Jimmy Hoffa, the legendary American union organiser, disappeared from a parking lot outside of the Machus Red Fox restaurant in Bloomfield Township, Detroit, 48 years ago on Saturday 30 July 1975. Presumed dead since the same date in 1982, his body has never been found, no one has ever been charged and the case remains unsolved.

Hoffa, 62, was last heard from at around 2.15pm that afternoon, calling his wife at their home in Lake Orion and a friend, Louis Linteau, at his office from a public payphone, griping that the two gentlemen he was supposed to be meeting for lunch had failed to show up.

He was subsequently spotted talking to several other men nearby before being driven away in a maroon car that one eyewitness, a truck driver, told investigators could have been a Lincoln or maybe a Mercury Marquis.

It might as well have been a hearse, for all the difference it made, for James Riddle Hoffa would never be seen again.

His own vehicle, a green Pontiac Grand Ville, stood abandoned at the scene, just where he had left it.

Long assumed to have been the victim of a mob hit, the visionary general president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters (IBT) – who dramatically expanded the union’s reach, influence and coffers between 1957 and 1971, before being brought down by scandal – certainly had more than his fair share of powerful enemies and shady associates.

Hoffa’s story – or, at least, versions of it – has frequently been told over the past half-century, often fictionalised through characters loosely based upon him in movies like Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America (1984) or more directly in Danny DeVito’s biopic Hoffa (1992) starring Jack Nicholson, James Ellroy’s Underworld USA novel sequence or Martin Scorcese’s recent The Irishman (2019) in which Al Pacino played the doomed labour leader.

But none of those projects have come close to cracking one of the most enduring true crime mysteries in the history of American public life.

What really happened to Jimmy Hoffa? Now that is a riddle.

Born on Valentine’s Day 1913 in Brazil, Indiana, Hoffa’s Pennsylvania Dutch father John was a coal miner who passed away from lung disease in 1920 when his son was just seven years old, prompting the family to relocate to Detroit, Michigan, soon to become the epicentre of the mighty American auto industry.

Realising he would need to grow up fast to support his mother, Hoffa left school at 14 to work as a stock boy for a grocery chain, where he soon took exception to the inadequate wages he received, the perilous terms of his employment and the inequality he saw all around him, which would only worsen in the aftermath of the Wall Street Crash of 1929 with the coming of the Great Depression.

Having learned to stand up for himself against workplace injustice, Hoffa quit in 1932 to work as a professional organiser with the Local 299 chapter of the Teamsters union, representing Detroit’s truck drivers and warehouse operatives.

As the organisation grew over the course of a combative decade, consolidating its power first locally, then regionally and finally nationally, Hoffa met the Polish girl who would become his wife, Josephine Poszywak, during a strike undertaken by non-unionised laundry workers in early 1937. They married that September.

Hoffa’s growing reputation and networking smarts saw him named chairman of the Central States Drivers Council in 1940, president of the Michigan Conference of Teamsters in 1942 and then president of Local 299 by 1946, all without moving so much as a single truck himself.

As a labour stalwart, Hoffa secured a draft deferment when the United States entered the Second World War by successfully arguing he would be of far greater service to his country organising industry at home than he might be deployed as a grunt abroad.

That also meant he was well positioned to reap the spoils of the American economic boom of the Truman years. By 1952, he was appointed international vice president of the IBT, serving as deputy to Dave Beck, who was himself succeeding Daniel Tobin, who had led the union since way back in 1907.

The IBT relocated its headquarters from Indianapolis to Washington, DC, three years later in order to be better placed to lobby Congress for its interests. It had never been more powerful.

Then, in 1957, Beck was indicted, convicted and jailed on fraud charges after being hauled before John McClellan’s Senate Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labour or Management Field. Hoffa was voted in as his successor as general president at the IBT’s convention in Miami Beach, Florida, that October.

However, Hoffa’s profile within the labour movement had inevitably increased his exposure to organised crime and he had been arrested earlier that year for allegedly attempting to bribe a McClellan Committee aide, prompting the AFL-CIO to expel the Teamsters from its ranks in passionate opposition to his appointment.

