Brazil’s senate approved a provisional measure establishing the structure of President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva’s cabinet, a relief for the leftist leader whose government was nearly thrown into chaos.

Senators passed the bill in a 51-19 vote Thursday, paving the way for a modified version of the temporary measure Lula used to establish a bevy of new ministries to become law before it expired at the end of the day. The lower house of congress approved the legislation in a 337-125 vote late Wednesday night.

Lula launched a last-minute effort to secure its approval Wednesday, calling emergency meetings with political allies and lower house Speaker Arthur Lira a day after a planned vote was delayed. Had the measure expired, 14 of Lula’s 37 ministries — including his departments of Planning, Racial Equality, Indigenous Peoples, Culture and Industry — would have shuttered, putting priority elements of his agenda and his ability to accommodate a range of political allies at risk.

Although he avoided that outcome, the measure’s approval required significant concessions: The version that passed curbed some powers of Brazil’s Ministry of Environment, changes that will test Lula’s commitment to the green agenda he has pledged to pursue.

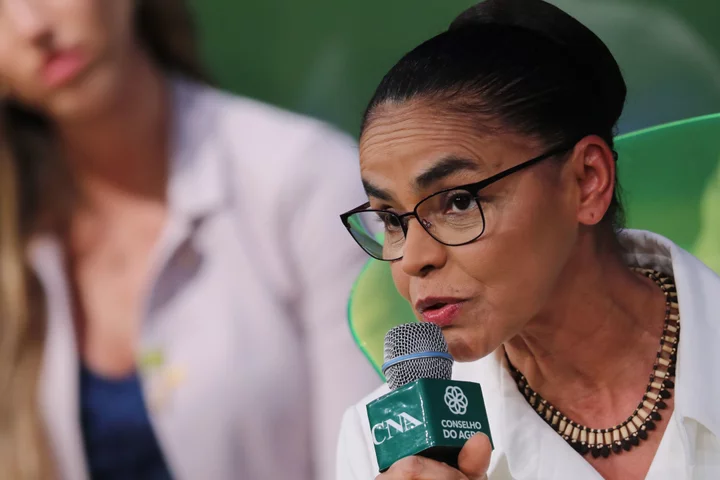

The alterations transfer some authority from the ministry and its leader, Marina Silva, to other government bodies, including the administration of a database that tracks environmental information and inspections to prevent deforestation on rural lands.

“Congress has no obligation to approve everything that I want,” Lula said during a press conference after the Senate vote Thursday. The negotiations over the measure, he said, are “the nature of politics.”

Congress on offense

The modified measure is part of a broader offensive from congress, where conservative parties and an influential agribusiness caucus pose the biggest threats to the environmental ambitions Lula outlined during his 2022 campaign, and that have attracted significant international support early in his presidency.

Lawmakers had already loosened some rules in ways that environmental experts say will lead to more deforestation. On Tuesday, they voted to place additional restrictions on the creation of Indigenous territories, approving legislation to limit the demarcation of new protected areas to lands tribes occupied when Brazil’s constitution was adopted in 1988.

Read More: Brazil’s Bet on Oil Growth Suffers Setback Amid Climate Push

The pushback from congress is taking place amid another clash that has divided factions of Lula’s government.

In May, Brazil’s environmental authority, Ibama, blocked state-owned oil giant Petroleo Brasileiro SA’s plans to explore an offshore frontier at the mouth of the Amazon River, a site known for its coral reefs and diverse marine wildlife. Ibama is currently reviewing the decision, which Marina Silva has defended amid protests from Petrobras and some members of the president’s governing coalition.

Some Lula allies say his opponents in congress are seeking to exploit those differences to drive a wedge between the president and Silva, who has served as the face of the government’s environmental agenda both within Brazil and globally.

The pair has split before: In 2008, Silva left her role as environment minister during Lula’s previous presidency amid disagreements with his government’s policies. But Silva has said that she and Lula are on the same page now, and that the president still considers the environment a major priority.

‘We will resist’

She has instead taken aim at congress, arguing that its plans will negatively affect Brazil’s image on the world stage, where Lula’s pledges to reverse rising levels of deforestation have won him acclaim and convinced nations like the US and UK to promise funds for Amazon rainforest protection.

The international community, Silva argued last week, will see the actions in congress as an attempt to force his government to adopt the policies of former President Jair Bolsonaro, whose approach to environmental and climate change issues drew global backlash.

They may also jeopardize a pending trade agreement between the European Union and Mercosur, a bloc of South American nations that includes Brazil, she has warned. France has previously conditioned its support for a deal on improved deforestation and climate policies in Brazil.

“The credibility of President Lula and the Minister of Environment isn’t enough,” Silva said during a congressional hearing last week, after a committee advanced an initial proposal to change her ministry’s powers. “This will close our doors.”

Read More: UK Commits $100 Million to Brazil’s Amazon Fund, Joining US

While Lula ultimately blessed the changes to the structure of his government, potential vetoes of the other measures could provoke a confrontation with congress at a time when he is still struggling to build a solid base of political support.

Other challenges also loom. Brazil’s Supreme Court is considering rules governing the demarcation of new Indigenous territories in a case that may resume on June 7. Before that, the court will decide whether to authorize the construction of the Ferrogrão, a 933-kilometer (580 miles) railroad that would transport grain from the central area of the country through the Amazon region.

Silva pledged to fulfill the government’s environmental promises during a speech in Brasilia, the capital, last week.

“We have to resist, and we will resist,” she said.

(Updates with Senate vote in first two paragraphs, Lula comments in sixth paragraph)