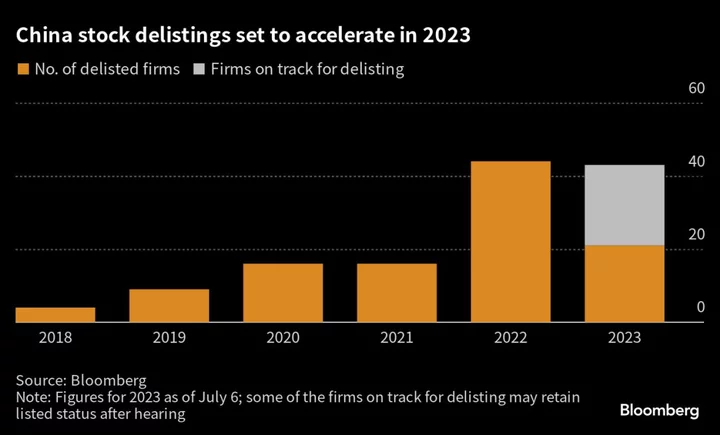

China is on course to see a record number of stocks being delisted from its exchanges this year as new rules introduced to improve the quality of listed companies snare an ever greater number of victims.

A total of 21 firms have already lost their listed status on the Shanghai and Shenzhen bourses since the start of January, while another 22 have said they are at imminent risk of being culled, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. The potential total almost matches the all-time high of 44 set in 2022, even though the current year is only half way through.

Chinese regulators revamped delisting guidelines in 2021 as part of their efforts to clean up the stock market and bolster investor confidence. The number of delistings jumped the following year, and has risen further in 2023 as the economic recovery from the pandemic has faltered.

“A macro slowdown, weak market sentiment, and expanded IPO reforms are all factors behind the delisting and optimization of stocks in the market,” said Yang Ruyi, a fund manager at Shanghai Prospect Investment Management Co. The rise in delistings is adding to speculation that other stocks with poor fundamentals will also lose their listing status, she said.

While the pace of delistings has sped up this year, the total is still less than 25% of the number of IPOs. China’s stock exchanges welcomed nearly 200 newcomers in the first half — more than any country in the world — swelling the combined sum of listed firms on the two exchanges to more than 5,000.

Here are some additional Q&As about the surge in delistings:

Why were the tighter delisting rules introduced?

The new rules that took effect in 2021 expanded the criteria for possible delisting, and sped up the process of weeding out weaker listed companies. The main intention was to help encourage the listing of new and innovative companies under easier IPO rules. Among other reasons, regulators have signaled that a stronger capital market is critical toward gaining an edge in the tech race with the US.

What exactly are the current delisting criteria?

Delistings can be brought about in three main ways: trading levels, poor financials or illicit behavior.

In the trading category, the key triggers include having fewer than 5 million shares changing hands for 120 sessions; a close below 1 yuan for 20 sessions; a market cap below 300 million yuan ($41 million) for 20 sessions; or a company having fewer than 2,000 stakeholders for 20 sessions.

The financials category includes revenue below 100 million yuan coupled with a net loss; a net liability in the past year; an auditing firm issues an “adverse opinion” or “disclaimer of opinion” on its annual report; or certain types of administrative punishments from the securities regulator.

What are some of the large firms that were delisted this year?

Among the bigger companies that have lost their listings this year are Sichuan Languang Development Co., which was removed last month after triggering the 1 yuan rule. Bluedon Information Security Technology Co. is also on track to delist, after it reported a net loss and a revenue less than 100 million yuan and announced a net liability.

Have some sectors been affected more than others?

Property firms have seen the most delistings, which isn’t surprising given their current financial stresses.

Investor sentiment toward the sector has worsened despite additional support from the authorities. In addition to those already delisted, Yango Group Co. is also facing imminent removal after triggering the 1 yuan rule, pending a final hearing from the exchange. Approximately a dozen others are below or close to that level.

What happens to shares and investors after a delisting?

Delisting rules stipulate that some firms heading for the exit to enter a final 15-session “organization period,” during which they must issue regular warnings alerting investors of risks ahead of the final trading day. The stock isn’t subject to trading limits on the first day of the final phase.

After delisting, investors still own equity in the company. The difference is that they can no longer trade them in the secondary market in Shanghai and Shenzhen. Shareholders may seek to dispose of their holdings at a special corner of the National Equities Exchange and Quotations system, an over-the-counter market with relatively low liquidity.

What does this mean for investors going forward?

The investment strategy of buying the worst-performing shares in hope of a restructuring, a back-door listing or a similar turnaround story is fast being consigned to history. That doesn’t mean this is the end of speculative plays in China’s retail investor-heavy stock market, but it will help increase the shift toward fundamentals-driven investing.