The air of notoriety surrounding Hoffa caught the attention of mob-busting US attorney general Robert F Kennedy during his brother’s presidency in the early 1960s and would see much of the organiser’s energies eaten up by legal scraps for much of that decade.

He was indicted for jury tampering in Tennessee in May 1963 after again being accused of attempted bribery and was convicted the following March, sentenced to eight years in prison and a $10,000 fine.

Four months later, while out on bail for the first offence, he was convicted at a second trial in Chicago, Illinois, on one count of conspiracy and three of mail and wire fraud for improper use of the Teamsters’ pension fund. This time he was sentenced to five years behind bars.

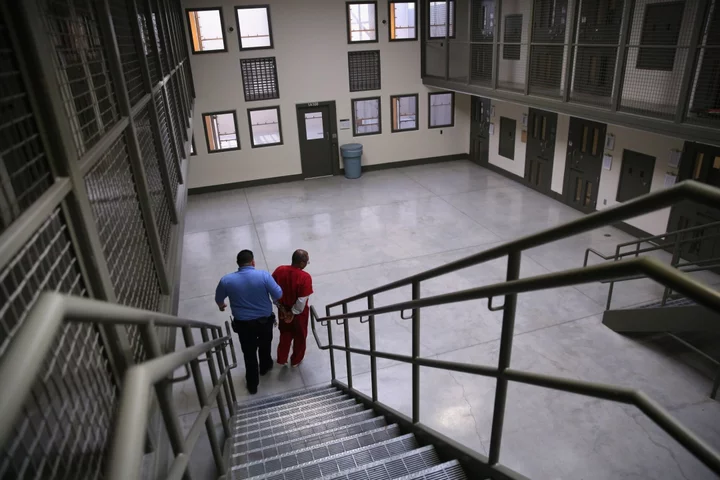

After spending three years unsuccessfully appealing those convictions – while simultaneously expanding the union and bringing almost all on-road North American truck drivers together under one National Master Freight Agreement – Hoffa was sent to Lewisburg Federal Penitentiary in Pennsylvania on 7 March 1967 to serve a 13-year aggregate sentence.

Despite the disgrace, he refused to resign and went on operating as IBT boss from Lewisburg, remaining in the role until 19 June 1971, when he was replaced by Frank Fitzsimmons, with whom he had a long association dating back to their Detroit days.

Hoffa was released from prison on 23 December that year, having served fewer than five of his 13 years after Richard Nixon commuted his sentence on the condition that he refrain from engaging in union activity until 6 March 1980, a stipulation he was bitterly opposed to and battled in court in the hope of being able to wrestle back the Teamster’s presidency, unmoved to consider retirement by the generous pension settlement the organisation had handed him.

The Mafia were among those opposed to his comeback ambitions, and one of their enforcers was Anthony “Tony Pro” Provenzano, a capo in New York City’s Genovese crime family with whom Hoffa had once been close but seemingly fallen out with while both men were incarcerated at Lewisburg.

Provenzano is one of the men Hoffa is supposed to have been dining with at the Machus Red Fox on the day he vanished. The other was Anthony “Tony Jack” Giacalone, a local heavy who may have been dispatched as a mediator to oversee Hoffa’s appeal for support to Provenzano. Neither would admit to having seen the labour veteran in Bloomfield Township that day and both seemingly had credible alibis.

What is known is that the car in which Hoffa is most likely to have been spirited away – a 1975 Mercury Marquis Brougham, after all – belonged to Giacalone’s son Joseph, who had lent it to one Charles “Chuckie” O’Brien, a Hoffa family friend. O’Brien may have been engaged to collect the old man in order to encourage a false sense of security.

His fingerprints would later be found on a 7-Up bottle in Hoffa’s Pontiac, although he continued to deny any involvement until his death in 2020.

