Foreign investors are losing interest in China, and hedge funds that target the world’s second-biggest economy are paying the price.

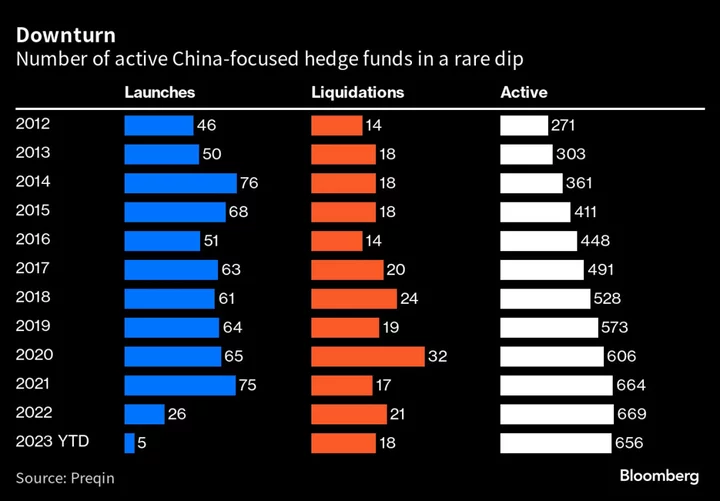

The number of active China-focused hedge funds has slipped for the first time since at least 2012, with only five new funds launched this year as of June, according to data from Preqin Ltd. Another 18 funds were liquidated, the data show.

The contraction marks a major shift for offshore China hedge funds, which accounted for almost half of new funds in Asia as recently as 2021 as investors sought to ride the wave of the once high-flying economy and capital markets. Beijing’s crackdowns on private companies in industries including after-school tutoring and e-commerce, along with growing geopolitical tensions with the US, have led to weak returns since then and sapped global investors’ appetite for China assets.

“We definitely see less demand for China managers from both Asia and foreign investors,” said Otto Chan, head of portfolio management at Persistent Asset Partners Ltd., a 21-year-old fund of hedge funds firm.

Dantai Capital Ltd. shuttered its flagship Greater China hedge fund this year after concluding its investment strategy no longer worked in the current market environment. Tiger Management LLC-backed Yulan Capital Management also liquidated an Asia hedge fund focused on Greater China in late 2022, according to a newsletter.

China-focused hedge funds — stock pickers in particular — are facing an unprecedented second consecutive year of losses, according to Eurekahedge Pte data. More than two-thirds of China-focused hedge funds lost money in 2022, while 36% were down a fifth or more. In the first half of this year, 62% of China funds failed to make money, Preqin data showed.

China’s economic recovery is losing steam despite Beijing’s recent policy support, while geopolitical tensions with the US are showing little signs of letting up.

Managers put on a brave face in public, touting the country’s long-term growth potential and cheap valuation. In private, they bemoan the end of offshore China hedge funds, those that raise money from international investors to trade securities related to the country, said one of them.

Legends China Fund dropped 16% in the first seven months of 2023, after more than 20% losses in each of the last two years, according to a newsletter and a person with knowledge of the matter, who asked not to be identified discussing private information. Blue Creek China Fund was down 17% in the first half, struggling to end a losing streak that began in 2021, according to its June newsletter.

A representative for Legends declined to comment. Blue Creek didn’t reply to emails seeking comment.

Certain shared characteristics of offshore China funds made them particularly vulnerable to the latest regulatory and geopolitical headwinds.

Some 88% of the 417 China-focused hedge funds in Bloomberg’s database specialize in equity long-short, or taking bullish and bearish wagers on stocks. Out of those, two-fifths are long-biased. The strategy tends to fare better when the market is in an upswing. Many focused on investing in tech and e-commerce stocks.

Greater China equity long-short funds were down about 1% through July, with 11% reporting their figures, according to Eurekahedge.

The MSCI China Index has dropped 43% since the end of 2020, versus a 19% gain for the US S&P 500 Index over the same period.

Investors are seeing more political risks for their China investments and have become less confident about the long-term economic upside, said William Ma, global chief investment officer of GROW Investment Group, a Shanghai-based asset manager backed by Julius Baer Group Ltd.

Some investors who have been hurt by their China exposure for two years are waiting for a market rebound to reduce their holdings. With North American pensions scaling back existing allocations or putting future plans on hold, other investors are wary of being caught in the path of these outflows, said another long-time investor in Asia hedge funds, who asked not to be identified because of the political sensitivity of such comments.

Shifting Tactics

Facing this existential crisis, China managers are trying to adapt.

In the last three years, APS Asset Management Pte, which oversees $2.1 billion in China long-short and long-only strategies, has seen tepid interest from North American backers, especially among the public pensions, said President Ken Chung.

The Singapore-based company has in recent months redirected capital raising efforts to include the Middle East and South Africa. In the first half, it scored its maiden investors from these two geographies.

“We’ve grown up in a world where it’s a US-led global world order,” Chung said. “Going forward, it will be a two-sun solar system. One is US-led, one is China-led. And there will be planets that revolve around either one.”

Some managers who previously targeted international investors are pivoting toward a domestic audience, pitching funds that will trade regional or even stocks globally, said GROW’s Ma, declining to identify the firms.

As supply chains diversify away from China, others are touting their edge in a so-called “China+1” strategy. That involves tapping into the trend of Chinese companies building production facilities in places including Cambodia and India, or expanding sales outside of China and US markets, Ma said.

Certain past investment approaches such as momentum trading will have to change, said Chris Wang, chief investment officer of Yunqi Capital Ltd. in Hong Kong.

The “extremely high risk premium” investors attach to the China market may put company fundamentals, corporate governance and shareholder returns in the spotlight. The largest profit contributor to his China fund last year was TAL Education Group, which was sitting on cash levels that were twice as high as its market value when he built his stake, Wang said. His largest bullish bet now is on Qifu Technology Inc., which has been handing back half of its earnings to investors through dividends and share buybacks.

“Companies are sitting on a lot of cash. Investment opportunities and returns are not as attractive as they used to be,” he said. “So it’s logical to boost investor payout. It’s clearly going to be a major trend in the next five to 10 years.”

--With assistance from David Ramli.