Citigroup Inc. spent 16 months preparing its Banamex unit for a sale that ultimately fizzled after meddling by Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador.

Representatives of the US bank and German Larrea’s Grupo Mexico SAB had spent months preparing the final touches on a $7 billion deal that would have allowed the mining magnate to acquire most of Banamex. Financing was arranged and press releases were written. All that was needed was Larrea’s official sign-off.

Lea la nota en español.

Then AMLO, as the Mexican president is known, took one step too far.

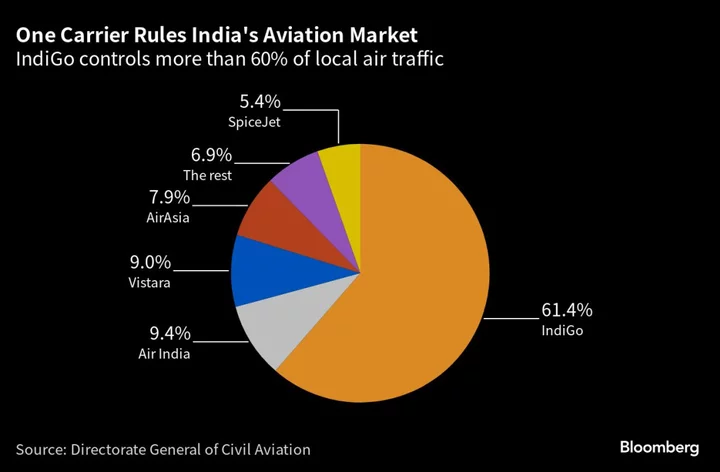

In a move that shocked Mexico, the president seized a section of Grupo Mexico’s railroad tracks in the state of Veracruz. Declaring the property “of public utility,” he transferred it to a government entity. It wasn’t a one-off. Just weeks earlier, AMLO had introduced a set of bills that would extend the state’s reach into aviation and mining.

Taken together, the unprecedented moves spooked Larrea into privately seeking assurances that the banking industry wouldn’t be next, asking whether similar moves might be attempted after the Banamex deal closed, according to people familiar with the matter.

Reassurance was slow to come, and so Larrea dragged his feet on signing a deal, the people said. Then, earlier this week, AMLO teased that he was weighing a public-private partnership for Banamex, a move that added even more uncertainty to Larrea’s ability to pull off the bid. When Citigroup executives came to him with an ultimatum — sign on the dotted line or they would have to move forward with an initial public offering — Larrea told them to do whatever they had to do.

And so, Citigroup announced Wednesday it would go ahead with an IPO for the business, an option that was always on the table but one executives favored less because it would take longer.

“Reality is, it takes at least two to strike a deal,” Susan Roth Katzke, an analyst at Credit Suisse Group AG, said in a note to clients.

Finding a buyer didn’t seem as tricky a year ago, when Citigroup Chief Executive Officer Jane Fraser began the sale process. Bidders including Spain’s Banco Santander SA and the billionaires Carlos Slim and Ricardo Salinas began lining up. With some $44 billion of assets up for grabs, they were lured by the prospect of owning the country’s second-largest bank, with roots dating back 130 years.

But from the beginning, AMLO made his preferences known for how any sale should proceed. The left-wing president had publicly called for a local, rather than foreign, buyer and required there be no massive layoffs in the aftermath. He also wanted to preserve the historically important art collection that Banamex owns.

Even on Wednesday, after Citigroup had declared it would pursue an IPO instead, AMLO mused that Banamex “could represent a good opportunity” for Mexico to own a bank, with the government spending perhaps $3 billion for a stake in the company.

Citigroup — which has long said its continued investment in Banamex was proof of its belief in the country’s prospects — still faces the thorny task of separating the institutional business it plans to keep operating in Mexico from the retail unit it’s dumping. On the plus side, the IPO option allows the bank to resume share buybacks this quarter. They had been on hold because the sale was expected to temporarily hurt capital levels.

“We concluded the optimal path to maximizing the value of Banamex for our shareholders and advancing our goal to simplify our firm is to pivot from our dual-path approach to focus solely on an IPO of the business,” Fraser said in a statement Wednesday.

The Weill Era

When Citigroup announced it would acquire Grupo Financiero Banamex-Accival in 2001, it was instantly heralded as a landmark deal for the country in the wake of the devastating “Tequila Crisis” of the mid-1990s. At the time, analysts said the $12.5 billion price tag was equal to all foreign direct investment in Mexico.

Back then, Citigroup was led by Chairman Sanford Weill, who spent years assembling a collection of Wall Street and consumer-finance businesses that helped solidify the lender’s spot as the the largest financial institution in the world.

Flash forward two decades and Fraser was just a few months into her tenure when she announced in April 2022 that the company would dispose of 13 retail-banking divisions around the world as part of her push to simplify Citigroup and focus on more-lucrative businesses. One division was notably missing from the list: Banamex.

At the time, the New York-based bank was adamant that it had the proper scale to compete effectively in Mexico. Indeed, the unit was home to the company’s largest network of retail branches.

Still, less than a year later, Fraser did an about-face, announcing Banamex had ultimately fallen victim to the CEO’s drive to improve efficiency. At the time, Citigroup said the unit had roughly $44 billion in assets and consumed about $4 billion in average allocated tangible common equity.

The Mexican bank Grupo Financiero Banorte, Banco Santander, Banca Mifel and billionaire Carlos Slim’s Grupo Financiero Inbursa SAB all indicated interest or submitted bids.

But one by one, all of those lenders dropped out or were told by Citigroup they would no longer be moving forward in the process. And Wednesday’s announcement nixed the only remaining bidder.

Now Citigroup’s task will be to successfully manage Banamex during the next two years as it prepares for the IPO. Meantime, “it’ll be open season on Banamex’s market share for a long, long time,” Barclays Plc analyst Gilberto Garcia said in a note.

Also on Citigroup’s to-do list: Separating out its institutional and private-banking services in Mexico. It expects that work to be completed in the second half of next year, allowing an IPO to take place in 2025.

That means the offering will probably take place after AMLO is scheduled to leave office.

(Updates with comment from Barclays analyst in the 21st paragraph.)