Expectations are growing that China’s government will boost spending, especially on infrastructure, as part of a broader stimulus push following the central bank’s interest rate cuts.

Authorities may increase the quota for local government special bonds, allowing them to borrow more to finance infrastructure investment, according to economists from Nomura Holdings Inc. and Standard Chartered Plc. It’s possible the central government could also issue special sovereign bonds, as it did in 2020, or use state policy banks to boost lending in the economy.

Any fiscal support may be limited, however. High levels of debt among local governments and financial turmoil faced by property developers have kept officials cautious in their approach so far.

“They need to do more fiscal, but how major, that is up to a judgment,” Wang Tao, chief China economist at UBS Group AG, said Friday in an interview on Bloomberg TV. She said, though, that “they could increase spending for infrastructure through funding support” for local governments.

Beijing is shifting to a more supportive policy stance to bolster an economy that’s had a marked slowdown since an initial post-reopening surge. The central bank cut interest rates this week for the first time in 10 months, with economists predicting more easing in the rest of the year.

The State Council is now considering a broad package of support measures for sectors including property, Bloomberg News reported earlier this week. Officials at the commerce and economic planning ministries also hinted at possible incentives to boost consumption, including on cars and household appliances.

The Economic Daily also said in a front-page commentary on Thursday that China needs to take further steps to support the economy, including maintaining strong fiscal spending.

The economy’s downturn and worryingly low business confidence levels may have prompted a rethink for authorities who have been wary about overdoing fiscal support. Senior officials have held several meetings with business leaders and economists recently to seek advice on how to revitalize the economy, according to people familiar with the discussions.

“China has plenty of room to boost stimulus if it so chooses,” Michael Hirson, China economist at 22V Research LLC and a former US Treasury attache in Beijing, said in a note Thursday. “The key obstacles are concern over financial risks and the reluctance so far to leverage the central government’s balance sheet to expand fiscal stimulus.”

Broad government spending has slowed this year. Local governments have moderated their pace since May on issuing special bonds, which are a main source of infrastructure project funding. A total of 2.1 trillion yuan ($294 billion) worth of such bonds have been issued so far this year, below the 3.3 trillion yuan sold in the first six months of 2022, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

Nomura expects Beijing to add an extra 500 billion yuan issuance quota for local government special bonds, which would bring the total quota this year to 3.85 trillion yuan. A total of 4 trillion yuan worth of new special bonds were issued last year, according to data compiled by Bloomberg.

The central government could also issue special sovereign bonds and increase policy bank lending, according to Nomura. China sold 1 trillion yuan of such bonds in 2020 to pay for measures to fight the pandemic, and deployed 740 billion yuan through policy bank financing to investment projects last year.

Government agencies are hinting at more targeted support as well.

China will roll out measures to promote the growth of industries including automobiles, home appliances and catering, commerce ministry spokeswoman Shu Jueting said Thursday. Policies to boost consumption — including encouraging more car purchases and building more electric vehicle charging stations — are also being worked on, National Development and Reform Commission spokeswoman Meng Wei said Friday.

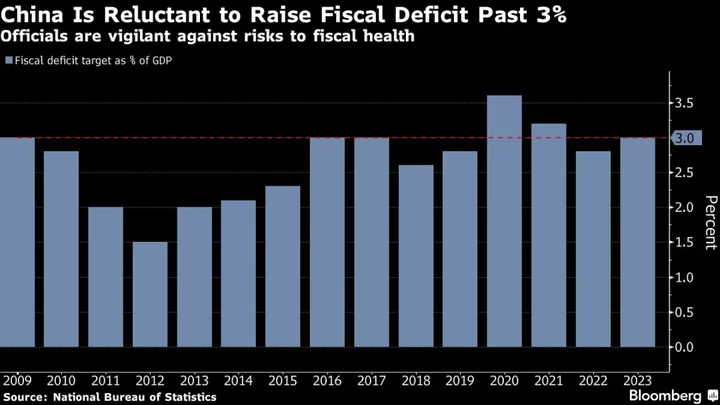

The government has largely stuck to its tradition of keeping the fiscal deficit target within 3% to ensure fiscal health, only breaching that level in 2020 and 2021. That principle has been criticized by opponents, though, as unnecessarily restrictive over the government’s support for the economy.

“The government seems very reluctant to spend more on-budget money as a way to lift growth,” said Tianlei Huang, China program coordinator at the Peterson Institute for International Economics. “There are resources available for the government, both central and local, to draw on and increase spending if they really care about restoring growth.”

--With assistance from Jing Li and David Ingles.