China is falling into a “balance-sheet recession” and needs to ramp up fiscal stimulus quickly to address the challenge, according to the economist who coined the phrase to explain Japan’s descent into stagnation in the 1990s.

“China is entering balance-sheet recession,” said Richard Koo, chief economist at the Nomura Research Institute, the research arm of Japan’s biggest brokerage. “People are no longer borrowing money,” due to concern about asset prices and the outlook for economic growth, and are instead “trying to reduce their debt” — a key element of the condition Koo defined decades ago.

Because of diminished appetite in the private sector to borrow and spend, the government needs to step in, he said. “The government should not waste time on monetary easing, or structural reform policies that economists love to talk about,” he said.

Koo’s concept has been widely discussed in Chinese economic and financial circles in the last year. He defines a balance-sheet recession as a situation in which households and businesses divert more of their income toward paying down debt, rather than consuming or investing. Koo argues that was a key reason for Japan’s descent into deflation, and for the slow US and European recoveries from the 2008 financial crisis.

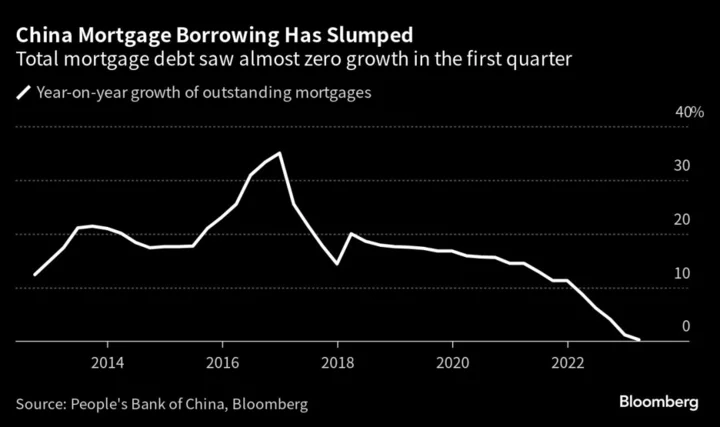

In China, evidence is seen in a slump in mortgage borrowing, decline in house prices and reluctance among private sector companies to borrow and invest. Inflation has fallen close to zero this year — another sign of weak demand in the economy.

But China’s awareness of the phenomenon should be an advantage, Koo said.

“There are already people talking about a balance-sheet recession in China — that was not the case in the US in 2008 or Japan in 1990,” he said. “The key difference is now the doctor knows what the disease is.”

The government needs to step in as a borrower-of-last resort to maintain spending that then provides households and business with income they can use to repair their balance sheets, until they are confident enough to resume borrowing.

“If the government puts in speedy, sufficient and sustained fiscal stimulus, then there’s no reason for Chinese GDP to collapse,” he said. The top priority is to ensure that builders complete unfinished projects, he added.

Japan Differences

While China’s property slump offers a parallel to Japan’s case in the 1990s, the Japanese property-price decline was much more extreme, Koo highlighted. “I don’t think China will allow that kind of thing to happen.”

Former IMF chief economist Raghuram Rajan pointed out another difference with Japan, which went through a “full-fledged banking crisis” decades ago. Rajan, who has also served as India’s central bank governor, said on Bloomberg Television Wednesday that China has “a fairly strong administrative system which can put losses where they should be — where they can be easily absorbed.”

Still, moves by China’s corporate sector to begin reducing leverage from around 2016 are a particular concern, Koo said, given how Chinese industries remain “massively competitive.”

“The fact that companies — which should be borrowing and expanding — are not doing so suggests that entrepreneurs are worried,” he said. Uncertainty about government regulation and the legacy impact of panemic lockdowns on corporate balance sheets could explain that, according to Koo.

One of China’s top economic think tanks, the China Finance 40 Forum, looked at Koo’s concept in a report on “damaged balance sheets,” released Thursday. While stopping short of saying China faced such a recession, it did call for stronger fiscal policy and for the government and central bank to directly inject capital into the private sector, or purchase private-sector assets.

“China needs to carry out strong counter-cyclical adjustment, but also needs the imagination and creativity to adopt targeted policies in response to damaged balance sheets,” the report said.

Another vulnerability for China is that globalization is more established now than it was when Japan’s economy was at a similar stage — meaning Chinese entrepreneurs can more easily move their operations abroad.

In addition, China’s population has peaked earlier in the development stage than Japan’s did. Along with a relatively greater dependence on construction, this indicates “the challenge China faces is probably much larger than Japan’s were,” Koo said.

China has space to expand government borrowing so long as private-sector savings remain high, he argued. However, “debt is already large, and you have to expand it to offset all the deleveraging that is going to take place — that could put some pressure on the Chinese financial market.”

(Updates with other perspectives, starting in second paragraph after ‘Japan Differences’ subheadline.)