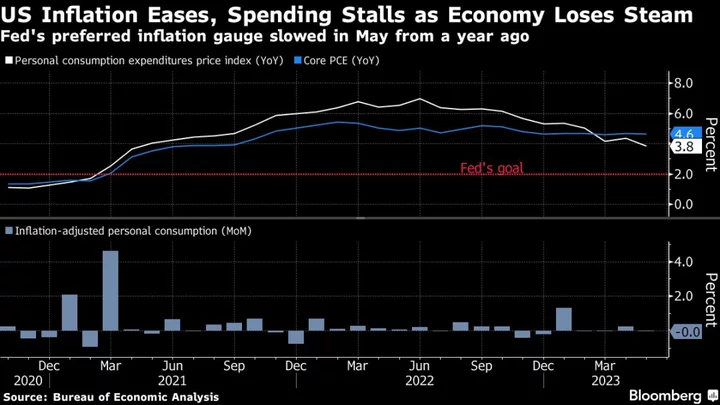

The inflation rate has come down significantly from its highs last year. To a large extent, that reflects an unwinding of price pressures arising out of the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, perhaps most prominently in the oil market.

Lowering inflation over the so-called last mile to an annual rate of 2% is likely to prove more difficult because it resides in the services sector, where prices tend to be stickier and where wages account for a bigger share of the costs of running a business.

The personal consumption expenditures price index, the Fed’s favorite inflation gauge, rose 3.8% in May from a year earlier. The core PCE price index – which excludes food and energy costs and which Fed officials judge is more representative of underlying trends – climbed 4.6%.

“Going down the last mile is hard,” said former Fed official Vincent Reinhart, now chief economist at Dreyfus and Mellon. “As recession becomes more likely, the Fed will give up its pursuit of price stability.”

Powell insists that the Fed is wedded to its 2% inflation target, though he’s conceded it could take some time to get there, perhaps not until 2025. He’s also acknowledged that a softer labor market probably will be needed to achieve that goal. But he’s betting that can be accomplished without a significant rise in unemployment and a recession.

Kasman said monthly inflation prints could remain soft over the next few months on the back of cheaper imports from China, an unclogging of global supply chains and a step-down in rent increases. But he argued that any relief is likely to be short-lived due to a continued tight labor market and companies’ increased willingness to raise prices.

El-Erian, who is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist, said the Fed is likely to face a choice in the fourth quarter: Press ahead with efforts to reduce inflation to target and risk breaking something in the financial markets or the economy, or recognize that getting to 2% won’t be easy and be prepared to revisit that goal down the road.

Consider 3%

He argues that a confluence of factors, including a reshuffling of global supply chains and the costs of transitioning to net zero greenhouse gas emissions, suggest the Fed should be shooting for 3% inflation, not 2%.

“If you’re bringing inflation from nine down to three, you probably aren’t going to lose credibility by saying we’ll stop at three instead of two,” said Peterson Institute for International Economics President Adam Posen, who’s also called for a higher target.

Summers, a paid Bloomberg Television contributor, though cautioned that settling for a higher inflation rate now could lead to trouble down the road as the economy’s underlying forces push prices upward.

“Whatever target they set is likely to be the low point for the cycle, not the average for the cycle,” he said. “The likelihood is that during a recovery inflation will increase.”

“The chances of a soft landing with inflation below 3% are larger than they were but still well short of 50%,” he added.