The Bank of England’s newest rate setter Megan Greene said policy makers were right to raise interest rates in May and that they should “lean against” the risk of more persistent price pressures.

In testimony to Parliament, Greene said the BOE “needs to be concerned” about inflationary pressures and learn the lessons from the 1970s that those forces need to be reined in to prevent long-term damage to the economy. A “stop-start” approach to tightening risks a worse recession, she added.

The BOE “needs to proactively act to address inflation dynamics coming down the line instead of using its tools to react to inflation dynamics that already exist,” Greene wrote in written remarks released Tuesday as she appeared before the Treasury Committee.

The remarks suggest Greene may be more willing to back further rate rises when she joins the BOE’s nine-member Monetary Policy Committee than Silvana Tenreyro, who is departing after the June 22 meeting. Tenreyro is one of the most dovish members of the panel, voting for no change in rates.

Greene was careful not to discuss how she’ll vote on rates, saying she hasn’t seen the BOE’s forecasting models or how officials at the bank are using them.

An academic economist who has lectured at Brown University and the Harvard Kennedy School, Greene described herself as a “relentless extrovert” who will communicate the BOE’s view to a wide range of audiences. She has advised the San Francisco Federal Reserve, the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and the Kroll Institute in Washington.

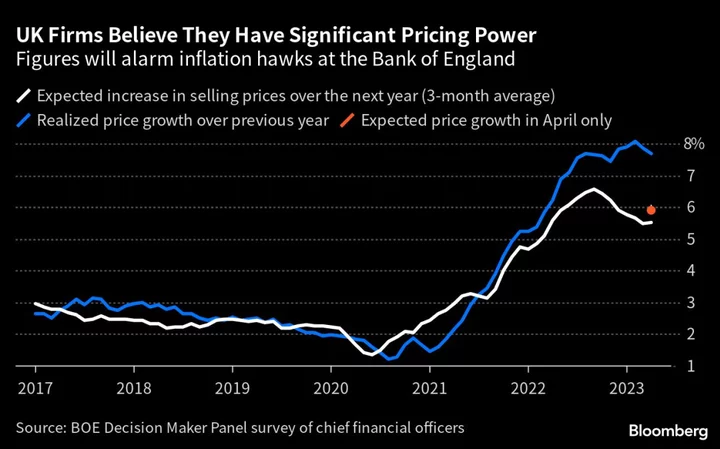

For now, Greene said inflation expectations in the UK are “pretty well anchored” but warned that policy makers need to ensure that they head off those pressures bedding down. She said there’s some evidence that companies have more pricing power.

Mapping out scenarios for the economy, she warned that inflation may prove persistent as corporates continue to rebuild margins and “this suggests consumer price inflation may remain sticky.”

Alternatively, if monetary policy is too aggressive, businesses could start laying off staff. “This would have significant implications for consumer confidence and for consumption and could prompt a recession,” Greene warned.

Britain’s growth potential has already “waned,” she added, and would continue to do so given the weak investment outlook.

“At the same time I see real output probably accelerating over the medium term forecast,” Greene said, explaining that this positive so-called output gap could build inflationary pressure. This was what the MPC “needs to look into.”

She explained Britain’s high inflation rate at 8.7% is above peer nations and was the result of high energy and food prices and the tight labor market. She did not link it to quantitative easing in the pandemic.

Inflation has fallen more slowly than elsewhere due to a lag caused in part by “the Ofgem price cap mechanism and in part because some firms are on fixed contracts that will not renew until later this year,” she added.

Her written remarks, drafted before a surprise jump in wages and drop in unemployment reported earlier Tuesday, suggested the labor market may be loosening, which “should take some upward pressure off of wage inflation, and therefore price inflation.”

Answering questions from lawmakers, she said: “The labor market is responding well to successive hikes.”

Pressed on whether the BOE is concerned about the cost-of-living crisis and the ability of consumers to pay for spiraling interest rates, she said, “in the environment we’re in, inflation hurts everyone. It hurts people on the lower end of the distribution most. The bank really needs to focus on getting inflation back to target.”

--With assistance from Elina Ganatra.

(Updates with comments from the testimony.)