When the commuter town of Monterosi, near Rome, applied for European Union money to build a preschool, a saga of frustration ensued that says a lot about Italy’s current problems.

Mayor Sandro Giglietti wanted to tap some of the €192 billion ($216 billion) in Recovery Fund cash earmarked for the country to bankroll an initiative aiming to attract families — a policy essential to boost population growth and female employment.

What should have been a simple task for a small building project took local officials 18 months to navigate as they encountered multiple layers of bureaucracy, fielding paperwork requests from both national ministries and the EU. Worsening it all was an inflation spiral that made costs hard to gauge and contractors cagey.

The cautionary tale shows the challenge faced by Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni as she tries to funnel the biggest aid program since Italy’s post-World War II reconstruction across the euro zone’s third-biggest economy.

That a local proposal so straightforward, and so fundamental to the country’s growth potential — encouraging parenthood and redressing low female workforce participation — almost didn’t happen, points to the risk that many other projects ranging from digital transition to hospitals to green energy will fail to get off the ground.

That’s a problem for Meloni’s right-wing government whose economic expansion plans are based on the full use of EU funds. In the case of the preschools, it also breaks her promise to voters that she would help Italians have more children and provide free childcare across the peninsula.

EU affairs minister Raffaele Fitto has said that Italy won’t be able to complete some of the projects needed to unlock EU funds by the 2026 deadline. The country is currently trying to renegotiate the terms of the EU Recovery Fund, with Brussels responding that it will allow some leeway but on a case-by-case basis.

“Financing will increasingly be delayed and withheld by the EU as Italy fails to meet agreed program targets owing mainly to administrative shortfalls and bottlenecks,” Eurasia Group senior analyst Federico Santi said in an interview. “This poses very serious risks to the economic growth outlook in the medium term.”

The government has estimated that the Recovery Fund will give a 3.4% boost to economic output by 2026. Santi says that with about one fourth of Recovery Fund projects facing issues “there are plenty of reasons to be worried.”

Monterosi’s problem building a preschool is particularly poignant in a country with low fertility rates and a shrinking population. That’s why about €4.6 billion in EU cash were made available to local communities to help with childcare.

“You need women to work for economic growth and you need more population for economic growth,” said Azzurra Rinaldi, head of the school of gender economics at Rome’s Sapienza University, and mother of three, who started a petition asking for more public preschools.

“The way to get both, is public childcare so mothers can earn more and have enough money to have more children, which is what the government says it wants,” she said.

In Monterosi, the biggest problem was dealing with an application process that was unfamiliar and complex, featuring differing requests from the various levels of government.

“I’d advise anyone else who’d like to try this to arm themselves with lots and lots of patience,” said Giulia Martoni, an architect advising mayor Giglietti on the project.

Additionally, changes in how much money would be allocated and increases in costs for things like building materials, meant scrambling for extra resources and renegotiating with the companies involved, according to Martoni.

But poorer towns didn’t even get that far, due to lack of expertise in dealing with the application process, something the state is now trying to address with advisers and courses.

“The government could do more to help,” said Gianpaolo Nardi, mayor of Castel San Pietro Romano, a small village east of Italy’s capital. “It would have been useful to actually train the people in local administration,” he said, recounting his own difficulties in accessing funds for re-qualification projects in his area.

The first tender for preschools at the end of 2021 only managed to assign €1.2 billion for lack of applicants. After Rome sent letters to municipalities encouraging submissions, further funds were assigned, but two more attempts were needed to get the full amount spoken for.

That process revealed other problems too: towns and villages need to be able to pay for staff to work in the new schools, and smaller municipalities, particularly those that need the most help in the south, often don’t have extra cash lying around, discouraging them from applying.

About 1,800 works on schools are planned across the country with completion scheduled at the end of 2025, according to the government’s website.

The preschool initiative saga is particularly relevant because of Meloni’s campaign promises and Italy’s demographic and economic challenges.

The country’s fertility rate of 1.25 children per woman is one of the lowest anywhere and the national statistics institute sees the population of 59 million dropping by 20% by 2070, or 12 million fewer people.

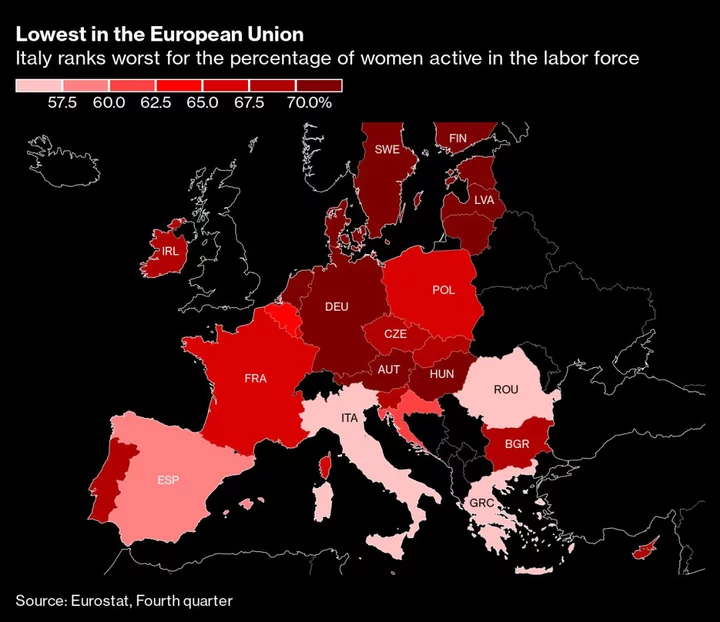

A dire record of productivity and growth could be drastically altered with childcare provisions that help women join the jobs market. According to a Bank of Italy study, if the country had the same female participation rate as the EU average, its workforce would increase by 10%, with similar effects on gross domestic product.

Italy has long struggled to disburse EU cash, and this time was meant to be different. In some places that may yet turn out to be the case, but it’ll require perseverance and energy from communities that have long learned to live with a rusted machine of state.

In Monterosi, which once witnessed a bloody Napoleonic victory against Neapolitan troops, the mayor is reflective as he looks back on his own battle against Italy’s bureaucracy.

“We got the money in the end, so it’s feasible,” Giglietti said. “But it was a tough fight — and a close call.”

--With assistance from Caroline Alexander and John Follain.