China will likely disappoint those hoping the government will roll out massive stimulus to shore up the weakening economic recovery, said Zhu Min, a former deputy managing director of the International Monetary Fund.

“There are a lot of expectations on the Chinese government to have more stimulus policies. I don’t think this is real,” Zhu said during a panel Thursday at the World Economic Forum’s Annual Meeting of the New Champions in Tianjin, China.

Zhu joins a growing chorus of experts who project the world’s second-largest economy will announce only moderate stimulus this year as the rebound loses steam. Consumer spending has slowed, while confidence among households and businesses is flagging.

The central bank cut policy interest rates this month for the first time since last August, fueling speculation about further support. But officials have been slow to announce any concrete stimulus package.

Zhu pointed to several factors that limit China’s options, including that it “has very high debt already.” The nation’s debt-to-GDP ratio climbed to a record last year as growth slowed. Local governments and property developers are struggling to repay debt, threatening the health of the $55 trillion banking system.

Any policies will likely target structural issues rather than big macroeconomic ones, Zhu said.

“Resource constraints” in China may make big stimulus infeasible, said Keyu Jin, an economics professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science. Jin, the author of The New China Playbook: Beyond Socialism and Capitalism, spoke to Bloomberg News on the sidelines of the same conference this week.

“There’s enough room for stimulus, but the problem is that you need a massive stimulus in the trillions of RMB or more to have a moderate impact on today’s Chinese economy, because the return on the stimulus is much lower,” she said.

The People’s Bank of China is likely to cut policy rates by just 5 basis points in the final quarter of 2023, according to the median estimate in a recent Bloomberg survey of economists. Respondents to that poll also predicted the government would roll out tax breaks for consumers and increase financing for infrastructure investment through state policy banks.

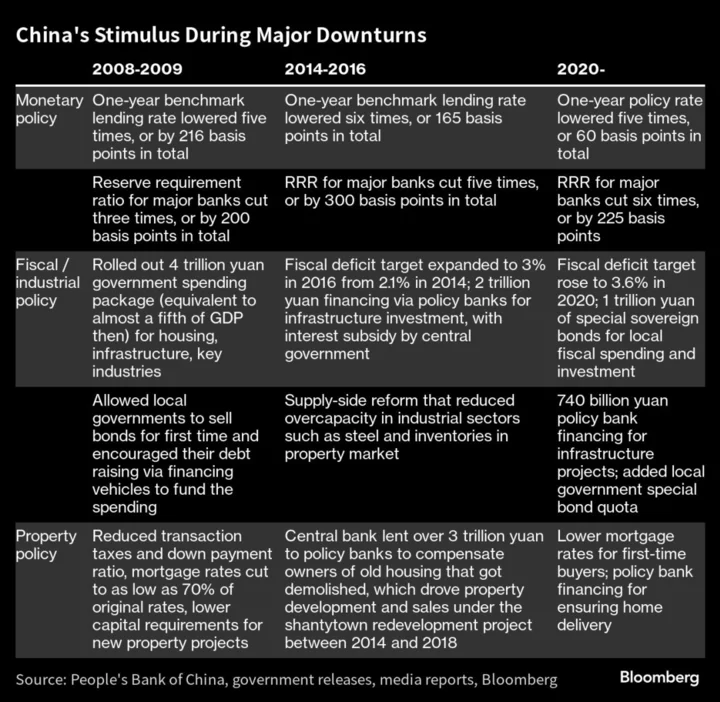

China’s approach to stimulus has been restrained throughout the pandemic as compared to prior downturns. The central bank has cut its benchmark rates in recent years by much smaller degrees than it did during cycles in 2008 and 2014.

Fiscal support was also massive during those periods. In response to the 2008 global financial crisis, Beijing launched a 4-trillion yuan ($552 billion) fiscal package to expand government spending on infrastructure, housing and other projects. The amount accounted for a fifth of gross domestic product back then.

Faced with a property downturn and deflationary pressures starting in 2014, the central bank at that time provided more than 3 trillion yuan in low-cost loans to policy banks for “shantytown redevelopment” projects. Likened by economists to “helicopter money,” that program boosted property sales and construction — but also sent debt and home prices soaring.

Beijing ultimately will need to find ways to fix the confidence gap. Zhu on Thursday urged the government to lift resident income growth above GDP growth this year, while also creating a better social safety net by improving pensions and health care.

“I understand there is a lot of fear,” Zhu said. “We need really to take the fear away, rebuild the confidence. This is the most important thing.”

--With assistance from Lucille Liu.