He is the man who who has been leading opposition to Russia’s Presdent Vladimir Putin for a decade – organising mass protests and seeking to expose corruption by officials.

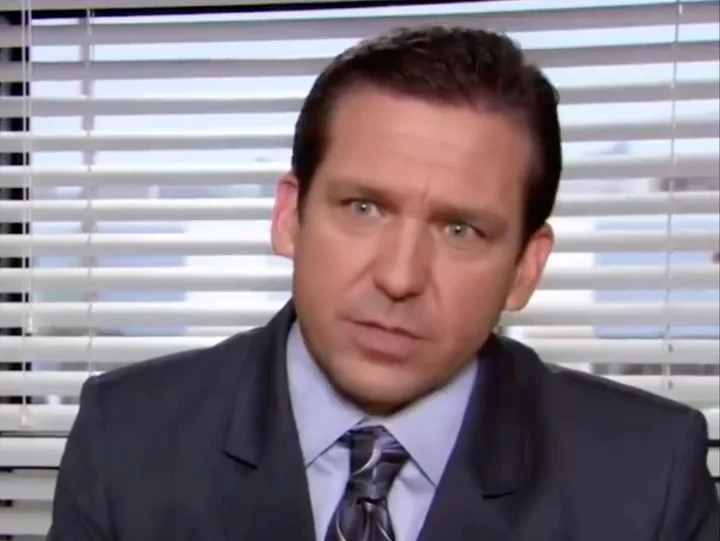

Alexei Navalny, 47, is now the country’s most prominent prisoner. He is currently serving sentences totalling more than nine years, having been arrested in January 2021 upon his return to Moscow after recuperating in Germany from nerve agent poisoning that he blamed on the Kremlin.

On Monday, he was in court facing the start of his latest trial on charges of extremism. Charges that could keep him behind bars for decades.

Mr Navalny, wearing his prison garb, looked gaunt at the session but spoke emphatically about the weakness of the state's case and gestured energetically. Mr Navalny has said the new extremism charges, which he rejected as "absurd," could keep him in prison for another 30 years. He said an investigator told him that he would also face a separate military trial on terrorism charges that could potentially carry a life sentence.

The trial came amid a sweeping Russian crackdown on dissent amid the fighting in Ukraine, which Mr Navalny has harshly criticised. Mr Nalvalny's supporters accuse Russian authorities of trying to break him in prison, to silence his criticism of President Putin, something the Kremlin denies. Much of the international community has hit out at Mr Navalny's imprisonment as politically motivated.

The Moscow City Court, which opened the hearing at high-security Penal Colony No. 6, didn't allow reporters in the courtroom and they watched the proceedings via video feed from a separate building. Mr Navalny's parents also were denied access to the court and followed the hearing remotely.

Mr Navalny and his lawyers urged the judge to hold an open trial, arguing that authorities are eager to suppress details of the proceedings to cover up the weakness of the case.

"The investigators, the prosecutors and the authorities in general don't want the public to know about the trial," Navalny said.

Prosecutor Nadezhda Tikhonova asked the judge to conduct the trial behind closed doors, citing security concerns. The feed from the session to media room was then cut, but it wasn't immediately clear if it was because the judge decided to close the trial or if it was for another reason.

The new charges relate to the activities of Mr Navalny's anti-corruption foundation and statements by his top associates. His allies said the charges retroactively criminalise all the activities of Mr Navalny's foundation since its creation in 2011.

One of Mr Navalny's associates, Daniel Kholodny, was relocated from a different prison to face trial alongside him.

Mr Navalny has spent months in a tiny one-person cell, also called a "punishment cell," for purported disciplinary violations such as an alleged failure to properly button his prison clothes, properly introduce himself to a guard or to wash his face at a specified time.

Mr Navalny's associates and supporters have accused prison authorities of failing to provide him with proper medical assistance and voiced concern about his health.

As Mr Navalny's trial opened, the Prosecutor General's office declared the Bulgaria-based Agora human rights group to be an "undesirable" organisation. It said the group poses a "threat to the constitutional order and national security" by alleging human rights violations and offering legal assistance to members of the opposition movement.

Russian authorities have banned dozens of domestic and foreign nongovernmental organizations on similar grounds.

In Berlin, the German government criticised the trial of Mr Navalny and reiterated its call for his immediate release.

"In case of of the opposition politician Alexei Navalny, the Russian authorities keep looking for new excuses to extend his imprisonment," government spokesman Wolfgang Buechner said at a briefing.

"The German government continues to demand of the Russian authorities that they release Navalny without delay," he added. "Navalny's imprisonment is based on a politically motivated verdict, as the European Court of Human Rights concluded back in 2017."

Asked whether Germany could provide any assistance to Navalny or observe the trial, Foreign Ministry spokesman Christian Wagner said German officials were doing what they could "on the few channels that we have," but acknowledged it was "very difficult at the moment" given the current state of relations with Russia.

It was not immediately clear which specific actions or incidents the new charges referred to.

One relates to "rehabilitation of Nazism" - a possible reference to Navalny's declarations of support for Ukraine, whose government Russia accuses of embodying Nazi ideology. A notion dismissed as ridiculous by Ukraine and its Western allies.

In April, Russian investigators formally linked Navalny supporters to the murder of Vladlen Tatarsky, a popular military blogger and supporter of Russia's military campaign in Ukraine who was killed by a bomb in St Petersburg.

Russia's National Anti-terrorism Committee (NAC) claimed Ukrainian intelligence had organised the bombing with help from Mr Navalny's supporters.

This appeared to be a reference to the fact that a suspect arrested over the killing once registered to take part in an anti-Kremlin voting scheme promoted by Mr Navalny's movement.

Mr Navalny allies denied any connection to the killing. Ukraine attributed it to "domestic terrorism".

Associated Press

Read MoreThe Body in the Woods | An Independent TV Original Documentary

The harrowing discovery at centre of The Independent’s new documentary

Russian court starts trial of opposition leader Navalny that could keep him locked up for decades

Navalny associate jailed by Russian court: ‘Another hostage in prison’

Russian court sends an associate of Kremlin foe Navalny to prison for 7 1/2 years