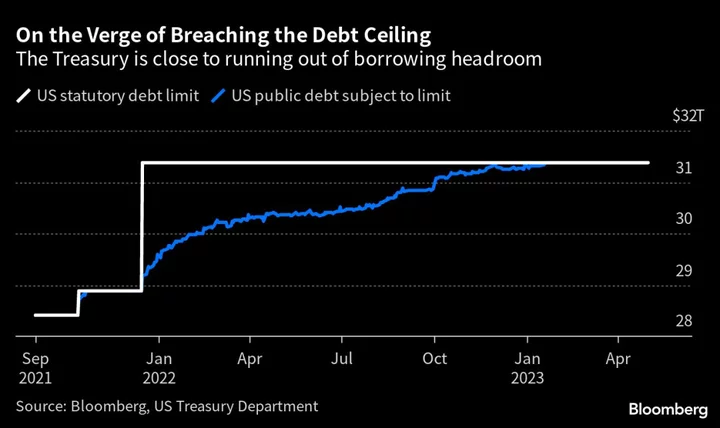

Investors have jacked up sharply the premium they demand to hold US paper that’s most at risk of default if Congress and the White House fail to strike a deal on the debt ceiling.

While broader financial markets remained relatively sanguine still about the prospect of a resolution eventually being found, the yields on securities maturing in early June have leaped once more. The rates on June 6 bills jumped more than 40 basis points on the day to around 5.84% and June 1 instruments were up over 30 basis points at 5.65%, showing that investors are shunning instruments that would be among the first to default if the administration were to exhaust its borrowing headroom early in the window that Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen has warned about.

The moves come as negotiations between the White House and Congressional leadership grind on, with President Joe Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy set to meet later on Monday. They also follow fresh warnings from Yellen, who said over the weekend that the odds of the US being able to pay all of its bills by June 15 are quite low in the absence of a debt-ceiling fix. The Treasury Secretary said in a new letter on Monday that it’s now “highly likely” that her department will run out of sufficient cash in early June, and repeated her warning that the moment could come as soon as June 1.

Meanwhile, time is running out. The Treasury’s combined fiscal resources — the cash balance and extraordinary measures used to remain below the $31.4 trillion ceiling — continue to dwindle and the window for Congress to get legislation through is narrowing. The amount of cash in the government checking account rebounded to around $61 billion as of Friday, providing a modicum of respite as it seeks to eke out funding until a solution can be found to the ongoing debt-limit impasse. It had just $92 billion of special accounting gimmicks up its sleeve at the end of last Wednesday.

If Monday’s Biden-McCarthy meeting “fails to produce a pathway to an agreement, market volatility could increase on fears that Washington might not reach a deal before the X-date,” Stifel strategist Brian Gardner wrote in a note to clients, using the term for the point at which the government says it can no longer be assured of fulfilling its obligations. “The chances of reaching a deal by the end of the week are uncertain, given the apparent lack of urgency among significant blocks of lawmakers on both sides of the aisle.”

Wrightson ICAP projects that the combination of the cash balance and the remaining extraordinary measures numbers will drop below $50 billion on June 1 and fall further to the $25 billion to $30 billion range on June 8 and 9. If that happens, the administration could potentially struggle to make it through to its next big expected infusion of tax receipts around June 15.

“The June 1 forecast is low enough to be concerning,’’ Wrightson ICAP economist Lou Crandall wrote in a note to clients. “The even lower estimates for the following week would probably force the Treasury to take preemptive steps to prepare for potential payment delays.’’

Day-to-day projections for Treasury cash and borrowing room for the first 10 days of June become “more important as we get closer to the danger zone,” he wrote.

Of course, T-bills maturing after the potential so-called X-date — when the Treasury runs out of room to maneuver — have been trading with a significant yield premium for some time because of concerns about a default. But that premium has grown and the most notable dislocations are for securities those due in June.

The cost of insuring US sovereign debt against default with derivatives has also risen, signaling heightened risk, and attention is also beginning to turn to the major credit-rating agencies to see how they might react if the standoff goes down to the wire. Back in 2011, Standard & Poor’s opted to strip the US of its AAA rating even as a last minute solution to that year’s ceiling crisis was found, although Moody’s Investors Service and Fitch Ratings maintained their top scores for the country. Moody’s said last Wednesday that it was hearing the “right things” out of Washington, but the negotiations in the national capital have, of course, ebbed and flowed since then.

From Washington to Wall Street, here’s what to watch to gauge how worried observers should be and when they should be concerned.

The Bills Curve

Investors have historically demanded higher yields on securities that are due to be repaid shortly after the US is seen as running out of borrowing capacity. That puts a lot of focus on the yield curve for bills — the shortest-dated Treasuries. Noticeable upward distortions in particular parts of the curve tend to suggest increased concern among investors that that’s the time the US might be at risk of default. Right now that’s most prominent around early June. Yields pared their advance on Thursday amid optimism about a deal, but that drop has since been reversed. It’s not just early June securities that investors are circumspect about. Even if the Treasury can make it past the early June danger zone, there are still risks of a default during the US summer if no legislative fix is found. As a result, sales of slightly longer-dated bills are also lackluster: Monday’s offering of three-month bills went off at its highest yield since early 2001.

Related Story: Yellen Doubts US Could Still Pay All of Its Bills by June 15

X-Date Predictions

Underpinning the various moves in debt markets are differing estimates about when the government might exhaust its options to fund itself — commonly referred to as the X-date. While the administration has provided guidance that it might fall short as soon as June, prognosticators across Wall Street have also been running the numbers based on government cash flows and expectations around taxes and spending. Most strategists have pulled forward their baseline estimates to align more with forecasts out of Washington, although some remain hopeful that the Treasury might be able to stretch its resources until late summer.

Related Story: Goldman Says Treasury Will Drop Under Its Cash Minimum June 8-9

The Cash Balance

The US government’s ability to pay its debts and meet its spending obligations ultimately comes down to whether it has enough cash. So the amount sitting in its checking account is crucial. That figure fluctuates daily depending on spending, tax receipts, debt repayments and the proceeds of new borrowing. If it gets too close to zero for the Treasury’s comfort that could be a problem. The amount of money the US government has to pay its bills rose modestly at the end of last week, providing a modicum of respite as it seeks to eke out funding until a solution can be found to the ongoing debt-limit impasse.

Related Story: Biden-McCarthy Meeting Tees Up Tense Week of Debt-Limit Talks

Insuring Against Default

Beyond T-bills, one other key area to watch for insight on debt-ceiling risks is what happens in credit-default swaps for the US government. Those instruments act as insurance for investors in cases of non-payment. The cost to insure US debt is now higher than the bonds of — among others — Greece, Mexico and Brazil, which have defaulted multiple times and have credit ratings many rungs below that of the US.

Related Story: US Default Insurance Cost Eclipses Brazil, Mexico as X-Day Nears

(Adds Yellen comments, latest Treasury cash balance.)