As a living legend and universally acclaimed innovator of animation, Hayao Miyazaki releasing a movie is righteous cause for celebration to all lovers of cinema. Films like Kiki's Delivery Service, Spirited Away, Howl's Moving Castle, Ponyo, and The Wind Rises have not only been praised by critics but have become beloved by audiences around the world, and inspired untold artists — including Guillermo Del Toro, who introduced the film at its International Premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival.

In Miyazaki's distinctive hand-drawn style, he meticulously blends the real and recognizable with the surreal and uncanny. Thereby, this sensational storyteller builds worlds that are grounded in the familiar — like the wild-limbed run of a small child — but where the sky is no limit, full of broom-riding witches, a pig piloting planes, a soaring Totoro, and a moody shapeshifter with great hair.

With his latest, The Boy and The Heron, Miyazaki once more collides the known and the impossible to spin a yarn of fantasy and tragedy that leaves audiences dropped-jawed in awe, a bit heartbroken, yet bolstered by beauty and radiant empathy.

SEE ALSO: 11 films you'll want to see out of TIFF 2023What's the buzz around The Boy and The Heron?

Credit: TIFFThe movie opened this summer in Japan with a daring marketing plan. No trailers nor stills were released by Studio Ghibli. And as the plotline was inspired by — not directly adapted from — a 1937 novel, audiences had very little idea what to expect. Far from the studio burying the film with a lack of promotion, a single poster was released, because Ghibli believed that Miyazaki's name was all the selling point they needed. Their faith paid off. The Boy and The Heron's opening weekend box office in Japan was the biggest the studio had ever seen, surpassing Howl Moving Castle's record.

Part of this may be pent-up excitement, as Miyazaki's last film (The Wind Rises) came out a decade ago, then was followed by his announced retirement. With The Boy and The Heron, the 82-year-old visionary offered a comeback many fans couldn't have predicted, and he's done it with reliable aplomb. (As I write this, the movie boasts the lauded 100% on Rotten Tomatoes — though as Vulture recently pointed out this can be a distorted measure of success.)

Regardless, don't call this his "last film."

Talking to CBC Radio (via Gizmodo), Studio Ghibli executive Junichi Nishioka said of Miyazaki, "He is currently working on ideas for a new film. He comes into his office every day and does that. This time, he’s not going to announce his retirement at all. He’s continuing working just as he has always done.”

Admittedly, it's tempting to paint a picture that The Boy and The Heron is Miyazaki's swansong — especially as its story involves themes of mortality, legacy, and getting lost in one's work (and, yes, birds). Yet, romanticizing the film's creation isn't essential to appreciating it or celebrating him.

SEE ALSO: All the best Studio Ghibli films you need to watch right nowWhat's The Boy and The Heron about?

Credit: TIFFInspired by Genzaburo Yoshino’s novel How Do You Live?, The Boy and The Heron centers on Mahito Maki (voiced by Soma Santoki), a child reeling from the loss of his mother to a fire in Tokyo during World War II. In an attempt to move on, his father (Takuya Kimura) moves them both to her hometown, where the boy is told his aunt (Yoshino Kimura) will be his "new mother." Reeling from all this loss and change, Mahito is drawn to a strange heron and a curious tower that is rumored to be cursed.

Turning the battle against grief into an external struggle, Miyazaki propels his young protagonist into a slippery world of fantasy and horror, in which Mahito is challenged to rescue his mother from her grim demise. It's a quest, then. And this boy is its noble knight, far more ready to throw his life on the line in the hope of fantasy than to confront the reality that awaits at home.

The Boy and The Heron is visually lush and haunting.

