Indonesia’s growth performance last quarter is poised to top most of its peers in Southeast Asia, but its path ahead is tricky amid widening cracks in the economy after the pandemic.

While its latest gross domestic product print shows a consumption boom that’s hovering near levels a decade before the pandemic, it has largely left behind lower-income households beset by low wages and limited opportunities.

Without the spending on major Muslim holidays that propped up growth in Southeast Asia’s largest economy to 5.2% in the April-June period, economists expect a deceleration to 5% then 4.9% in the next two quarters.

That casts doubt on a region that’s been insulated from the global recession risk because of their strong domestic economies. Neighboring Philippines also reported a sharp slowdown in second-quarter growth as inflation doused revenge spending while Singapore posted slower than initially estimated figures. Vietnam is struggling to meet its target. Malaysia and Thailand have yet to report last quarter’s GDP.

“We are forecasting GDP growth at 4.6% in 2023, lower than the pre-pandemic potential growth of 5.3%,” HSBC Holdings Plc economist Pranjul Bhandari said of Indonesia, citing El Niño, a pullback in state spending and tepid external demand as hurdles. “In fact, we think that a weaker-than-potential growth is likely keeping core inflation at low levels.”

Much of the scrutiny zeros in on the strength of consumption, which powers over half of Indonesia’s GDP.

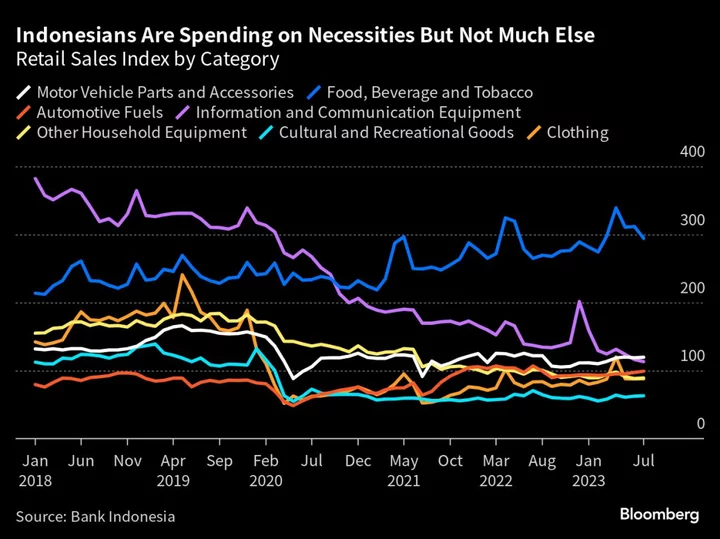

Retail sales have been patchy this year — largely driven by basics like food, beverage and fuel, while discretionary spending has yet to bounce back. Consumer giants like PT Indofood CBP Sukses Makmur, PT Matahari Department Store and PT Unilever Indonesia reported disappointing revenues last quarter.

Consumer confidence slipped to a four-month low in July. The readings are more dire in the lowest income band. Those who spend an average of 1-2 million rupiah ($65-130) a month are barely optimistic about income and job availability, and are pessimistic about their likelihood of purchasing durable goods.

It also highlights the inequality of Indonesia’s post-pandemic rebound, as the economy was already able to regain upper-middle income status this year despite unemployment and poverty remaining stubbornly above pre-pandemic levels.

“The main thing holding consumption back is lackluster wage growth,” said Miguel Chanco of Pantheon Macroeconomics Ltd., expressing some doubts on the credibility of the second-quarter GDP print. “There was a huge slowdown in nominal earnings growth early this year, enough to push wage growth in real terms back into the red.”

Capital Economics wrote after the Aug. 7 data that “growth has slowed sharply over the past year and the economy is expanding at a slower pace than the official figures show,” citing its Activity Tracker.

For Bloomberg economist Tamara Mast Henderson, the recovery in household and government spending last quarter, and faster investment will help tide the economy over.

Without the cover provided by a buoyant consumer sector, Indonesia will have to lean on other growth engines like investment and exports which are contending with borrowing costs at a four-year high and lower global commodity prices.

“All in, we think GDP growth could moderate in the second half as domestic demand ebbs, while exports remain soft due to slowing global growth,” said Brian Lee, an economist at Maybank Securities Ltd.