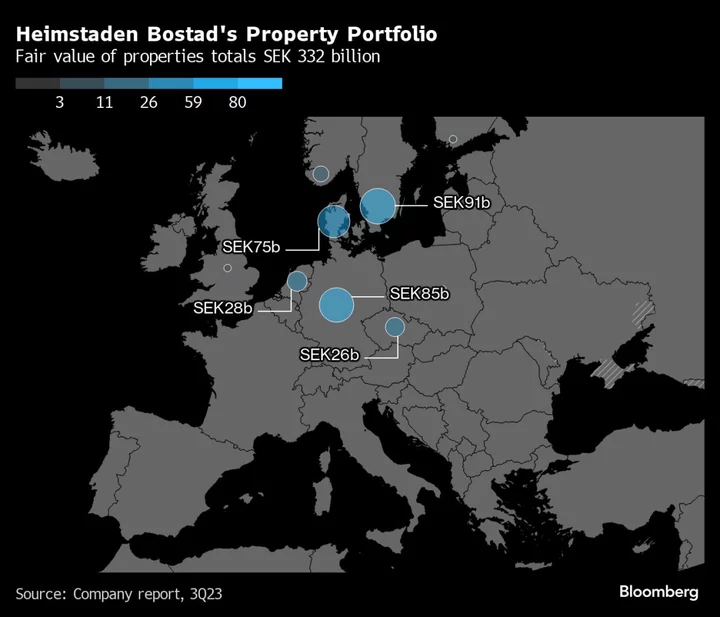

The funding crisis engulfing Sweden’s property sector is prompting the billionaire founder of Heimstaden Bostad AB to look at selling part of his stake in the company, which owns 160,000 homes in nine European countries.

In his first major interview with English-language press in a decade, Ivar Tollefsen said the sale would come in the form of shares held by Heimstaden AB, a property investment firm that he owns through a company called Fredensborg AS. The group, which has a 38% stake in Heimstaden Bostad, one of Europe’s biggest landlords, last sold some of its shares in March, raising about $306 million from existing owners and the UK-based Greater Manchester Pension Fund.

This time around, said the 62-year-old Norwegian, “the buyers will most likely be institutions with a long-term strategy to invest in European residential real estate.”

Against a backdrop of surging interest rates, the group has also begun selling off homes one-by-one to private buyers. At the start of September, Deputy Chief Executive Officer Christian Fladeland said the company had sold 70 apartments primarily in the Netherlands and Denmark at a 47% increase over book value. Heimstaden Bostad has pledged to offload properties amounting to 20 billion Swedish kronor ($1.8 billion) by the end of 2025.

The aim of the plan is “to create as high shareholder returns as possible, selling single units where the market value is higher than we have in our books,” Tollefsen said from his company’s newly renovated office in Oslo, located in what was once the US embassy.

While the asset sales aren’t primarily about deleveraging, the billionaire noted that they would have “positive spillover on credit metrics,” such as the company’s loan-to-value and interest-coverage ratios, “while also reducing dependency on refinancing future debt maturities.”

Such divestments and the possible stake sale mark a significant change of direction for a company built on expansion.

Born into a working-class family outside of Oslo, Tollefsen dropped out of high school to become a successful DJ, eventually parlaying that into an events and DJ services business. His first foray into real estate was in the Norwegian capital, financed in part by the proceeds from a book he wrote about skiing across Greenland. It was the early ‘90s, and Norway’s property market was in a slump.

“My first property was in Fredensborg,” he recalled, referring to the area of Oslo that would later give his holding company its name. Nine years after renting an office there, he bought and renovated the building it was in, becoming “the proud owner of 20 apartments.”

Over the following years, Tollefsen laid the groundwork for what would become one of Europe’s biggest residential property portfolios, taking a hands-on approach that sometimes involved shoveling snow and checking on light bulbs. To expand quickly, he told Bloomberg, he focused on “buying undervalued properties that we could renovate and optimize, for example by increasing the number of bedrooms through moving kitchens into living areas.”

Tollefsen’s empire as it exists today came into being in 2013, after the German bank that had been financing his properties went into liquidation. “We wanted to take out the refinance risk early,” he said, explaining why he decided to partner with the retirement vehicles of Ericsson AB and Sandvik AB alongside Alecta, Sweden’s largest pension fund, on a new project. Together, the four became the first shareholders in the Malmo-based joint venture Heimstaden Bostad.

This arrangement, Tollefsen reflected, “made it possible to grow the company faster than the profit we created ourselves could allow us to.”

Since then, Heimstaden Bostad has enjoyed meteoric growth and Tollefsen has become one of Norway’s wealthiest people, amassing a fortune estimated to be worth about 20 billion Norwegian kroner ($1.8 billion) in 2023, according to Norwegian finance magazine Kapital. Alecta has invested a total of about $4.5 billion into the group, its largest single holding.

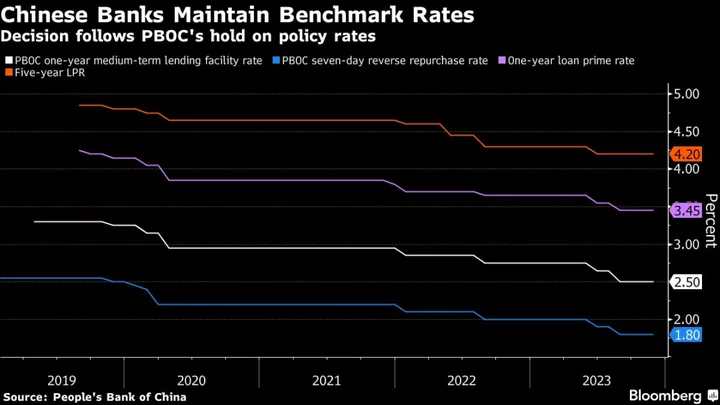

But the sector’s fortunes changed in the spring of this year, when Swedish landlord SBB was downgraded to junk and the country’s real estate crisis became official. A jump in the policy interest rate from zero to 4%, combined with falling real estate valuations, squeezed the nation’s landlords and continues to do so. Months later, many are still scrambling to find alternative ways to refinance or repay $24.6 billion of expensive bond debt maturing between now and 2025, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Heimstaden Bostad hasn’t been immune to these headwinds. Credit rating firm Standard & Poor’s threatened a one-step downgrade of the company to BBB- at the end of last year if its credit metrics weaken beyond their forecasts. The landlord’s most recently reported interest coverage ratio — a snapshot of profit in relation to the amount of debt interest due — fell to 1.8 times, level with S&P’s threshold for the rating.

Even though a possible rating cut would bring the company only one step above junk — where bonds are much more expensive to finance — Tollefsen isn’t fazed by that possibility. While the board has stated its intent to keep its current credit rating, one notch lower “will work well for us as a company and is a rating level we are well familiar with from previously,” he said.

Looking ahead, Tollefsen is upbeat about the prospects for residential property markets as cities continue to expand and purchasing power increases. “Residential will be in demand forever and the most attractive residential assets today look very similar to what they did 100 years ago,” he said. “It’s much more comforting to be in the part of the property market that is experiencing structurally growing demand.”

This stands in contrast, he added, to the commercial property sector. That corner of the market “can over time be decimated by digitalization and requires significant running capex to maintain its relevance,” he explained. When it comes to office space, “a company wants smaller offices if it can get away with it.”