A near-record number of long-term migrants came to the UK in the year ending June, laying bare the challenge for Prime Minister Rishi Sunak as he attempts to fulfill his vow of getting migration numbers down.

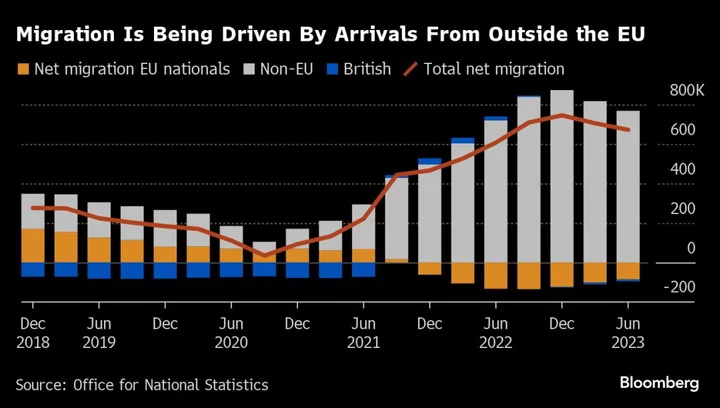

An estimated 672,000 more people moved to the UK than departed, according to the Office for National Statistics. Data for the year ending December 2022, which was already thought to see a record net number of migrants arrive, was revised up heavily to 745,000.

The numbers will be a tough read for Sunak ahead of a general election expected next year. His Conservative Party has promised to crack down on the number of overseas citizens coming to the UK after a desire to reduce migrant numbers fueled the Brexit vote.

But as Sunak faces the prospect of a stagnating economy with sticky inflation, driven in part by labor market shortages which have forced up wages, the need to recruit staff from abroad in areas where Britain doesn’t have enough home-grown skills has become increasingly clear.

Since the UK left the European Union, the Tory party can no longer attribute high migration numbers to free movement of people within the bloc. Instead, almost all migrants are now entering under government-sanctioned schemes, including humanitarian programs such as those available to Ukrainians and Afghans, work visas such as those issued to health and social care workers or others on the shortage occupations list, and as students.

Net migration to the UK in the year to June was entirely driven by non-EU nationals, with 768,000 more arriving than departing. That’s up from 179,000 just four years ago. By contrast, EU nationals continued to leave on balance, with net emigration of 86,000.

The ONS said it was too early to tell if the reduction from net migration in December was a consistent trend. But it added the estimates “indicate a slowing of immigration coupled with increasing emigration.”

Downward Trajectory

Madeleine Sumption, director of the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, said there was an “initial indication that net migration may have started a downward trajectory from the unusually high peak in 2022.”

“If past trends are any guide, net migration will continue to fall in coming years due mainly to more international students leaving,” she said.

There were also indications that Sunak was failing in his goal of driving down the number of people arriving through informal routes, such as on small boats across the English Channel.

In the year to June, 90,000 people immigrated for long-term asylum, up from 75,000 a year earlier. Of the 40,386 who arrived on “small boats,” 90% claimed asylum or were recorded as a dependent on an asylum application, the ONS estimated.

The figures will increase pressure on Sunak, who is facing discontent within the ranks of his own party for his failure to bring migration numbers down. A group of MPs who call themselves “The New Conservatives,” mainly holding seats in so-called red wall constituencies that traditionally voted Labour in the Midlands and the North, said that they were elected on a “solemn promise” to reduce migration.

“For the Treasury, there may be reasonable arguments for increasing immigration — because more people translates into more recorded economic activity — but the truth is the public won’t accept it,” the the group said in a statement Thursday. “Our voters can tell the difference between real economic growth that improves the standard of living for ordinary households, and the phantom ‘growth’ that importing ever-more people puts on a Treasury spreadsheet.”

Jonathan Gullis, Conservative MP for Stoke-on-Trent North and a member of the New Conservatives, told Times Radio that the prime minister and home secretary must take “drastic action now” to bring down migration.

‘Completely Unacceptable’

“I think it’s completely unacceptable and it will be unacceptable as well to the majority of the British people,” he said Thursday. “The last two years’ figures are truly shocking and appalling and the British public simply won’t stomach it.”

Jonathan Portes, professor of economics at King’s College London, pointed out that upward revisions to the Office for Budget Responsibility’s migration assumptions in recent years had added around 1.5% to forecasts for the size of the labor force, increased the size of the economy by around £40 billion ($50.2 billion) and nudged up tax revenues by £18 billion.

“In some respects this may be too pessimistic – recent migrants, especially from outside the EU, seem to have relatively high earnings,” he said on X, the site formerly known as Twitter. “Even more important (is that) high non-EU migration seems to be positively associated with productivity.”

While increased migration might also add to pressure on public spending, he said, “in a rational world, this is mostly good news for the UK.”

Of total immigration of 1.18 million people, over 80% of whom were not from the EU, the vast majority came for work, study and through humanitarian routes. The top five non-EU nationalities for immigration flows into the UK were Indian, Nigerian, Chinese, Pakistani and Ukrainian.

Of the non-EU migrants, 33% came through work-related visas — around half were main applicants and half were dependents. Those numbers were driven by migrants entering on Health and Care work visas, as staff shortages in the National Health Service have forced the UK to recruit from abroad.

Business Lobbying

Ahead of Wednesday’s Autumn Statement from Chancellor Jeremy Hunt, several business groups had been lobbying for more jobs to be added to the shortage occupations list. This dictates the people who can enter the country on worker visas, and several businesses are still finding it tough to recruit certain roles in the UK.

The government’s own Migration Advisory Committee had recommended adding pharmaceutical and laboratory technicians, building industry retrofitters to help meet net zero targets, and stablehands — but Hunt made no additions to the list.

Student-related visas accounted for 39% of non-EU immigration, with an increase over the year driven by a larger number of student dependents entering the UK. This may indicate a rush to bring families into the country ahead of a crackdown announced by Sunak earlier this year, which will ban masters and postgraduate students from doing so.

The ONS said analysis of recent student cohorts suggests more students are staying longer and transitioning onto work visas, a development that is potentially good for boosting the labor supply.

The number of people arriving to the UK under humanitarian routes, such as the Ukraine and Hong Kong visa schemes, fell to 83,000 from 157,000 the same time a year ago.

--With assistance from Eamon Akil Farhat.

(Adds more information from the report throughout)