China suspended publishing data on its soaring youth unemployment rate to iron out complexities in the numbers, fanning investor fears about data transparency in the world’s second-largest economy.

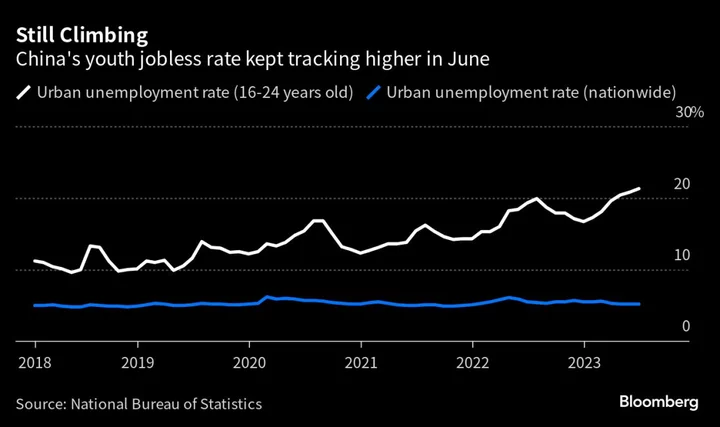

The National Bureau of Statistics didn’t release a figure for the jobless rate for people aged between 16 and 24 in its July economic activity report on Tuesday. Youth unemployment hit a record 21.3% in June, with the bureau last month indicating the figure would probably increase.

Fu Linghui, a spokesman for the NBS said the labor statistics need “further optimization,” and more research needs to be done on “whether students looking for a job before graduation should be counted in the labor statistics.”

The move is the latest example of how President Xi Jinping’s government is limiting access to information in order to more closely guard data it deems sensitive and manage the narrative about the weakening economy.

China has over the past year limited access to corporate data, court documents, academic journals and raided expert networks serving businesses, hampering investors’ ability to assess the economy. Officials have also been downplaying economic risks like deflation, with some Chinese-based analysts saying they were instructed by regulators and their companies not to discuss the matter publicly.

“The decision to stop publishing youth unemployment data will not help with international investor sentiment, as it entails a deterioration in visibility,” said Carlos Casanova, senior Asia economist at Union Bancaire Privee. He had forecast the youth jobless rate to reach 22% in July, although the omission of the data suggests the actual figure was probably higher than that, he said.

The youth unemployment data is politically sensitive for a Communist Party obsessed about maintaining social stability. Nationwide protests last year against strict pandemic rules were led by students, with some calling for Xi to step down.

Economists said the omission of the youth unemployment data suggests officials are concerned about negative sentiment spreading through the country.

“Authorities clearly recognize this is a confidence crisis and are trying to also ensure the messaging is not overly bearish,” said Louise Loo, an economist at Oxford Economics. “But if they had published, it’s almost certainly to have edged higher again, possibly peaking only in October.’

Youth unemployment has soared since last year, a sign of a weakening economy as employers pull back on hiring, but also lingering effects from the crackdown on the technology sector, once a lucrative industry for many young people.

Summer usually sees a jump in the youth rate as tens of millions of graduates hit the labor market. The government had previously said almost 12 million students from universities and colleges would graduate in 2023.

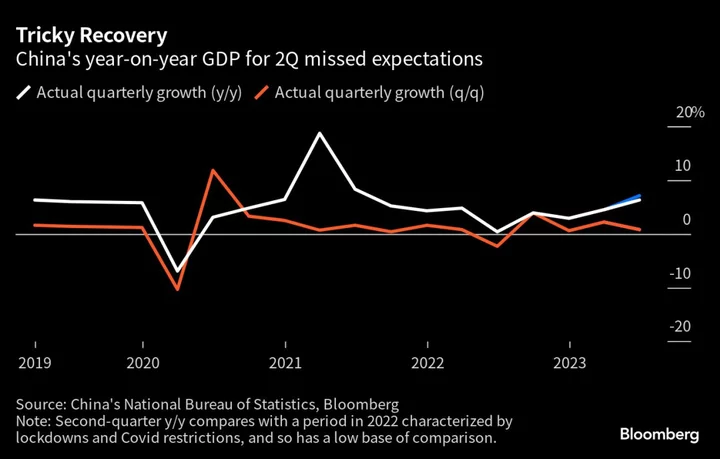

The NBS figures on Tuesday showed a weakening in the labor market, with the urban jobless rate rising to 5.3% in July from 5.2% in June, and a slowdown in economic activity. Shortly before the data, China’s central bank unexpectedly reduced a key interest rate by the most since 2020.

Gary Ng, senior economist at Natixis, said omitting some of the jobs data would make it harder to understand China’s youth employment landscape, an “important” indicator given the nation’s current economic pressures.

“Still, if the discontinuation is to improve the statistical methodology,” then the damage to investor confidence would depend on “whether the new data series can provide a better picture,” he added.

--With assistance from James Mayger.

(Updates with details from second paragraph.)