It hardly required a degree in international relations to comprehend the weighty symbolism at play here on the final day of an unusually consequential Group of Seven summit.

In the same city obliterated by the world's first atomic bomb, leaders of the world's top industrial democracies added a seat at their table for besieged Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky, whose warnings of Russian escalation assumed new significance against the nuclear backdrop of Hiroshima.

It wasn't very long ago that the eighth seat (or actually the tenth, if you count the two representatives from the European Union) was occupied by Russian President Vladimir Putin, who was ejected from the bloc in 2014 following his annexation of the Ukrainian territory of Crimea.

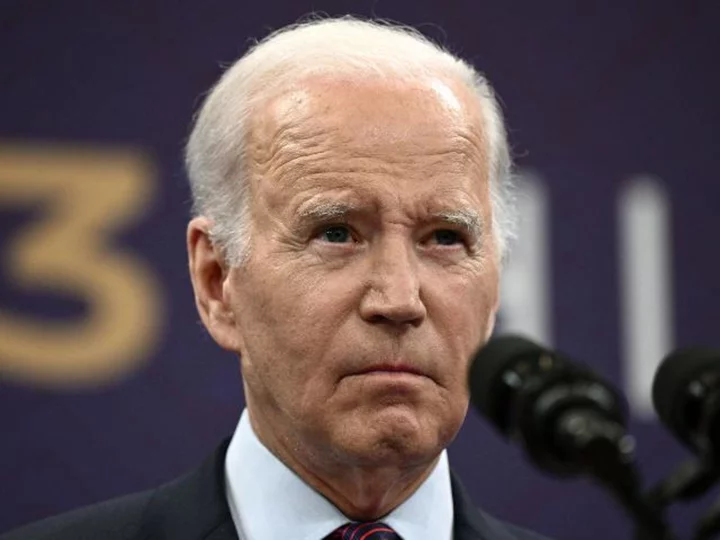

Standing in a line of suit jackets at a photo-op Sunday, Zelensky's military uniform stood out, a reminder of the war that he continues to ravage his country. Walking away, President Joe Biden wrapped his arm around Zelensky's shoulders.

The transformation of the G7 in the decade since Russia was ejected -- and particularly the past two years -- has turned the group into what Biden's top aides call the "steering committee of the free world." With refreshed purpose and an eye on China, no other body has been as effective in coalescing around shared action.

Yet implicit in Zelensky's decision to show up here in person is the lingering fear -- which Moscow is banking on -- that fatigue and political pressure will cause Western support for Ukraine to wane. None of the G7 leaders are particularly popular at home, even as they produce results abroad.

Trump on their minds

Biden's fellow leaders have undoubtedly taken notice, with no small measure of alarm, at statements made earlier this month by former President Donald Trump during a CNN town hall casting doubt on his support for Ukraine and pledging to resolve the crisis in a day.

Trump's potential return to the White House, or the election of another like-minded Republican, has worried Ukrainian and Western leaders alike, according to diplomats and other officials.

After all, it was Trump who had argued over dinner at the 2019 G7 summit in Biarritz, France, that Russia should be allowed back into the group. As the leaders dined on plates of Basque vegetables and red tuna overlooking the Atlantic coast, Trump interjected and asked why Russia should not be included in the talks, given its size and role in global affairs.

He was met with sharp resistance from some of the leaders, principally German Chancellor Angela Merkel and British Prime Minister Boris Johnson, neither of whom remains in power. The exchange on Russia was notable for the fiercely argued views on both sides, shocked officials said at the time.

There is little enthusiasm for that type of summit to return, at least among the leaders and their aides who currently comprise the G7. Whether Trump would even continue attending G7 summits if he returns to the White House is an open question; as president, he repeatedly questioned his team why it was necessary to attend.

That level of chaos was nowhere to be found in Hiroshima this past week, when leaders appeared to generally like each other. Even Biden and French President Emmanuel Macron, whose relationship can be complicated, found themselves arm in arm as they walked away from one of a string of "family photos."

