For the past two years, economists have been worrying about the risks of high inflation rates. But far less attention has been given to inflation's sibling: stagflation.

Stagflation is the combination of high inflation and a slowing economy.

Historically, low rates of unemployment compensate for some of the pain high levels of inflation bring. That's because businesses generally can only raise prices when people are earning enough to afford it. In contrast, when unemployment is high and people are cutting corners, businesses will have a tough time passing on higher prices to their customers, which keeps inflation low.

It's every central banker's worst nightmare when high inflation isn't accompanied by economic growth because there's very little they can do to improve the situation. Hiking interest rates to get inflation under control when unemployment is rising could push unemployment even higher. Cutting interest rates to stimulate the economy could produce more inflation.

The 1970s and 1980s saw prolonged bouts of stagflation. Now it's raising its ugly head again in several economies.

A look back in history: A spike in oil prices from the Arab oil embargo on the US and other countries that supported Israel in the 1973 Yom Kippur War raised the cost of living dramatically. But when the Federal Reserve tried to ease inflation by raising interest rates, the economy fell into a recession.

With the exception of a few months, the unemployment rate in the US stayed above 6% from 1974 to 1987, peaking at 14.5% in April 1980. Over the same time frame, inflation stayed above 5% and peaked in 1980 at 14.6%.

The current state of stagflation: Last year, then-World Bank President David Malpass warned that stagflation risks were high because of supply chain disruptions stemming from lockdowns in China and bans on Russian oil.

Malpass wasn't the only one sounding the alarm. "Higher food and energy prices are having stagflationary effects, namely depressing output and spending and raising inflation all around the world," Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said last May.

Their warnings were "valid during that period of time," said Lan Ha, head of economic research at Euromonitor International. However, the risks of stagflation ended up being much lower in part because last winter was relatively mild and China reopened in late 2022, she said.

What's happening now: The risk of stagflation varies significantly across different regions of the globe.

For China, stagflation is an afterthought. The country's Wednesday CPI report showed the Chinese economy slipped into deflation, with consumer prices falling for the first time in more than two years.

In contrast, Latin American countries haven't experienced stagflation "because central banks there were quick to hike rates to double-digit levels and have been successful in bringing inflation under control," said Andrew Kenningham, chief Europe economist at Capital Economics.

"I think most people would agree that it is already a reality in Europe," he said, adding that two prime examples are the UK and Germany.

In the UK, consumer price increases are cooling but remain elevated at 7.9%, according to the UK's June CPI report. That's almost four times the Bank of England's 2% inflation target level of inflation. The National Institute of Economic and Social Research said in its quarterly outlook report published Wednesday that it expects inflation to stay above the target through 2025.

And on GDP, the authors of the report are penciling in dismal growth. "Despite continuing to expect the UK to steer clear of a recession in 2023, GDP is projected to grow barely by 0.4% this year and by 0.3% in 2024, with the outlook remaining highly uncertain," they wrote. Taken together, NIESR economists are forecasting five years of lost economic growth, or prolonged sluggish GDP expansion, in the UK, which would be the longest period of lost growth since the Great Recession.

Germany, meanwhile, just came out of a brief recession and could soon enter another one given June's sharp decline in industrial production, a crucial part of the German economy.

What it means for the US: "The situation in Europe and the US is quite similar except that inflation in the US has been falling for longer and core inflation has come down further, so the stagflation [risk] there is easing," Kenningham said. Core inflation is a stripped-down measure of inflation that excludes volatile food and energy prices.

Also, the eurozone economy is more vulnerable to the ongoing war in Ukraine "given its proximity, both in terms of additional inflationary commodity shocks and wider instability in the region," Ha said.

Ha said she's monitoring how Russia's decision to withdraw from the Black Sea grain deal and extreme weather could push inflation higher and amplify the risks of stagflation across the globe.

How we're buying perfume could signal how we're feeling about the economy

If you're coming across more mini rollerball perfume you may unknowingly be getting a portal into the economic outlook.

Demand for more budget-friendly roll-on perfumes is up 207% so far this year over last year, followed by a 183% jump in cheaper perfume samplers and a 30% increase in body mists, according to Pattern, an ecommerce platform that analyzes online product search data across multiple product categories on Amazon and elsewhere, reports my colleague Parija Kavilanz.

Taken together this indicates consumers are pulling back on spending, despite more traditional economic indicators telling a much rosier story.

Even during economic downturns, price-conscious shoppers don't completely abandon purchases of pick-me-ups — high-end chocolate, perfume, expensive makeup — that make them feel better.

This is called the lipstick effect, when consumers spend on small luxuries even in a downturn.

"When you look at the economy, consumer confidence is a little shaken right now and consumers are tightening their purse strings," said Dallin Hatch, a data analyst with Pattern. But similar to the "lipstick effect," he said perfume now seems to be emerging as the luxury item of choice for shoppers during a period of financial uncertainty.

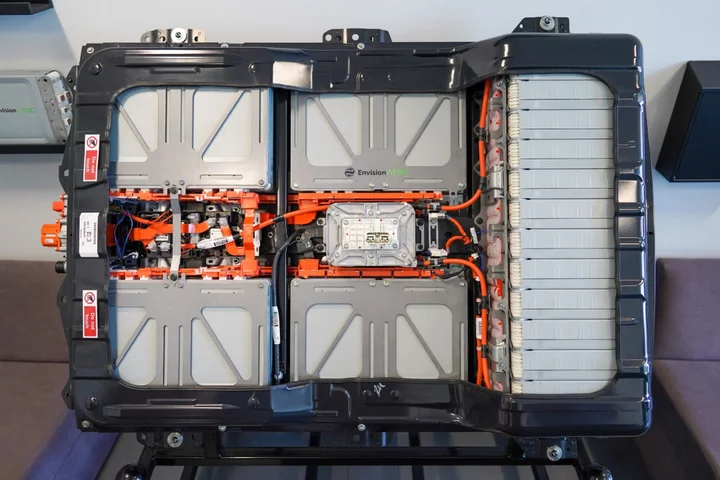

Under Biden, US oil production is poised to break Trump-era records

Critics accuse President Joe Biden of waging a war on the oil industry that is hurting consumers at the gas pump. And yet, on his watch, US oil production is poised to shatter all-time records set during the Trump administration, reports my colleague Matt Egan.

US oil output is now projected to rise to an average of 12.8 million barrels per day this year for the first time ever, according to federal estimates released Tuesday.

For context, that's about half a million barrels per day more than the prior annual record set in 2019. It's also more oil than any other country on the planet produces — the next-closest nation, Saudi Arabia, produces about 10 million barrels per day, according to OPEC, although voluntary output cuts have reduced that recently to 9 million.