When investigators examined the Mercury on 21 August, police dogs positively identified Hoffa’s scent in its upholstery, strongly suggesting he had ridden in it at least once. Later, in 2001, the advance of DNA technology enabled officers to locate a strand of his hair in the same car, although, again, that was not sufficient to trace it to a specific date.

After years of federal investigation had resulted in 16,000 pages of documents spread over 70 volumes but no outcome, leaving Hoffa’s wife Josephine to pass away in 1980 without answers, the FBI’s opinion on what had happened would be outlined by Arthur Sloane in his book Hoffa (1991).

In it, Sloane suggested the official verdict was that Northeastern Pennsylvania mob boss Russell Bufalino had ordered the hit and dispatched Thomas Andretta and the brothers Salvatore “Sally Bugs” and Gabriel Briguglio, alongside O’Brien, to carry it out.

The quartet then either killed Hoffa inside the vehicle or drove him on to an unspecified location and executed him there, perhaps cremating his body to prevent its rediscovery.

That broad outline was effectively confirmed on 16 June 2006 when The Detroit Free Press published the entire 56-page “Hoffex Memo”, an FBI dossier dating from January 1976 in which the bureau expressed its suspicions in writing, arguing the gangsters were concerned that a reinstated Hoffa might interfere with their control of the Teamster’s pension fund or even be persuaded to testify against them.

There are numerous quibbles with that theory, however. Experts often argue that Hoffa was too high-profile a target for the mob to assassinate in such a public manner and that his hopes of returning to the leadership of the union amounted to little more than a pipedream by 1975, his name too tarnished to represent a serious threat.

According to Sloane, former US prosecuting attorney Keith Corbett also believed that O’Brien was too unreliable to have played a part and that Vito “Billy” Giacalone, the younger brother of Tony Jack, was more likely to have been the fourth man.

A completely fresh theory appeared in 2004 with the publication of Charles Brandt’s book I Heard You Paint Houses, the basis for Scorsese’s The Irishman, in which the author argues that hitman Frank Sheeran did the deed in an empty house in Detroit after Hoffa had been delivered into his clutches, the subject having confessed as much in old age.

Bloodstains found on floorboards at the scene did not match Hoffa’s DNA, however, and it is often thought unlikely, as was the case with O’Brien, that an outsider might be trusted with such a delicate assignment by the notoriously tribal Italian-American syndicate.

Another infamous mob killer, Richard “The Iceman” Kuklinski, claimed in his own 2006 memoir that he was responsible, having been paid the princely sum of $40,000 to whack Hoffa.

Kuklinski claimed he drove the body to a New Jersey junkyard, sealed it inside a 50-gallon oil drum and set it on fire, later digging up the charred cadaver and placing it in the trunk of a car that was duly sold for scrap metal. That has likewise never been substantiated.

As to the final resting place of Hoffa’s remains, multiple sites have been inspected over the decades without yielding a result, from the now-demolished Giants Stadium in East Rutherford (a tip-off hitman Donald “Tony the Greek” Frankos offered in a 1989 Playboy interview) to a landfill beneath the Pulaski Skyway in Jersey City and even the Renaissance Building in downtown Detroit, now the 73-storey home of General Motors.

A farmer’s field, a swimming pool and a suburban driveway in Michigan have all been proposed and discarded while the wildest speculations imagine the missing man tossed from a plane by corrupt federal marshals into the Great Lakes (a theory courtesy of Hoffa bodyguard Joseph Franco, who had a book to sell) or ground up and disposed of in one of the quieter swamps of the Florida Everglades, an idea pitched to the Senate by self-described murderer Charles Allen in 1982.

Sadly, we may never know the truth about how Jimmy Hoffa, at one time one of the most famous faces in America, came to vanish into thin air, blown away on the breeze like an old parking ticket, never to be seen again.

Read MoreFBI say no sign of Jimmy Hoffa’s body under New Jersey bridge

Events in the disappearance of former Teamsters head Jimmy Hoffa

From serious to scurrilous, some of the many Jimmy Hoffa theories