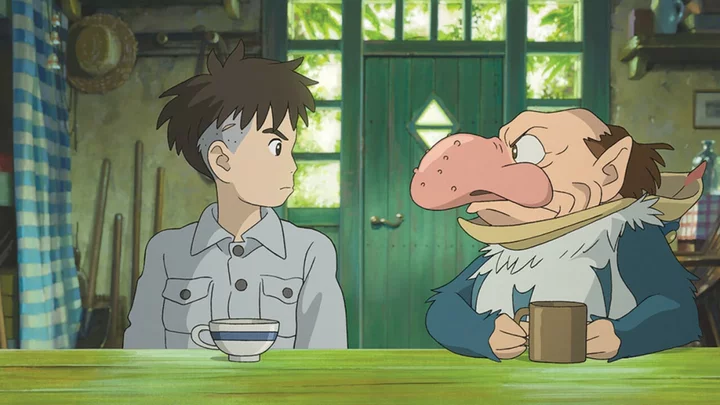

Credit: TIFFWhile promo reels for Studio Ghibli might play up the whimsy of his films, Miyazaki has long been drawn to tales of loss with children in danger at their center. Much like Spirited Away, The Boy and The Heron pitches its child hero — who can be cold or abrasive rather than an ever-plucky and precocious munchkin — into a world rife with creatures malignant and inexplicable. Here that journey begins with a heron, whose mouth cracks open to reveal bulging eyes and a long, bulbous nose, as if a snarling gnome hides in his gullet. From there, the imagery gets wilder, reveling in feathers and slippery forms, while treating time as a child's plaything.

There's a sea of compelling and mind-melting imagery within The Boy and the Heron. But I was most struck by how Miyazaki renders fire and water. In the film's first US trailer, you see a bit of both. Amid a field of muted grown-ups, fleet-footed Mahito races through fluttering streaks of orange, signifying disaster and flames. The hand-drawn lines of his face flicker in and of existence, suggesting the haze caused by the heat distorting the image. This animation doesn't just show you fire, it makes you feel that heat. While Mahito will not witness his mother's death, he will imagine it in a way terrible yet beautiful — not as if she burned, but as if she became the flames.

Later, in the tower, he is presented with a version of her, whole and resting. It's a fantastical twist on how a child might first confront death. At funeral viewings, the body is laid out in splendor, with make-up bringing a flush to greying cheeks, hair carefully laid, and clothes pressed and polished. They are there and not there, real and somehow not. When Mahito reaches out to touch his mother, she transforms slowly, elegantly, horrifyingly into water. It's this image I cannot shake, because this is how grief feels to me.

SEE ALSO: 'After Yang' review: Colin Farrell shines in soft sci-fi that hits hardIt's a slippery cruelty, where at times it can feel like the person gone is still here — as if they are just in the next room napping. But you can't turn to look for them, because then the absence becomes real. They slip away. To touch the dream makes it water, tears that can not be stopped from spilling.

Hayao Miyazaki relishes remembrance in The Boy and The Heron.

Credit: TIFFSuch strong imagery might knock the wind out of you, as it did me. But this movie is not an unrelenting barrage of mournful metaphors. In the tower, Mahito finds an unexpected way to connect to the mother he lost. In this, there is joy. Miyazaki contrasts this defiantly stoic little boy with a supporting cast of female characters who are bold, bouncy, snarling, silly, and above all else loving.

Perhaps the most splendid of these is a grumble of grannies, who swarm a curious package like jolly pigs on a trough. But a smirking swashbuckler (Ko Shibasaki) and a pint-sized adventurer (Aimyon) make for thrilling additions. They urge the hero to see his family not only for who they are now, but who they have been. In this way, he is given a view of life as a journey. At this moment, he might be stuck — emotionally or in a tower full of threat and wonder — but there is a path forward, you just have to find the door.

A heady exploration of grief and acceptance, The Boy and The Heron might catch off guard those fans who are hoping for a colorful romp with cuddly animal costars. (The animals here are colorful — but not so cuddly!) Despite its title pandering to such a concept — the Japanese release maintained the novel's name — this adaptation is about much more than a boy and a heron. But together, these two are an extraordinary launching point for a film that is lovingly layered, visually riveting, and ruthlessly sincere.

The Boy and the Heron was reviewed out its International Premiere at the Toronto International Film Festival. The movie will open in U.S. theaters Dec. 8.