'America is back'

The contrast between the 45th and 46th presidents has never been subtle and is one Biden has sought to elevate and use to his advantage to bolster the cornerstone alliances of US foreign policy.

Through that lens, the gathering in Hiroshima provided a window into the degree to which the aspirational "America is back" proclamations at Biden's first G7 in 2021 have turned into tangible, and often US-driven, outcomes.

While the unyielding unity of the coalition's support for Ukraine was at the forefront, the evolution of the G7's willingness to sharpen both tone and actions toward China is substantial -- even if US officials acknowledge there are areas they'd like to advance at a faster and more robust pace.

The steadily warming relations between South Korea and Japan were put front and center throughout -- an area of intense focus for national security adviser Jake Sullivan.

Though his official visit to Australia was scrapped, Biden's meeting in Hiroshima with that country's prime minister, Anthony Albanese, marked the latest conversation between leaders who have steadily cemented a close relationship viewed as a cornerstone piece of US regional strategy.

But no leader embodies what Biden's top advisers view as the advances they've made in the region more than the host. Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida has driven a dramatic shift in his country's defense posture and capability -- with explicit US support each step of the way.

As one US official put it after Biden effusively praised the strength of the US-Japan relationship: "Not hyperbole."

Fires at home

And yet the same reality that has trailed, or at times threatened to consume, Biden's first two years in office wasn't far from the participants' minds, several aides to G7 leaders said candidly.

Even before Biden left for the G7 summit, the stalemate over raising the federal borrowing limit prompted a scramble to rearrange the president's engagements so he could return to Washington early.

Throughout the trip, Biden made apologies for the situation. His counterparts mostly seemed to understand.

"I would have done exactly the same thing," said Albanese, who was supposed to host Biden in Sydney. "All politics is local, as you and I both understand."

In his meetings with leaders this week, Biden was quizzed on the debt ceiling standoff, which Sullivan, his national security adviser, described as a "matter of interest" among the collective group. He described the tone as more curious than concerned: "This is not generating alarm or a kind of vibration in the room," he told reporters.

But in part, one European official acknowledged, that only served to exacerbate the risk of miscalculation.

"I mean no offense, but we've gotten pretty used to this sort of thing," the official said in reference to the debt ceiling and government shutdown crises that have defined Washington for more than a decade.

Each has resulted in a last-minute resolution, so much so that it has become the baseline expectation. But the official acknowledged there were quiet whispers about whether perhaps this time it was different.

"Well," the official asked with a tinge of trepidation. "Is it?"

Privately, US officials struck a more candid tone -- one that grew more anxious as each day of the summit passed.

"Debt ceiling brinkmanship that Republicans are driving in Washington, DC, undermines American leadership, undermines the trustworthiness that America can bring," a senior administration official said.

Biden provided the most jarring window into the acute -- and different -- risk at hand in his news conference Sunday shortly before heading back to Washington.

"I can't guarantee that they wouldn't force a default by doing something outrageous," Biden said of House Republicans and what that meant for the message he could deliver to his counterparts. "I can't guarantee that."

That can hardly have been reassuring for leaders gathered in Hiroshima, a city scarred with reminders of America's capacity for destruction.

The self-created dysfunction in Washington made for a discordant splitscreen as world leaders met with a survivor of the 1945 bombing and toured the city's museum, where tattered clothing and scorched children's toys served as reminders of that day's horrors. Together, they placed wreaths at the curved cenotaph, its inscription pleading to the world to "not repeat this evil."

It wasn't a mistake that Kishida, who heard stories about the bombing from his grandmother, chose Hiroshima for his summit. Nuclear threats are on the rise, and Biden himself has warned that the risk of "nuclear Armageddon" is at its highest since the Cuban Missile Crisis. It will be the task of the newly marshaled G7 to find a way to prevent it.

Yet as Air Force One departed here Sunday, it a different crisis Biden was trying to prevent, and it was not Pyongyang or Tehran posing the most acute and pressing threat to global stability.

It was Washington, which now has less than two weeks to prevent economic catastrophe.