To reach Ukrainian soil from Russia, teacher Olena Yevdokiyenko had to lug suitcases and push her mother's wheelchair for two kilometres in the dark.

Her family used a humanitarian corridor that is now the only entry point for Ukrainian citizens arriving from occupied territories via Russia's Belgorod region.

Although it works one-way only, the unpaved track through no-man's-land is still busy, more than a year and a half into the war.

"Those two kilometres seemed like 20," (12 miles) said Yevdokiyenko, resting with her teenage daughter and mother after crossing into Ukraine's Sumy region.

"We did it in stages -- walking a little bit with the bags, then we went back for granny, pushed her and then went back for the bags -- but it was very hard."

After vetting by Ukrainian officials in the border village of Krasnopillia, they stayed overnight at a centre in the regional capital, Sumy, run by local NGO Pluriton.

Resting under a fluffy cream-coloured blanket, Yevdokiyenko, 48, says she decided to leave the Russian-controlled Lugansk region after neighbours started calling her a "Nazi" and a "Ukrainian bitch".

The primary school teacher refused to get a Russian passport or use Russian workbooks.

"I became an outcast," said the cheery-looking woman surrounded by suitcases and bags of her mother's medicines.

"They started calling me names, making threats, there was a lot of pressure."

- 'Plot to blow us up' -

"I was (later) told there were also two attempts to blow us up with a hand grenade, so there would be no trace left of us."

Her family's house in a front-line village has been destroyed by shelling.

Her mother, Raisa Dеmyanenko, a 69-year-old retired teacher, was tearful, saying she was only now realising the family "had lived through horrors".

The family were getting free transport and basic accommodation in Kyiv, where Yevdokiyenko hopes to find work.

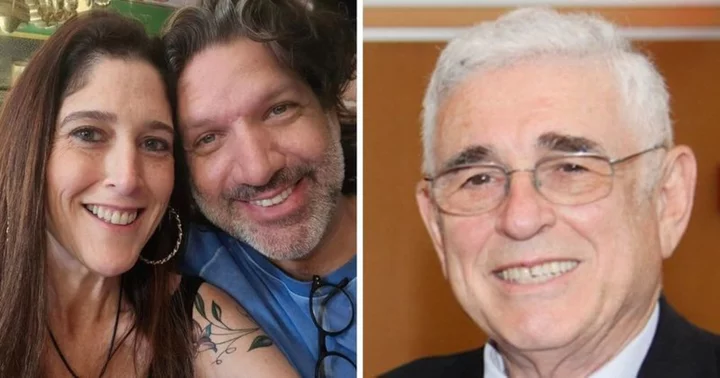

Another arrival in Krasnopillia, Sergiy Guts-Zasulsky, 57, came from the Donetsk region with his partner Tatiana Kachilova and their 12-year-old son.

As the grey-haired man in a black leather jacket spoke, he periodically buried his face in a handkerchief.

"Sorry, it's emotions," he said.

When they walked across and saw Ukrainian flags, "I felt great joy in my soul," he said.

"You think: 'Lord, have all those torments really ended and I'm home?'"

- 'Tourists' or 'stooges'? -

He said he had been beaten and imprisoned by occupying authorities.

"They took me and for a month they held me in a cellar, and I didn't know why. I only realised later it was because I'm Ukrainian," he said.

"They messed around with me," he said. "They damaged my right eye, I can see with it, but barely."

He and his partner Kachilova, 50, said it had become impossible to find work or even call an ambulance without a Russian passport.

Ukrainian-language radio stations were also jammed, Sergiy said.

Kachilova insisted they would not return, saying: "Once was enough for us.That's it. We learnt what Russia is, how it treats people."

Yevdokiyenko and Guts-Zasulsky said Russian border officials had asked why they were going to a country run by "tyrants" and praised Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Others were only visiting Ukraine: to collect pensions, get medical treatment or visit relatives.

Some referred to these negatively as "tourists" or "stooges".

"Someone may have an elderly mother or father who is sick and they can't leave," noted Pluriton director Katerina Arisoi.

"The percentage of such people (out of those arriving) is not large," she added.

To return to Russian-controlled territory, they have to go back via Europe.

Valentina, a 55-year-old former primary teacher from Lugansk region, said she and her husband would return after checks on his heart in Kyiv.

"We can't find a good cardiologist at all, practically all the cardiologists have left (occupied areas)," she said.

Her house keeps her in occupied territory, she said, as well as a bed-ridden sister.

Sumy border guards spokesman Roman Tkach stressed the border with Russia remains officially closed.

But since Russia began letting people through, Ukraine is obliged to accept its citizens.

"Every day we note about 60 to 120 people returning to Ukraine. These are all citizens of Ukraine," he told AFP.

Crossing on foot is safer than taking a vehicle that could come under fire, he added.

"Every day, the enemy is shelling the border territory of Ukraine."

No one making the crossing has been fired on, he said.

Reportedly the corridor is also used to exchange military dead and POWs.

Ukraine never confirms such locations, a spokesman for the Ukrainian office responsible for POWs told AFP.

am/cad/bp