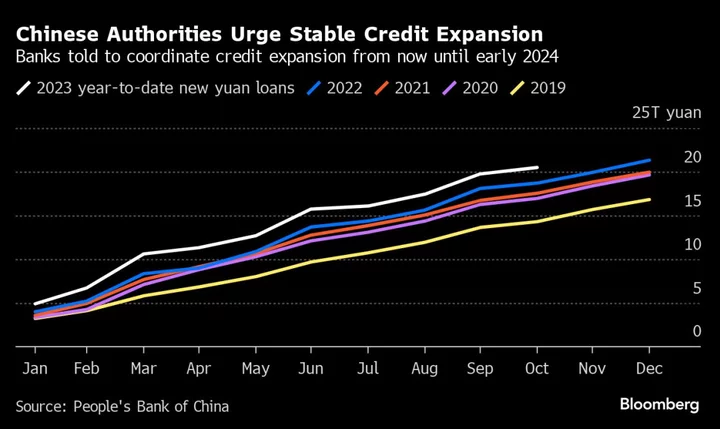

China’s central bank has encouraged lenders to cap the amount of new loans they issue in early 2024 and shift some forward to this year as authorities try to smooth the credit cycle, people familiar with the matter said.

The People’s Bank of China last week guided lenders to make sure the value of new loans they extend in January-to-March does not exceed the quarterly average issued over the past five years, said the people, asking not to be identified discussing a private matter. The guidance from the PBOC implies a limit in the first quarter of 7.9 trillion yuan ($1.1 trillion) in loans, according to Bloomberg calculations — a quarter less than the amount in the first three months of 2023.

Banks will also be given incentives to move forward some of the lending projects to the final months of this year, the people said. The plans may be adjusted based on the economy’s performance, they added.

The People’s Bank of China didn’t immediately respond to a request for comment.

The PBOC guidance comes at the tail end of an erratic year for credit growth. The $56 trillion banking industry has also been contending with shrinking profit margins and rising bad loans after being drafted by authorities to support the economy and curb risks from the property sector and debt-ridden local government financing vehicles.

Evening out the pace of loan issuance may provide more clarity to investors who are sensitive to wild volatility in the numbers and consider loan demand a barometer for the health of China’s economic recovery.

“It’s to smooth out the volatility in loan provision,” said Michelle Lam, Greater China economist at Societe Generale SA, adding that loan growth momentum “is probably weaker than desired” in the fourth quarter, given the weakness seen in October’s data.

Early in the year as the world’s second-largest economy reopened from the pandemic, Chinese banks issued record amounts of new loans as regulators urged them to front-load activity to drive economic growth. But that pace dropped off rapidly over the course of 2023: New loans plunged in July to a 14-year low, rattling markets and contributing to volatility in the yuan and onshore equities.

Some of the ebb and flow comes down to seasonality: Loan growth is usually slow in the final months of the year before banks push to hit their targets in the first quarter of the following year. That’s because the January-to-March period is when those lenders have a lot of loan quota to tap into.

Lending early is also good for profits at a time when banks are getting squeezed at the margins. For China’s biggest banks, net interest margins dropped to a record low 1.74% at the end of the first half of 2023, below the industry’s 1.8% threshold seen as necessary to maintain a reasonable amount of profitability.

The guidance also adds to a slew of steps regulators have taken in recent days to stabilize funding and credit as 2023 comes to a close. On Friday, the central bank and other regulators urged lenders to coordinate credit growth and meet the reasonable funding needs of property firms.

“The PBOC is now focusing on credit policy rather than monetary easing,” said Raymond Yeung, chief economist for Greater China at Australia & New Zealand Banking Group Ltd.

While China seems now to be in little danger of missing a full-year government growth target of about 5% for this year, focus has begun turning to 2024 and how to best sustain the economy’s momentum. On Monday, Chinese Premier Li Qiang told officials to boost financial support for the economy during a central financial committee meeting.

The real estate sector continues to be a major drag on the economy, leading the government to step up support — including via drafting a list of 50 developers that would be eligible for improved financing, Bloomberg News reported this week. Earlier, Bloomberg reported that China also plans to provide at least 1 trillion yuan worth of low-cost financing to certain affordable housing programs to help the market.

The property-related support is “increasingly similar to the reflation campaign at the end of 2015,” Yeung said, referencing a period when the PBOC made use of support including cheap, targeted policy loans to reverse a property downturn. This time, Yeung said, authorities seem to be adopting a “cross-cyclical” approach, meaning they’re considering the economy’s performance over a longer period of time.

“If credit growth is deemed too large, they will guide banks to tighten” in the first quarter of 2024, he added.

There’s other major stimulus in the works, too. Last month, policymakers made a rare mid-year revision to the budget and approved 1 trillion yuan ($138 billion) worth of sovereign bonds for infrastructure investment.

(Updates with analyst commentary.)